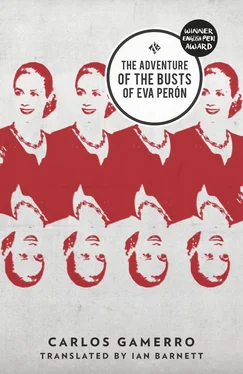

Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Carlos Gamerro's novel is a caustic and original take on Argentina's history.

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Let’s go, comrade. We don’t cry over dead combatants, we step in for them!’ the guerrilla shouted to him, and Marroné was tempted to pull rank and tell him to shut his mouth. Something had quickened inside him when he saw those bodies lying there. He’d also noticed the looks his men had been casting in his direction as much as to say ‘Do something!’ Absurdly, and quite inappropriately, the indifferent features of Tamerlán as he donned the finger-stall appeared before his eyes. All this was for that sonofabitch? No sooner had the thought crossed his mind than the jumble of emotions distilled to a clear, burning rush that rose through his chest and throat, and flooded into his tingling arms. Marroné was suddenly very angry.

‘Gimme a fucking gun!’ he shouted.

He’d barely got the words out before he had one in his outstretched palm. He recognised it immediately: a Browning 9mm. Once he reached puberty, his father would regularly take him to the Federal Firing Range, so he knew how to handle a gun and didn’t think twice as, quick as a lizard, he took a peep over the barricade, pinpointed the advancing forces taking cover behind the machines and emptied the remaining contents of the clip at them. Back on the floor, while — his hands barely trembling — he banged in a fresh clip a guerrilla had tossed to him, he realised what had happened: ‘I can do it too. I am brave after all!’ He’d tell Paddy the moment he saw him.

But for now he had other fish to fry. The man at his side gave a cry and rolled away, tiny objects were bouncing all around him as if being hurled with great force from above.

‘Snipers! Up in the roof! Let’s get out of here!’

Marroné looked up and saw what was going on. The aggressors had set the yellow chair-lifts going again and were zooming about, gunning them down like fish in a barrel. Only the enveloping smoke, especially thick up in the roof, prevented them from being picked off one by one, like olives stabbed with toothpicks. He fired a few shots upwards, but no joy as far as he could see, then dragged himself under a heavy machine to shield himself from the death raining down from the sky.

From his hiding place he watched a patrol led — or at least headed, because the real leader, a fifty-something with a face as red and meaty as raw steak and hair as white as fat, had him firmly by the arm — by a terrified Baigorria and made up of heavies carrying clubs or chains, as well as several revolvers and at least one sawn-off shotgun. ‘That one,’ Baigorria pointed suddenly with a trembling arm, and the men behind him leapt on a wounded striker dragging himself across the floor and, when they hauled him up by his hair, Marroné recognised Trejo, who was no longer wearing his white helmet, perhaps to escape detection; a ruse that, thanks to Baigorria’s untimely intervention, hadn’t worked.

‘Where’s El Colorado, the sonofabitch? Where’s El Colorado!’ they screamed at him in unison, and his reply — if he gave one — apparently didn’t satisfy them, because without asking twice they’d let go of his hair and, before he even hit the ground, they’d laid into him with sticks, chains, lengths of lead-filled hose, and knuckle-dusters, which glinted with every raised fist. One even wielded a spade.

‘This is for Babirusa, you lefty cunt!’ said the man with the white hair when they were done, and Marroné shut his eyes and covered his ears to drown out the shotgun’s thunder that finished the sentence off.

When they were at a safe distance, Marroné felt a wetness between his legs and wondered if he’d been hit. He touched it, looked at it, smelt it. It wasn’t blood; it was urine. Feeling not so much shame as detached surprise, as if it had happened to someone else, he began to drag himself towards the exit that led to the service lifts, which would allow him to get up to the offices and hide until the worst was over; he now regretted binning his James Smart suit and Italian shoes, for even in that state they would have served to identify him as one of the hostages (wasn’t he, after all?) and minimise the risk of being gunned down before getting a word in edgeways, should he have to give himself up.

But the assailants seemed to have chosen this as their meeting point, and the apse was swarming with riot police looking like armoured beetles, union thugs and security personnel. Like a praetorian guard, they rallied round the recently freed Sansimón, who, dishevelled and bald (he must have been wearing a toupee), with blackened face, torn shirt and sporting only one shoe, was screaming wildly at the top of his voice:

‘Get me Macramé! I want him dead! No! I want him alive. I want to torture him!’

There was only one thing for it. In his flight from the workshop he’d caught a glimpse of one of the huge vats brimful of fresh plaster, ready for use in the first batch of products from the newly liberated plasterworks. A team of fire-fighters was patrolling the corridors, dousing the fires with their extinguishers, and under cover of their white clouds he managed to dodge from one machine to the next and finally reached the edge of the vast pool of white. A thin crust had formed, like a crème brûlée, which Marroné broke with his boot and the thick watery paste folded itself coolly around him as he slid silently into it. He had picked up a piece of half-inch tubing on the way and, gripping it firmly in his teeth like a snorkel, he sank back in the thin gruel until he was lying flat. His plan was to stay submerged in this white mire until night fell, though exactly how he would check the light with his eyes closed under all this plaster was a riddle he hadn’t yet solved. Maybe if he counted the seconds, he could get an approximate idea of the passing of time. But he soon lost count, as keeping track of the seconds on the one hand and the minutes on the other sent his brain into a tailspin, and it was getting harder and harder to breathe too, either because the density of the liquid, far greater than water, was compressing his lungs, or because… the plaster was setting! Panic welled within him at the thought. What if, by the time he decided to get out, it was too late, and he wound up buried prematurely in a sarcophagus of calcium sulphate? The claustrophobia flooded through him in wave after wave of sheer, breathless panic, and, by raising his knees and levering himself up onto his elbows, he pressed with his forehead until he felt the fresh crust give, and, with the gingerliness of an old man extricating himself from a slippery bathtub, he lowered himself down from the vat and took two faltering steps, dripping like a pat of butter in the summer sun. Before he could take a third, he heard voices approaching. He couldn’t run in this state: he was a target with arrows pointing at him and a big sign saying ‘PLEASE SHOOT ME’. Utterly at the end of his wits he froze where he stood. He gazed blankly around the jungle of corbels, amphorae and columns, looking for anywhere to hide — and then inspiration struck. He puffed out his chest, put his hand to it, clenched the other into a fist, and raised his forehead proud and high to the future. Then he shut his eyes: if he could resist the urge to open them, there was an outside chance they would take him for a model of the Monument to the Descamisado and walk straight past.

It worked like a dream: the patrol or whoever it was he’d heard approaching walked straight past without noticing him, one of them panting the mantra ‘Motherfuckincunt! Motherfuckincunt!’, which gave Marroné no clue as to whatever or whoever it was they were looking for. He opened his eyes a crack: the coast was clear. The plaster must have set on contact with the air, which no doubt improved his camouflage; all he had to do was remain perfectly still, like one of those living statues you see in squares or in the street. Luckily, the blood had stopped dripping from his lips.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.