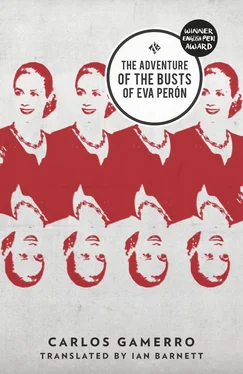

Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Carlos Gamerro's novel is a caustic and original take on Argentina's history.

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Seizing the opportunity of Marroné’s pause for effect, the young sculptor raised his hand.

‘The other one’s made of marble.’

‘Exactly!’ exclaimed Marroné, pointing at him. ‘Our comrade here knows what he’s talking about. Our comrade here couldn’t be more right. The other one is made of Carrara marble, and Michelangelo — the great Michelangelo — climbed the mountain himself to select a flawless block. But this thing…’ He spat on his palms, rubbed them together and, picking up the sledgehammer by the end of its long handle, swung it in a wide arc that ended with a sickening thud full in the great patriarch’s stomach. When the cloud of dust had cleared, through the dented mesh and fragments of plaster that hung precariously from their twisted wire threads, all could see the gaping hole Marroné had opened: the left forearm, and much of the chest and abdomen had spilt into the hollow innards of the imposing monument.

‘See? See? It’s hollow! Hollow like everything we’ve been landed with from outside. Over there they may be great works of art, comrades; here they’re nothing but empty shells. I ask you, comrades, is this the Promised Land that foreign capital is trying to sell us? A beautiful façade, yes… But what’s inside? Nothing! That’s why the General said “Neither Yankees nor Marxists — Peronists”, comrades. We don’t want anything to do with foreign ideas that later turn out to be as hollow as this dummy. You can stuff your Moseses, your Davids, your Venuses de Milo, your Eiffel Towers! They want to sell us a French pig in an Argentinian poke, comrades! Let’s stick with what’s ours for once! But what is ours, comrades? You don’t need me to tell you; even little children know that, comrades! The Martín Fierro , the Obelisk, Gardel, Perón and the Difunta Correa! And most of all Evita, the First Worker of our Argentina and the Eternal Guardian of the Revolution, comrades!’ The last few phrases he had to yell till he was hoarse to make himself heard above the noise of two hundred roaring mouths. He’d done it. He’d won. The day was his.

‘Smash ’em to bits! Destroy the foreign casts!’ shouted several enthusiasts, as if they were carrying lighted torches.

Time to channel all that energy.

‘Comrades! Comrades! Where are you going? Can’t you see the green hat? I haven’t told you about my new idea yet.’

Several people laughed. It’s true! The idea! The green-hat idea!

‘I propose that this new plasterworks — this liberated plasterworks — should be renamed the “Eva Perón Plasterworks” in honour of our Queen of Labour. And to celebrate, the first thing that should come out of its workshop today, yes, today is a consignment of ninety-two busts of Eva Perón. So, just like the days of the Foundation, when our Good Fairy was with us, the first profits will go straight into the pockets of the workers as a gift from Eva Perón. The days when the bloodsuckers kept the biggest slice of the pie are over. On behalf of Tamerlán & Sons I guarantee immediate payment here and now.’

After the lap of honour, with the workers carrying Marroné on their shoulders round the whole perimeter of the factory, they set him back on the stage, beside the battered Moses, and marched in orderly fashion towards the workshop to finish their task. Hands on hips, Marroné looked on with satisfaction. And Paddy, who had climbed up onto the platform after the celebrations, looking from him to the gaping Moses, and back, was almost lost for words:

‘Forgive me, Ernesto. I thought… Never in my life have I seen an assembly turned around like that. You’re a born cadre,’ he said with an embarrassed grin. ‘And there’s me explaining the difference to you between subjective and objective conditions, and you looking like butter wouldn’t melt in your mouth…’ No one was close enough to overhear, yet Paddy lowered his voice to a whisper. ‘You’re a mole, aren’t you? Who are you with? The ERP or us?’

‘Look…’ began Marroné reluctantly.

‘I know, I know, don’t say a word,’ he said, zipping his lips. ‘There’s just one thing I’d like you to tell me, as long as it doesn’t get you into trouble. Where did you get your training? Have you been to Cuba?’

‘Eh? No, no,’ answered Marroné, whose attention had suddenly detached itself from what was going on around him, as if obeying some inner call.

‘Something the matter?’ asked Paddy, seeing him so rapt in thought.

‘No. Yes,’ he answered as a faint smile crept across his face in response to the rare miracle about to repeat itself for the second time in a week. Something in his life was changing, no doubt about it. And, as if to himself, though not so softly that his friend couldn’t hear, he said, ‘How odd. I have this sudden urge to visit the toilet.’

6. The Sansimonazo

News of the expropriation of the Eva Perón Plasterworks (formerly the Sansimón Plasterworks) by its workers spread through the neighbourhood and local factories like wildfire, and very soon went nationwide on radio and television, which pitched the story under the sensationalist banner ‘ARGENTINE SOVIET ERA DAWNS’. So no one was surprised when the number of men and vehicles in the police guard surrounding the premises doubled, and any workers not on Eva production were consigned by their white-helmeted comrades — which now, of course, included ‘El Negro’ Ernesto — to beef up the military supplies and defence divisions. When he wasn’t lingering in dewy-eyed contemplation over the moist Evas accumulating on the drying racks, he would don the brown helmet and assist in the gathering or production of items for the defences: filling bottles with ball bearings and marbles, learning to manufacture caltrops and Molotov cocktails, rolling barrels of fuel or paint stripper to the factory’s entrances, confiscating all the pepper supplies from the kitchen or scrounging reserves from neighbouring grocers, inspecting the fire-extinguishers and fire-hoses, which one very hot day he and his comrades ended up turning on themselves, knocking each other over in rowdy cowboy duels, tripping each other up with jets of water as hard as iron bars, in an impromptu carnival romp from which they emerged grinning and drenched.

The episode perfectly encapsulated the general atmosphere that reigned in the liberated factory: they all knew an attempt to take back the Eva Perón Plasterworks was on the cards, but no one believed it was imminent. There were too many of them for one thing, and to a man they were ready to fight to the bitter end in order to defend it. The barrels of fuel and paint stripper stockpiled at the four entrances had been put on display as a gesture for the benefit of the presiding judge, just to let him know that, were the police to attack, they would at best recapture a pile of smoking ruins. And then there were the hostages. It wasn’t that the workers meant them any harm, but in the event of an attack they might be tempted to use them as human shields — and who would thank the government for recovering the factory if the owner and its chief executives had to attend the reopening in body bags? The strikers also had the people behind them, as demonstrated by the support of the locals, who cheered them every time they set foot in the neighbourhood, often lavishing provisions on them and waving the strikers away when they offered to pay with what little money they had, and generally egging them on (it was a humble neighbourhood, practically a shanty town in parts). Statements of support kept pouring in from neighbouring factories; student associations and political parties; improvising orators, of whom there was never a shortage at the gate, spoke of the Eva Perón Plasterworks as the vanguard of the proletariat and the spearhead of the Revolution. And as if that weren’t enough, Marroné had been going with unprecedented regularity since the day of the assembly. Something of the reigning euphoria must have infected him when he spoke with Govianus the accountant on the phone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.