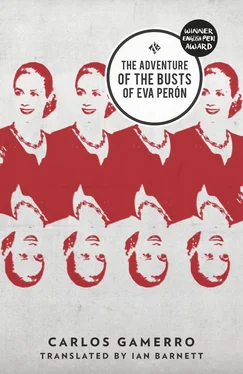

Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Carlos Gamerro's novel is a caustic and original take on Argentina's history.

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He had been wandering about among the hunched and shapeless shacks for some time now, up to his knees in mud and water, shivering in his soaking clothes, without spotting a single other human form. He plucked up the courage outside one brick house to clap hands and shout ‘ Ave María Purísima! ’, the way they do in the countryside. But no one answered his call, not even when he banged on the metal door with his open palm and shouted ‘Please, open up!’ Then, from a neighbouring shack, someone did appear: a boy in shorts of a nondescript shade, a t-shirt so short it left his distended belly exposed like some uninhibited pregnant woman’s, and blondish hair blanched more by malnutrition than by race, his legs sticking out of wellington boots so large the edges dug into his groin, but even then barely rose above the water.

‘Sweedie… is bubby in?’ Marroné asked him, and his own voice frightened him: it sounded like a toad venturing out to croak in the rain.

The boy shook his head. He was staring oddly at Marroné.

Swatting away a couple of flies that insisted on clambering over his eyelashes and lips, he tried again:

‘Aren’d dere eddy growd-ups wid you?’

As if summoned by some magic spell and preceded by the swell displaced by her body, a toothless Indian crone in a Pepsi t-shirt and men’s jeans several sizes too large appeared in the cave-mouth. She sized up Marroné with a single glance.

‘Out of here, you bum! Go and do your begging somewhere else!’ she yelled at him, before grabbing the child by the hand and disappearing into her riverside grotto.

A little further on, however, from a coloured barge beached in the mud for the rest of time, someone did answer his call.

‘Psst! Young ’un!’

A Bolivian woman in bowler hat and plaits peeked out of a porthole, shooing him away.

‘Hide yourself, young ’un,’ whished the chola. ‘They’re still snooping around.’

‘Excuse me,’ he said, without understanding properly. ‘I’m looking for El Duerdo’s house. Do you dnow hib?’

The chola shook her head, so hard her plaits cracked like whips.

‘Bibota?’

Nope.

‘Señó Gadeca? Malito? El Bebe?’

This time she switched to an emphatic nodding that left her hat tilted to one side, and a smile that revealed a gold-sheathed incisor, which for one sorry second Marroné envied, lit up her face.

‘Where cad I find deb?’

The chola’s finger pointed upwards, and Marroné’s gaze followed it, as if he hoped to see the three of them winging their way across the overcast sky. When the penny dropped, his stomach turned and he struggled to get out the question:

‘Wad happened?’

The chola made a gun of her hand and her finger pulled the trigger.

‘All thdee of dem?’

‘Señó Gareca were still a-moving. Like dis,’ she said, imitating a mermaid dancing in the waves. ‘El Bebe were me hubbie’s nephew, dead as a doorknob he was, his body tossed at de wayside. Dey was defending some big gun commandant from de guerrilla. Dey done took dem all away.’

Marroné thanked her, as a calf might thank the slaughterman that has just dealt it the hammer-blow, and staggered off through the current as best he could, past floating bits of wood, drowned rats, islands of excrement and even, face down, the corpse of a man. He had to get out of this water maze as fast as he could, away from this mock Venice of cardboard and tin. ‘I’m not from this place, this isn’t my country, there’s been a terrible mistake, help me get home,’ his head implored powerful imaginary intercessors. As in fairy tales, the babe had been stolen from his cradle and whisked through the air to a faraway land of monsters, a world that was the precisely detailed denial of all he knew and loved; he had to escape by his own native wit or he would drown and his corpse float off face down after the other one to join the rest of the trash at the foot of the steep embankment. It wasn’t so much the dying that bothered him as dying here, in this place, amidst the rubbish and the mud. He yearned to return to the golden rugby fields of his youth, feel the sun on his face, the scent of trampled clover in his lungs; if his blood had to be spilt, would that it were in a brand-new Dodds shirt, flowing red on yellow like a blazing sunset, rather than sucked from him by these sticky rags or mingling with the eddies of sewage that hemmed him in on all sides. If he could just sit down and rest for a minute, get out of the rain and his feet out of the water, regain a shred of human form, just maybe he’d be able to come up with something.

A rusty Fanta sign nailed to a wall of planks; a sheet of blue polythene propped up by two sticks that, buckling under the weight of the accumulated rainwater, formed an elegant baldachin; and a wooden bench moored with a piece of rope to prevent the current carrying it off, which came into view on peeking round the corner of one of the main channels, told him that, for once, his prayers had been answered. Relieved, he straightened the floating bench and sat down on it, his rear sinking below the waterline, and no sooner had he negotiated some kind of balance than he noticed the slant-eyed face of a man watching him from behind the bars of the window.

‘I wad somedig to drink. Somedig strog,’ ordered Marroné, stifling the urge to kiss his hands.

The man vanished into the gloom and came back with a glass of colourless liquid, but when Marroné reached out, he withdrew it into the depths. Marroné rummaged in his pocket and pulled out a huge, white, roughly square-shaped piece of limestone. Bashing it several times on one of the bars, he eventually managed to crack it and prise it open like an oyster: inside was his money, which the plaster had preserved from the ravages of the water. He daintily extracted a wad of whitish notes, still damp and stuck together, peeled one off and handed it to the man, who in return handed him the glass, the contents of which Marroné downed in one. It was cheap gut-rot, which might have been nothing more than rubbing alcohol diluted in water but, together with the tears in his eyes and the burning in his throat, he felt the warmth return to his frozen limbs, the blood to his heart and his soul to his body. He chased it down with another, which he paid for with a few coppers from the change, then, at fainting pitch, ordered a meat pasty, which promptly popped out through the bars. It was as cold and wet as a frog’s belly, but he wolfed it down without noticing. No doubt thanks to the alcohol that had burnt out his taste buds, it didn’t taste as bad as it looked, and he ordered two more, paying up front as before. He felt better with some food inside him — more upbeat, less defeated. He’d wait until nightfall and get out of there; it would be easier under cover of darkness to elude his pursuers. He told the wordless man he needed somewhere to rest for a few hours. A gesture was all it took to tell Marroné he had to enter by the back door; a few more pesos to buy him the privilege of a high bed that looked as if it was floating like a boat on the water (now he understood why they put bricks under the legs); and two minutes to undress and fall asleep under the dry blanket. He dreamt that his team had just won the rugby championship final: the captain of the rival team came up to congratulate him with a smile, his hair flaming like a beacon in the afternoon sunshine, and Marroné awoke, his eyes bathed in tears, to the sound of weeping.

The tears were his, but the weeping was coming from the next room, or maybe the next house (like dogs’ territory, boundaries here were invisible to the naked eye). He put on his barely dry clothes and, noticing with relief that the flood had retreated and left behind a memento of sedimental slime, like a lake bed, he squelched through it in his espadrilles — first inside then outside the house — in search of the source of the weeping, which seemed to coincide with a faint flickering light in a nearby window. A cool breeze was blowing and, high above, amidst the blue-grey clouds, twinkled a paltry scattering of urban stars. He pushed open a wooden door a good deal smaller than its frame, and made for a cradle improvised from a cardboard box, with tea towels for sheets, dimly lit by a lone candle set beside a picture of Eva Perón, before which stood a bunch of fresh flowers: humble daisies and honeysuckles. So their paths had crossed again; here he was, still fluttering round her flame and, for all he tried to get away, he always ended up coming back. ‘What is it now?’ he ventured to ask her. ‘What do you want from me? Why have you brought me here?’ He picked up the paint-pot-lid candlestick and brought the flame close to the face of the child within: a boy, just a few days old, a couple of weeks at most, his little almond eyes almost closed, his mouth and cheeks sticky with grime, and atop his head a crest of spiky, jet-black hair. What was such a tiny infant doing alone? What kind of people were these, how far had ignorance and poverty dehumanised them, that they could abandon such a small babe in arms? Another possibility occurred to him, and he clapped his hand to his mouth in horror. Perhaps the parents had been gunned down too. He felt, if not guilty, at least implicated, and recalled the late Sr Gareca’s lucid words, about taking responsibility for his actions, and decided to honour his last wish: he picked up the baby, cradling it to stop it crying, the way he used to with little Cynthia (only, she slept in a white wicker cradle with frills and flounces, holland sheets and satin bedspread), feeling its soft warmth against his chest. Marroné’s eyes filled with tears a second before his mind understood: the child was him; he was gazing at himself in a mirror of the past. This was how he had come into the world, this was how his life had started out: the same life in store for this child would have been his, had fate or chance not snatched him from the shack and carried him off to the palace. Not the same, he corrected himself; this child’s would be far worse, for the life of Ernesto Marroné (though, obviously, he wouldn’t have been called by that name) would have played itself out under the protection of a real-life Eva, not a mere icon like this. A series of imaginary flashbacks screened an alternative past — what his Peronist childhood would have been like under the constant care of Eva: a safe, hygienic birth in one of the brand-new hospitals that bore her name, his early years spent with his mother (his father was for now a hazy figure in this retrospective fantasy) in the spacious halls of the Maid’s Home, sleeping under satin quilts, playing with other children like himself — a Peronist child was never lonely — and drinking his milk on Louis XIV chairs upholstered in light brocade beneath chandeliers with crystal teardrops, until that ‘marvellous day’ in his mother’s life. ‘We’re going to see her, Ernestito!’ she said to him, picking him up and dancing with him (had his foster parents adopted him with that name or had they given it to him?). When the day finally came, his mother dressed him in a short-sleeved shirt, tie, short trousers and lace-up shoes, giving his slicked-down black hair a neat parting and wavy quiff; they took the tram on Avenida de Mayo and got off at Paseo Colón and Independencia, outside the imposing columns of the Foundation. Ernestito would be four or five years old. No, he couldn’t be, he realised, doing the sums; Eva would already have been dead by then. Three then, the age at which bourgeois or proletarian consciousness is born: the visit to Eva would be his earliest memory and brand his class consciousness for the rest of his days. Smiling, helpful uniformed men and women — her secretaries and assistants — would give them directions. ‘You have an audience with the Señora? This way please.’ They would walk past a long line of men in uniforms, cassocks and suits, and elegant, bejewelled women, and his mother would murmur, ‘I think these ladies and gentlemen were here first.’ ‘Them?’ Eva’s private secretary would say with a disparaging wave. ‘They are nothing but ambassadors, generals, businessmen, high-society ladies and church dignitaries. For decades they’ve gone first while the people waited. Now it’s their turn to wait. With Eva the last shall be first, and the first last,’ she concluded, pushing open the swing doors to Eva’s office.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.