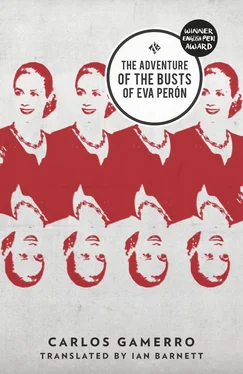

Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Gamerro - The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Carlos Gamerro's novel is a caustic and original take on Argentina's history.

The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But how? Whatever the answer, he knew that for the moment he had to watch and wait and listen. It — the answer — would come, as it had on so many other occasions, apparently out of nowhere, but a nowhere fertilised and cultivated with days or weeks of apparently fruitless effort. The bust of Eva was an oracle, a talking head that would give all the right answers when asked the right questions. And all Marroné’s questions boiled down to one basic one: would he be a condor or a sparrow? A Don Quixote or a priest and barber? A ‘man of genius’ or an ‘ordinary man’? Tomorrow maybe, or in the days to come, he was sure to find out, but he could already feel the answer incubating in the depths of his soul.

5. Seven Debating Hats

The day after the storm dawned crisp and sunny, with a brisk southerly breeze that had blown all the clouds from the sky. Its coating of plaster now removed by the rain, the skin of the landscape had emerged tender and soft as a newborn babe’s, and the lawn, plants and trees gleamed with a green that hurt the eyes, as if every leaf and every bud were seeing the light for the very first time; the luxuriant ash trees cast green pools of shade for those in need of rest, the poplars flashed their silver coins and the plumes of pampas grass waved like sails straining for the open sea. The cloudless sky that sparkled radiant as sapphire, the clean air that filled his lungs, the singing of numerous birds whose whistling and trilling in the silence of the machines cheered the very air, and the happy faces of the workers diligently coming and going about their strikers’ duties made Marroné believe at times that a new world had been born; that day and the ones to come might have been counted among the happiest he had ever known.

The work duties were rotated so that no one would feel bored or hard done by, the simplest tasks alternating with the hardest; that way, Paddy explained to him, they could also try out the order of the future society, where, as Marx had predicted, every man could develop in the area best suited to him: he could hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, and hone his critical faculties after dinner. Gradually Marroné settled into his new life. He threw himself with enthusiasm into the varied tasks, which he sometimes chose himself and sometimes was assigned, and each of which was designated by a different-coloured hard-hat: in his green hat he unloaded supplies from the delivery trucks, a task to which his rugby-player’s physique was amply suited; in the red hat he introduced improvements in canteen management, varying the dishes on the menu and above all teaching the impromptu cooks the art of seasoning, about which they knew next to nothing; and, many a night he would don the black hat for guard duty, joining in with the songs around the bonfire, learning the words as he went, swapping dirty jokes and juicy anecdotes, which he often made up off the top of his head; he would talk football or politics, tweaking his language and views to his companions’ abilities, which often turned out to be more sophisticated than he’d thought; and sometimes, his gaze lost in the crackling flames of the bonfire as it slowly collapsed into a heap of embers, he would ruminate on the turn his life seemed to be taking. A couple of times he sallied forth, sporting the blue hat of the propagandists, to hand out leaflets in the neighbourhood, always in groups of three or more, and escorted by an armed guard of black helmets; rather than fear the police, who were content for now merely to strain at the leash, their concern was that they would cross swords with the union thugs or the parapolice squads, both of which in the last few weeks had kidnapped and murdered several worker delegates. But all the same the people came out to hug them and slap them on the back as they went by, shouting things like ‘Hang on in there, lads’ or ‘Don’t let up, comrades’; housewives came out on the pavement with glasses of pop or jugs of fresh lemonade, handed out fruit or alfajores and packets of milanesa sandwiches ‘For the lads on the inside’, and Marroné now began to understand — because sometimes to understand something it isn’t enough to read about it; you have to live and breathe it — what Eva must have felt daily in her office at the Foundation, constantly in the streets and roads of her country, and overwhelmingly from the balcony of the presidential palace: the soul of the people, the beat of its heart. It was a new reality, one that neither St Andrew’s nor Stanford had prepared him for. So it was with redoubled enthusiasm that Marroné donned the yellow hat for cleaning duties, which he performed if not with gusto, then conscientiously and with dedication, and it was with an identical attitude that, donning the brown hat of the supply brigades, he spent many an afternoon collecting nuts and bolts as ammunition for catapults, or bringing office furniture down in the service lift to build barricades in anticipation of the police attack, which might come any minute. Only the leaders’ white hats were off-limits to him for now: that office bore greater responsibility and was only renewed by assembly.

The permanent mood of cooperation, which turned every chore into a joy; the presence of Paddy Donovan, on the go around the clock, lending a hand in every activity (‘The leaders wear white hats because white is the sum of all the colours: the white hat is a badge not of privilege but of duty’); the predominance of manual over mental labour — labour which, frequently taking place in the open air, gave him the freedom to go bare-chested — all of this made Marroné feel he was reliving the halcyon days of the summer camp on Mascardi Lake, of which he had so many good memories. His enthusiasm, his frank and open disposition and the smile that always played over his lips quickly earned him the recognition and soon the esteem of his new comrades. He could no longer cross the grounds without them greeting him as he went past: those who knew his name — whose numbers rose daily — would shout out ‘Hey, Ernesto! Great stuff, Ernesto!’, and those who didn’t, ‘Don’t let up, comrade!’ or ‘Nice day, comrade!’, to which he invariably replied: ‘A Peronist day!’ And for the first time in his life Marroné was grateful for the olive tone of his skin, the plumpish lips, the spiky black hair, which, coupled with his new overalls, the five-day stubble and the studied carelessness of his appearance, made it easier to pass himself off as one of them. Dale Carnegie’s rules of conversation worked just as well in this world as the one they’d originally been written for, and for anything he couldn’t hide — the educated accent, a certain bourgeois set to his body — there was always an alibi in all those middle-class youngsters that had been sent to the factories to be proletarianised and join the rank and file of the working class. The first day he had had to do guard duty at the entrance was a case in point: the Canal 13 mobile unit had approached and asked him a few questions for the daily news.

‘Five days after the start of the occupation of the Sansimón Plasterworks, how do you view the situation?’

‘Well like, the occupation ’ere and ’cross the ’ole country’s still going strong, the lads ’ere are standing firm and morale’s good and we are determined to pursue our struggle whatever the cost,’ Marroné began, suddenly dropping all his aitches, and lowering the peak of his hard-hat so the camera wouldn’t give him away.

‘What news of the hostages? When do you intend to release them?’

‘Well er… we already released everyone… ’cept the management… They’s staying ’ere till they meets all our demands… Cleverer than a box of monkeys that lot are… Sr Sansimón wouldn’t listen to our demands… ignored us didn’t he… Laughed in our face he did… laughing on the other side of his now though inne eh?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Adventure of the Busts of Eva Perón» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.