"Really?" Billy said, unperturbed. "Well, how about from the front?" From the front he was the same as ever-boyish-looking, with a high, round forehead and dazzling blue eyes. But no, if you met him on the street somewhere, wouldn't he be just another half-bald businessman? Only someone who'd known him as long as Morgan had could find the bones in his slackening face. Morgan stood blinking at him. Billy seemed first middle-aged and anonymous; then he was Bonny's high-living baby brother; then he was middle-aged again-like one of those trick pictures that alter back and forth as you shift your position. "Well?" Billy said.

"Have some champagne, why don't you?" Morgan asked him.

"No, thanks, I'll stick to scotch."

"Have some cheese, then. It's very expensive."

"Good old Morgan," Billy said, toasting him. "Good old, cheap old Morgan, right?" Morgan wandered away again. He looked for someone else to talk to, but none of the guests seemed his type. They were all so genteel and well modulated, sipping their champagne, the ladies placing their high heels carefully to avoid sinking through the sod. In fact, who here was a friend of Morgan's? He stopped and looked around him. Nobody was. They were Bonny's friends, or Amy's, or the groom's. A twin flew by-Susan, in chiffon. Her flushed, earnest face and steamy spectacles reminded him that his daughters, at least, bore some connection to him. "Sue!" he cried. But she flung back, "I'm not Sue, I'm Carol." Of course she was. He hadn't made that mistake in years. He walked on, shaking his head. Under the dogwood tree, three uncles in gray suits were holding what appeared to be a committee meeting. "No, I've been letting my cellar go, these days," one of them was saying. "Been drinking what I have on hand. To put it bluntly, I'm seventy-four years old. This June I'll be seventy-five. A while back I was pricing a case of wine and they recommended that I age it eight years. 'Good enough,' I started to say. Then I thought, 'Well, no.' It was the strangest feeling. It was the oddest moment. I said, 'No, I suppose it's not for me. Thanks anyway.'" At a gap in the hedge, Morgan slipped through. He found himself on the sidewalk, next to the brisk, noisy street, on a normal Saturday afternoon. His car was parked alongside the curb. He opened the door and climbed in. For a while he just sat there, rubbing his damp palms on the knees of his trousers. But the sun through the glass was baking him, and finally he rolled down a window, dug through his pockets for the keys, and started the engine.

These were his closest friends: Potter the musical-instrument man, the hot-dog lady, the Greek tavern-keeper on Broadway, and Kazari the rug merchant. None of them would do. For one reason or another, there wasn't a single person he could tell, "My oldest daughter's getting married. Could I sit here with you and smoke" a cigarette?" He floated farther and farther downtown, as if descending through darkening levels of water. All's Fair Pawnshop, Billiards, Waterbeds, Beer, First House of Jesus, SOUL BROTHER DO NOT BURN. Flowers were blooming in unlikely places-around a city trashcan and in the tiny, parched weed-patch beneath a row-house window. He turned a corner where a man sat on the curb flicking out the blade of his knife, slamming it shut with the heel of his hand, and flicking it out again. He traveled on. He passed Meller Street, then Merger Street. He turned down Crosswell. He parked and switched the engine off and sat looking at Crafts Unlimited.

It was months since he'd been here. The shop window was filled with Easter items now-hand-decorated eggs and stuffed rabbits, a patchwork quilt like an early spring garden. The Merediths' windows were empty, as always; you couldn't tell a thing from them. Maybe they'd moved. (They could move in a taxi, with one suitcase, after ten minutes' preparation.) He slid out of the car and walked toward the shop. He climbed the steps, pushed through the glass door, and gazed up the narrow staircase. But he didn't have what it took to continue. (What would he say? How would he explain himself?) Instead, he turned left, through a second glass door and into the crafts shop. It smelled of raw wood. A gray-haired, square-boned woman in a calico smock was arranging hand-carved animals on a table. "Hello," she said, and then she glanced up and gave him a startled look. It was the top hat, he supposed. He wished he'd worn something more appropriate. And why were there no other customers? He was all alone, conspicuous, in a roomful of quilted silence. Then he saw the puppets. "Ah, sol" he said. "Ze poppets!" Surprisingly, he seemed to have developed an accent-from what country, he couldn't say. "Zese poppets are for buying?" he asked.

"Why, yes," the woman said.

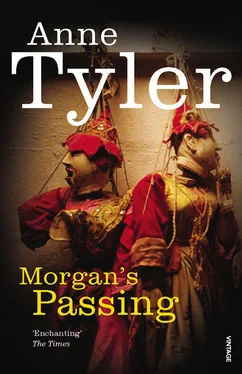

They lay on a center table: Pinocchio, a princess, a dwarf, an old lady, all far more intricate than the first ones he'd seen. Their heads were no longer round, simple, rubber-ball heads but were constructed of some padded cloth, with tiny stitches making wrinkles and bulges. The old-lady puppet, in particular, had a face so furrowed that he couldn't help running his finger across it. "Wonderful!" he said, still in his accent.

"They're sewn by a girl named Emily Meredith," the woman told him. "A remarkable craftsman, really." Morgan nodded. He felt a mixture of jealousy and happiness. "Yes, yes," he wanted to say, "don't I know her very well? Don't I know both of them? Who are you, to speak of them?" But also he wanted to hear how this woman saw them, what the rest of the world had to say about them. He waited, still holding the puppet. The woman turned back to her animals. "Perhaps I see her workroom," he said. "Pardon?"

"She leeve nearby, yes?"

"Why, yes, she lives just upstairs, but I'm not sure she-"

"Zis means a great deal to me," Morgan said. Across from him, on the other side of the table, stood a blond wooden cabinet filled with weaving. Its doors were wavery glass, and they reflected a shortened and distorted view of Morgan-a squat, bearded man in a top hat. Toulouse-Lautrec. Of course! He adjusted the hat, smiling. Everything black turned transparent, in the glass. He wore a column of rainbow-colored weaving on his head and a spade of weaving on his chin. "You see, I also am artiste," he told the woman. Definitely, his accent was a French one. She said, "Oh?"

"I am solitary man. I know no other artistes,"

"But I don't think you understand," she said. "Emily and her husband, they just give puppet shows to children, mainly. They only sell puppets when they have a few extras. They're not exactly-"

"Steel," he said, "I like to meet zem. I like you to introduce me. You know so many people! I see zat. A friend to ze artistes. What your name is, please?"

"Well… Mrs. Apple," she said. She thought a moment. "Oh, all right. I don't suppose they would mind." She called to someone at the rear, "Hannah, will you watch for customers?" Then she turned to lead Morgan out the side door.

He followed her up the staircase. There was a smell of fried onions and disinfectant. Mrs. Apple's hips looked very broad from this angle. She became, by extension, someone fascinating: she must speak to the Merediths every day, know intimately their schedules and their habits, water their plants when they went on tour. He restrained the urge to set a friendly palm on her backside. She glanced at him over her shoulder, and he gave her a reassuring smile.

At the top of the stairs she turned to the right and knocked on a tall oak door. "Emily?" she called.

But when the door opened, it was Leon who stood there. He was holding a newspaper. When he saw Morgan, he drew the paper sharply to his chest. "Dr, Morgan!" he said.

Mrs. Apple said, "Doctor?" She looked at Morgan and then at Leon. "Why," she said, "is this the doctor you told me about? The one, who delivered Gina?" Leon nodded.

Читать дальше