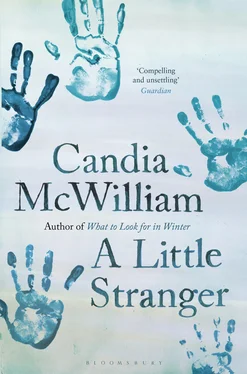

Candia McWilliam - A Little Stranger

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Candia McWilliam - A Little Stranger» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Little Stranger

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Little Stranger: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Little Stranger»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Little Stranger — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Little Stranger», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Would you like to see the nursery part of the house?’ I asked. I wanted to please her. ‘Leave your bag, it’ll be fine.’ She left it, rather reluctantly.

We went up the front stairs; the back stairs were those our child and his nanny always used. Everything was white and blue and tall. The hallways smelt of flowers and no dust. On the walls were pictures, at which she did not look. Although the child’s voice was audible, she did not follow it. I found it hard not to go to him when I heard his voice. We went on upstairs and into the room which might be hers. It looked out over fat, green fields which swelled under the July heat. The grey tower of the church showed among shimmering crowns of trees. The room was full of light and pleasantly furnished with a green-painted wooden bed, a curtained wash basin, two tables, a television, a sofa. It was decorated with a sad, pretty chintz, as though for a maiden daughter.

She came to no spoken judgement. I took her to the nursery kitchen where the nanny cooked her own food and the child’s and where other children and nannies were entertained. The smocked curtains moved at the bright window, from which the formal garden was visible, its hedges enclosing rain-clouds of grey lavender. She looked around like someone wondering whether or not to buy, and again said nothing. Sensible, really, not to be beguiled by things. After all, the child was the point. In ‘her’ sitting-room and the nursery bathroom she also passed no remark. She must perhaps be shy. Her last job had been in much the same sort of place, but perhaps I intimidated her. I am told I can. I am taller than most and have more hair. I also look at other people very hard. In the nursery bathroom, she said, ‘Where do you change?’

I could not understand the question at first. Did she think I was a werewolf?

‘Nappies,’ she explained.

‘He’s out of them,’ I said.

‘For a baby.’ She was unblushing. This really did disconcert me.

‘Do you have a baby up your sleeve?’ I asked, making light of her shawled question.

‘I am sure you will have another,’ she said, and the sense that she was accustomed to command made me leave her to her certainty, for the moment.

In John’s room, she looked around, standing in the room’s dead centre, as though the round blue nursery rug were a little pond and she a solid Grace in the middle. He played at the rim of the rug, angling for glances from me and his nanny. He had the stagey concentration of a pampered cat watching goldfish, neck bent, eyes down, nerves rehearsing real hunger. When Margaret and I came in, he and his nanny had been together on the floor; now she was in a corner of the room, folding white squares as though for a mass surrender.

John waited to hear the stranger speak.

‘Cat got your tongue?’ asked Margaret. He looked up. Her smile was all dimples and comfort. He flopped towards her on the blue, just a child again, his fair head in his hands and the bare soles of his feet waving, in the immemorial pose of a boy whose attention has been hooked.

Later, I went downstairs, leaving her to get to know the child. After a time the nanny who was about to leave came down and we sat in the kitchen. She liked black coffee too. I liked her, but she was leaving to be married, and was sorry to go, so I did not make it harder for her by talking about her departure. She was a sensible girl who made things with her hands and enjoyed masochistic sports — potholing, freefalling and such. I had even worked a little while she was with us, though I listened too much for the child.

‘What do you think?’ I asked.

‘She brought a packet of sweets for him,’ she said. ‘So he thinks she’s great.’

She is bound to be jealous, it’s a difficult time, I thought.

I said, and felt disproportionately disloyal as I did so, ‘Do you approve?’

‘Not of sweets,’ said the girl who was to depart, knowing that a part of her life was coming to an end, the important part just beginning.

Chapter 2

Margaret Pride came to live with us and to look after our child. My husband was especially pleased. ‘She’s smartly turned out,’ he said. I thought of a jelly, arriving entire on the dish from its mould, not a curve out of place, sweetly buttressed. John seemed to love her. He was an easy boy, with no temper and a desire to please. He was curious and affectionate and big for his age. He had astonishing looks which caused people to talk to whoever accompanied him in the street. He had brown eyes and white hair and he fell over often because his feet were large and he thought most of the time about private matters. He was a little timorous, and easily shamed. He did not like to be laughed at. He enjoyed bringing new words into his vocabulary, where they would be altered by his lisp and his accent, which combined the country voices of his familiars — cook, nannies, gardeners and so on — with the vowels of his parents and our friends. He also had a trick of substituting ‘f’ for ‘v’, as in ‘ferry nice’. It was as though his grandparental Dutchness was coming out. Excellent linguists, they yet trip on English ‘v’s and ‘w’s. Where the idioms are most contiguous, the Dutchman speaking English is most likely to reveal himself. Asked how many peas are in a pod, he will reply, ‘Ten, of so’ for ‘Ten, or so’. Margaret’s standard English was the off-white kind favoured by hotel receptionists and vendeuses of posh slap.

John’s fourth birthday fell in the first week of Margaret’s employment, also, coincidentally, the beginning of the grouse season. John was gun-shy so far, and I did not want to go north in Margaret’s first weeks; so he, she and I were living in the house. She did not use my Christian name. On the whole I found this an advantage.

John had spoken to his father on the telephone on the eve of his birthday. I had kissed him goodnight; his hair smelled of puppies and milky tea, sweet and smoky, the scent of toy-gun caps held in a soaped hand. Margaret was present during both John’s valedictions to his parents that evening.

She had a position for waiting, which was suggestive of the not sufficiently swift passage of time. She would turn and turn a lock of her own hair, having isolated it from the soft moss standing over her forehead, and turn her right foot over too, so its ankle, or rather leg, touched the ground. Her invariably high heel would in this way be turned inwards like a spur.

Certainly, she drove herself. The buzz of her activity filled the house. She got up early and did laundry and ironing until very late. I knew these things because I listened. Big houses carry sound as water does; the sound is clarified by the space. But she was also quite unmuffled in her activity. Her shoes tapped her presence. She behaved as though I suspected her of sneaking off for a lie-down or a cigarette, and would tell me what she had been and what she intended doing. ‘I’ve just done the ironing and I’m off to sort through the toys.’

‘Don’t take on too much,’ I had said to her. ‘Only do John’s stuff, and please tell me if anything’s not right, if anything doesn’t suit. I can’t always guess everything.’

I had not guessed anything when she surprised me in the nursery kitchen that evening. I had made him a tree, composed of sweets. The trunk was of flaky logs of chocolate, and the leaves and fruits were boiled sweets in twists of coloured paper. My idea was that he would be allowed one sweet after lunch each day until it was finished. By that time it would be autumn.

I was putting his tree beside his place at the nursery table, which Margaret had already laid for breakfast. She was good at thinking ahead. Events did not catch her out. She kept a collapsible umbrella in the back of the car. When it rained she wore a hood of transparent plastic. After the morning walk she always cleaned her gumboots. They put ours to shame. Hers were small and black and shiny. Like all her possessions, they were marked with her name, ‘M. Pride’. Such items as her hairbrush, difficult to label, she had identified with pink nail varnish, ‘M. P.’. She favoured babyish objects of adult necessity: a vanity case with a teddy bear upon it, an electric toothbrush in the shape of a chipmunk, bedroom slippers whose toes were the masks of mice, with grey crewel whiskers. These things were also named, although they could only have been hers.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Little Stranger»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Little Stranger» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Little Stranger» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.