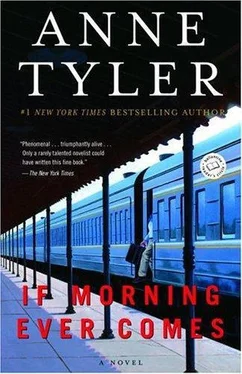

Anne Tyler - If Morning Ever Comes

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anne Tyler - If Morning Ever Comes» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:If Morning Ever Comes

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

If Morning Ever Comes: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «If Morning Ever Comes»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

HARPERS

Ben Joe Hawkes is a worrier. Raised by his mother, grandmother, and a flock of busy sisters, he's always felt the outsider. When he learns that one of his sisters has left her husband, he heads for home and back into the confusion of childhood memories and unforseen love….

If Morning Ever Comes — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «If Morning Ever Comes», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Passengers to New York and Boston take the car to the right!” the conductor sang out cheerfully. He put one hand under Shelley’s elbow to boost her up the steps. “Watch it there, lady, watch it—”

A thin white cloud of steam came out of Ben Joe’s mouth every time he breathed. Ahead of them the soldiers paused, looking over the seats in the car, and Ben Joe was left half inside and half out, with his arms rigidly close to his body to keep himself warm. He looked at the back of Shelley’s head. A few wisps of blond hair were straggling out from under her felt hat, and he couldn’t stop staring at them. They looked so real; he could see each tiny hair. In that moment he almost threw down the suitcases and turned around to run, but then the soldiers found their seats and they could go on down the aisle.

The car was full of smoke and much too hot. They maneuvered their baggage past dusty seats where all they could see of the passengers were the tops of their heads, and then toward the end the car became more empty. Shelley ducked into the first vacant seat, but Ben Joe touched her shoulder.

“Keep going,” he said. “There’re two seats facing each other at the back.”

She nodded, and got up again and continued down the aisle ahead of him. It seemed strangely silent here after the noise outside. All he could hear were the rustlings of newspapers and their own footsteps, and his voice sounded too loud in his ears.

At the last seat they stopped. Ben Joe put their luggage up on the rack, and then he took Shelley’s coat and folded it carefully and put it on top of the luggage.

“Sit down,” he told her.

She sat, obediently, and moved over to the window. When Ben Joe had put his own coat away he sat down opposite her, rubbing the backs of his hands against his knees to get them warm again.

“Are you comfortable?” he asked.

Shelley nodded. Her face had lost that strained look, and she seemed serene and unworried now. With one gloved finger she wiped the steam from the window and began staring out, watching the scattered people who stood in the lamplight outside.

“Mrs. Fogarty is seeing someone off,” she said after a minute. “You remember Mrs. Fogarty; she’s got that husband in the nursing home in Parten and every year she gives him a birthday party, with nothing but wild rice and birthday cake to eat because that’s the only two things he likes. She mustn’t of seen us. If she had she wouldn’t still be here; she’d be running off to tell—”

She stopped and turned back to him, placing the palms of her hands together. “What did your family say?” she asked.

“I didn’t tell them.”

“Well, when will you tell them?”

“I don’t know.”

She frowned. “Won’t it bother you, having to tell them we did this so sneaky-like?”

“They won’t care,” he said.

“Well. I still can’t believe we’re really going through this, somehow.”

Ben Joe stopped rubbing his hands. “You mean more than usual you can’t?” he asked.

“What?”

“You mean it’s harder to believe than it usually is?”

“I don’t follow your meaning,” she said. “It’s not usual for me to get married.”

“Well, I know, but …” He gave up and settled back in his seat again, but Shelley was still watching him puzzledly. “What I meant,” he said, “is it harder for you to believe a thing now than it was a week ago?”

“Well, no.”

He nodded, not entirely satisfied. What if marrying Shelley meant that she would end up just like him, unable to realize a thing’s happening or a moment’s passing? What if it were like a contagious disease, so that soon she would be wandering around in a daze and incapable of putting her finger on any given thing and saying, that is that? He looked over at her, frightened now. Shelley smiled at him. Her lipstick was soft and worn away, with only the outlines of her lips a bright pink still, and her lashes were white at the tips. He smiled back, and relaxed against the cushions.

“When we get there,” he said, “we’ll look for an apartment to settle down in.”

She smiled happily. “I tell you one thing,” she said. “I always have read a lot of homemaking magazines and I have picked up all kinds of advice from them. You take a piece of driftwood, for instance, and you spray it with gold-colored—”

The train started up. It gave a little jerk and then hummed slowly out of the station and into the dark, and the tiny lights of the town began flickering past the black window.

“I bought me a white dress,” Shelley was saying. “I know it’s silly but I wanted to. Do you think it’s silly?”

“No. No, I think it’s fine.”

“Even if we just go to a J.P., I wanted to wear white. And it won’t bother me about going to a J.P.…”

The Petersoll barbecue house, flashing its neon-lit, curly-tailed pig, swam across the windowpane. In its place came the drive-in movie screen, where Ava Gardner loomed so close to the camera that only her purple, smiling mouth and half-closed eyes fitted on the screen. Then she vanished too. Across from Ben Joe, in her corner between the wall and the back of her seat, Shelley yawned and closed her eyes.

“Trains always make me sleepy,” she said.

Ben Joe put his feet up on the seat beside her and leaned back, watching her face. Her skin seemed paper-thin and too white. Every now and then her blue-veined eyelids fluttered a little, not quite opening, and the corner of her mouth twitched. He watched her intently, even though his own eyes were growing heavy with the sleepy ryhthm of the train. What was she thinking, back behind the darkness of her eyelids?

Behind his own eyelids the future rolled out like a long, deep rug, as real as the past or the present ever was. He knew for a certainty the exact look of amazement on Jeremy’s face, the exact look of anxiety that would be in Shelley’s eyes when they reached New York. And the flustered wedding that would embarrass him to pieces, and the careful little apartment where Shelley would always be waiting for him, like his own little piece of Sandhill transplanted, and asking what was wrong if he acted different from the husbands in the homemaking magazines but loving him anyway, in spite of all that. And then years on top of years, with Shelley growing older and smaller, looking the way her mother had, knowing by then all his habits and all his smallest secrets and at night, when his nightmares came, waking him and crooning to him until he drifted back to sleep, away from the thin, warm arms. And they might even have a baby, a boy with round blue eyes and small, struggling feet that she would cover in the night, crooning to him too. Ben Joe would watch, as he watched tonight, keeping guard and making up for all the hurried unthinking things that he had ever done. He shifted in his seat then, frowning; what future was ever a certainty? Who knew how many other people, myriads of people that he had met and loved before, might lie beneath the surface of the single smooth-faced person he loved now?

“Ticket, please,” the conductor said.

Ben Joe handed him his ticket and then reached forward and gently took Shelley’s ticket from her purse. The conductor tore one section off each, swaying above Ben Joe.

“Won’t have to change,” he said.

Ben Joe took his suit jacket off and folded it up on the seat beside him. He put his feet back on the opposite seat and slouched down as low as he could get, with his hands across his stomach, so that he could rest without going all the way to sleep. But his eyes kept wanting to sleep; he opened them wide and shook his mind awake. Shelley turned to face the aisle, and he fastened his eyes determinedly upon her, still keeping guard. His eyes drooped shut, and his head swayed back against the seat.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «If Morning Ever Comes»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «If Morning Ever Comes» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «If Morning Ever Comes» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.