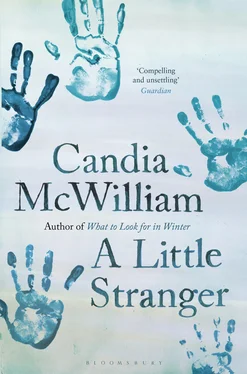

Candia McWilliam - A Little Stranger

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Candia McWilliam - A Little Stranger» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Little Stranger

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Little Stranger: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Little Stranger»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Little Stranger — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Little Stranger», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘How would you feel, looking after someone else’s kids, though? You might fancy a bit of company.’

‘And in the end they usually go and the children love us and forget them. It isn’t such a great job. You can’t get rid of your mum, short of murder. It’s not like it was for nannies.’

‘Nannies aren’t like they were. I wouldn’t want to have a devoted nympho of ninety-two living in the north wing, listening to Hard Crack on the Walkman and thinking dope fudge was interesting.’

‘They go when they’re unhappy, anyway.’

‘There must be something up with Dawn. She seems to’ve been happy with us for eight years.’

‘It’s because you let each other be but you know what goes on, I guess.’

‘I don’t draw the line very low, do you?’

They were all laughing by now, butting in. I didn’t answer Victoria’s question.

They were all fortunate in the girls they had to help them bring up their children. We all were.

‘Stealing. I s’pose. Big stealing, not just wee extras on the side of bills.’

‘Stealing my husband.’

‘Going for people with knives.’

‘Blind drunkenness on the school run, maybe.’

‘Killing one or more of the children.’

‘Alienating the affections.’

‘What’s that when it’s at home?’

‘It’s never in a proper home,’ I said.

Chapter 13

Late in March, when the game birds of the country concentrate on reproduction and revenge (chuckering asterisks of feather forcing fast cars to brake on bad corners, dying to teach their drivers a lesson), my husband was ready to leave for a fortnight in London. Even before the shooting had ended he was bored, so the sport of the season was oysters, before the town’s blossom came.

The wheat was drilled and the lambs born, the fiscal year’s end a fortnight off. I was too heavy and too tired to join him. These bouts of man’s business and men’s company transfused him. He would come back important and happy, ready again for home. John and Margaret, John and I, would go up to visit him. He missed John terribly but always said London was no place for the child. Besides, there was school, and Easter was late that year, so we could spend it all together.

I was pleased. Solomon would be safe and amused in London. I was restive and uncomfortable at night, sleepy by day, no companion for a man in spring-time. Moreover, I was by now very large. It was as though the baby was growing to enclose me, wrist for wrist, ankle for ankle.

Once you are pregnant, you have an unbreakable appointment to meet a stranger. I spent hours in a state of mental submersion, just lying or sitting; my eyes might as well have been shut. I was happiest literally submerged weightless in a warm bath. Then I felt my mind lift and play its light among the bland rotund considerations of that time. Mostly I was living off a sustaining solipsism, contemplating for hours tiny changes in my body, ribbons of silvery stretched skin on my legs and arms, blue stars of exploded capillaries, little junks and caiques of white beneath my moony nails. I watched the plundering of my own body for minerals by the miner within. I wondered, indulgently, which part of myself I would find missing next. A sense of the self has never been my strongest suit: I deemed it no dishonour that I was being dismantled.

One night, I even dreamed a person of no gender came and took my teeth, with a special tool a bit like a dibber. There was no pain, but I knew I needed my teeth for something.

Unable to sleep after that dream, though as a rule my creamiest sleep was in the early morning, I went to see John. He was not asleep either, I could hear from the pigeon-sounds from his room. He was singing and talking. He had not yet become, as he did later in the day, some sort of vehicle.

‘Good morning,’ he said, without looking up. ‘Tell me again about the scissor-man. Like last night.’

‘It’s me, John.’ I particularly disliked the scissor-man, the bladed creature who jetés across a page in Struwwelpeter , and whose vocation it is to chop off the thumbs of children who suck them. I read it in German first, so perhaps I’m not being fair; maybe I inherited something of my father’s antipathy. But even in the unGothic English script, I didn’t like it.

The most unpleasant thing, to me, are the severed stumps where the thumbs have been, which spout blood like the roses of watering cans. But we didn’t have a copy of the book in the house.

‘Hello, Mummy. Did you suck your thumb when you were young?’

‘Yes, and I’ve still got two thumbs. The scissor-man isn’t true, you know.’

‘It is so.’

‘He is not.’

‘So.’

‘Not.’

We began one of those padded tickling matches which end up on the floor. I was wrapped in my shrinking dressing-gown like a Sumo after a bout.

We were lying on the floor, out of breath. John said, ‘Pick on someone your own size. That’s what Margaret said.’

‘Isn’t Margaret bigger than you?’ I asked with sleepy pedantry.

‘She said it to the man.’

‘What man?’ I was a bit confused. John knew the names of most of the people he saw.

But he heard my interest and didn’t like the draught it let in from the grown-up world. Like his father, he had a way of cutting out when a subject had stopped being convenient. I resisted it sometimes, but that morning I thought he had as much right to be lazy, to have a time off thinking, as I had. When I had thoughts, I did not much like them.

Later, when I was dressed, I went up to the nursery to fetch John to say goodbye to his father.

‘Margaret, are you very against the sucking of thumbs?’ I was unnecessarily nervous, may even have spoonerised my question.

She looked up with surprise from John’s nape, at which she was doing up some Fair Isle buttons that were cleft like toffee-coloured beetles, and replied, ‘It’s nothing a spot of aloes can’t cure.’ She enunciated very clearly and patiently.

‘Aren’t they awfully bitter?’

‘They are known as bitter aloes.’

‘That’s undeniable.’

John raised his eyebrows at me. This adult gesture on his unlined face was funny, and he saw that I was doting on him. I felt quite warm with it. How could I ask questions about strange men, scissor-limbed or not, in front of him?

Chapter 14

He wore his cars well, my husband. In the country they were green or nicely combat-muddied milk-white, of a square and accommodating cut. For town they were sharp and slim, though long enough for evening glamour. A car once bought loses its value; among the many ways we notionally lost money, this was one of the swiftest. One of the town cars was black and the other the hardly different blue which is darker than black. It is the blue of a king’s greatcoat when he inspects his maritime forces, themselves a sea of merely navy blue.

Today he was driving himself, in the blue car. Having shut his papers in the boot, he allowed John in on his knee to say goodbye. It seemed strange, within that tank of pearly leather, tortoiseshell-walnut veneer and needled numbers, to see so much naked flesh, four unshelled limbs sticking out of shorts and a shirt, and a face without reserve, smiling beneath his father’s face.

My husband lowered the window to allow me to look through air, not glass, at his son and himself. I stood away from the car so that I might bend, seeing as I did so my wide and layered reflection, like a pile of tyres, in the sleek side of the car. Thin as the line of red alcohol in an Arctic thermometer, the stripe down the side of the car sliced my inflated reflection at the belly.

‘Look at Mummy,’ said my husband. ‘She’s got a surprise for you, Johnboy. A secret surprise.’ He paused. ‘And I’ll bring you back lots of surprises too.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Little Stranger»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Little Stranger» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Little Stranger» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.