Strange, how we can’t remember the heat of a day gone by or what a thing felt like — say a girl’s silk blouse or the skin of her throat and breast. Oh, a man will say readily enough, “I remember how it felt to touch her breasts. It was a summer night, and she had opened her blouse a little at the neck.” Nothing but words. He can’t summon the sensation in his fingertips when he touched her or the prickling he felt in his own skin, which may have been the heat of a summer’s night but was most likely desire — the yearning of a young man for a girl. Maybe you’ve noticed it’s the same in dreams. You can see, you can hear, but you can’t really smell, taste, touch inside them. Some can maybe, not me. Not that it matters for the story I want to tell but can’t seem to begin properly. In a story, words are sufficient to bring a thing to life.

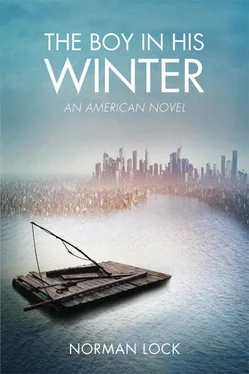

The raft. We borrowed it from Mr. Carlson, who had gone to St. Louis to buy a household slave. Looking back, I can’t say whether I had an opinion on slavery or not. Household slaves did get to bathe and wear decent clothes, something I never did in those days. Miss Watson and Judge Thatcher kept them, and they were both good Christians, if too full of starch. I wish I could say I stole Carlson’s raft to spite him for his prejudice. But I already said how Jim and I thought we were taking it for only a couple hours’ fishing. Enlightenment in the year 2077 is relatively easy — now that the white race is no longer in the majority. But in 1835, when Jim and I commenced our journey, people were rawer in their sensibilities, more indifferent in their feelings toward others. When my book is published (if it ever is), one hell of a lot of water will have gone under the bridge since I was a roughneck boy.

I wonder if I would’ve taken to Jim and treated him squarely if my father had been the owner of a cotton gin instead of the town drunk. But I’m digressing — not that I mind. I’ve always thought you could make a fine book out of nothing but digressions so long as they were scandalous. Have you read Tristram Shandy ? No? You’re missing something. I’m parched — mind getting me a cold lemonade? It’s meanness not to allow us liquor, that warm dram of consolation and dreams.

WE ENTERED A CLIMACTIC MOMENT in the Little Ice Age, below St. Louis. The raft was seized, with a noise like needles knitting, and we were hemmed in for winter — river and the old channel’s oxbow lake having frozen solid. By now, we guessed that we were not two ordinary river travelers; or if we were merely a boy and a black man, then it must have been the river that was extraordinary: a marvel that protected us by the same mysterious action that had given a common horse wings and changed a woman into a laurel tree.

You want to know if I believe in rapid adaptation — in an accelerated reorganization of atoms in order to rescue what has become suddenly indefensible.

Yes, but not as the ancients did, but as geneticists and machine neuroscientists do now. But in 2077, we have sciences and technologies unknown and undreamt of when, on a stalled raft in 1850, Jim and I shivered with cold and also with a superstitious dread. We worried about our vulnerability, now that the river no longer moved, and with it us. We were like flying insects, in danger when they are still. Could our days on the river have been like a moving picture, creating the illusion of life until a sudden stop destroys it (to use a twentieth-century figure of speech)? Of course, we aired our doubts in terms appropriate to the age. At least Jim did. As I recall, I could find no words for my uneasiness. Always the more articulate, Jim thought the magic that had kept us safe was, by the extremity of winter, overthrown.

Yes, I said magic . He believed in it, and so did I. I believe in it yet, skeptic that I am — believe in it at least a little, and a little is enough. We weren’t stupid. I may not have gone to school, but I had the native intelligence Thoreau and Emerson admired. So did Jim, who managed, like so many of us, to make room for superstition in an otherwise reasonable mind.

We were scared: Jim, because of the Fugitive Slave Act, and me, because I was in awe of the sanctity of property. Yes, even a hooligan like me. Jim was a runaway, and I was his accomplice. Not that I was above stealing, but my thefts had been of small account. The theft of a man, however, gave me pause and anxiety because of its size. Don’t we measure the significance of a thing by the space it occupies? Think of suffering: I believe the pain of a dog to be of a higher order of magnitude than that of a flea. How much greater, then, is the pain of a man? This scale of anguish produced in me a conflict when it came to Jim. On one hand, I sympathized with his misery. He was a man — I could plainly see as much. He’d been bereft of wife and children, who, according to antebellum law, were not his wife and not his children. I understood him well enough to recognize in his silences, his brooding, and in the cries he sometimes uttered in his sleep that he grieved for them. But on the other hand, Jim belonged — by law — to Miss Watson. I hated her, but she had paid good money for him. She had a bill of sale. If he’d been a dog, I’d have gone with Jim “without further ado,” as Tom Sawyer used to say. I confess I did not resolve my confusion concerning Jim’s status until long after I had left the raft for good and had begun to age as any other human inevitably does.

“I think I ought to go into the woods and hide,” said Jim after a lengthy silence in which, doubtless, he had sized up the situation.

He had good reason to vacate the raft, but I hung on to him as you will a rabbit’s foot or a cloth doll, for the sake of familiarity and luck. Jim and I’d been inseparable for — how long? From 1835 to 1850: fifteen years. We had covered relatively few river miles together, but time counts for more. Ours was not the same as now; it was the time of myth — of childhood, which is not reckoned by any clock, but by the child, who is a kind of living chronometer. Fifteen child years is an endlessly long and slow time to share so small a space with another person, no matter that few could be found in the states and territories who’d consider Jim one.

“I don’t see why you’re in such an infernal hurry to get away!” I complained.

Jim stood next to the ice-locked sweep oar, vacillating. I admit I enjoyed his distress. I knew he had to go — knew in the end he would go — but I wasn’t about to make it easy for him. I thought he should squirm some first.

“All right, Huck,” he said. “I’ll stay.”

This was the sort of unselfish gesture Jim was always making in those days, and I did not care for it. Suddenly, I saw myself wintering on the raft, a captive to the ice and to my gratitude. I would be obliged to Jim for having eased my loneliness at the risk of his own safety. It was too much, and I turned the tables on him so I might preen in my own selflessness. What else could a thirteen-year-old boy do?

“No, Jim, I want you to go. I wouldn’t want anything to happen to you.”

He smiled and thanked me for my friendship. I shook his hand and squeezed it to show I did not worry his blackness might rub off. I insisted he take some of the fatback, biscuits, apples, and rye whiskey with which we’d provisioned ourselves — years before, in Hannibal — for a day of loafing. We must see to our own needs if we’re to be better off than the sparrow. None of them had lost its goodness, a miracle of preservation proving we were under a special dispensation. Our supplies never seemed to dwindle. Whether they were constantly replenished by an invisible agency or we had no need of them, having no appetite for food, I can’t remember. But I was glad Jim took what I offered, else I might have hated him.

Читать дальше