My mom said, "Yes, please, sand sounds lovely"

Letch said, "I could go for some sand myself."

I said, faking a British accent, "I shall return," and went out back and hopped the fence: nothing but desert for as far as I could see. It was a warm night, not too hot. There was a quail sitting in a hole near the top of a cactus. I filled my pockets with sand and jumped the fence again. I walked back to the table.

Letch said, "Waiter, may I have some sand added to my entree?"

My mom said, "Me, too, please. I'm dying for some sand."

Still using the British accent, I said, "Ladies first," and walked over to my mom and asked, "Would you like the sand on the side or on top of your burrito?"

"I'd like it right on top."

I dumped a handful on her food.

We were really cracking up. My mom laughed so hard she was crying.

"Waiter, I'm waiting," Letch said.

"Sorry, sir," and strutted over to Letch. "Fancy some sand?"

"Does the queen fancy cock?" he said, right when my mom drank more tcha-bliss, and she laughed so hard that she spit and choked.

I shook sand all over his burrito and he said, "Thank you, kind sir," and I said, "No, thank you," and my mom said, "No, we insist! Thank you," and I bowed and said, "The pleasure was mine," and strutted back to my burrito and spread the rest of the sand all over it.

We picked up our sandy burritos and pretended to eat them.

"Just when I didn't think it could get any better!" I said.

"You were right, Rhonda," Letch said. "The sand really did the trick."

My mom said, "Sand is this year's pepper."

We howled, holding our sandy burritos.

Letch smacked the table and snorted, setting his burrito down. He said, "Anyone feel like making nachos?" and my mom and I told him, yes, we'd love some nachos and we all went into the kitchen. Letch spread chips on an oven pan. I grated cheese. My mom pulled out the salsa, shook it into a bowl, and Letch said, "Oh, sure, now there's salsa," and we kept on laughing.

Her Saliva Tasted Like Blood

Me, Rhonda, with little-Rhonda, speeding up 1–5 past all those dead seals. Doing ninety: Had been roaring up the freeway since leaving Phoenix, waiting to be pulled over, but it hadn't happened yet. And it didn't happen. We made it all the way to San Francisco without a squawk from the proper authorities.

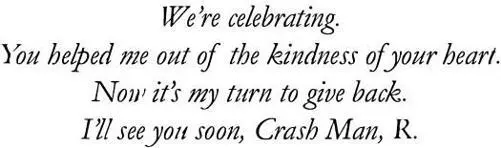

We returned the rental car and walked back to my apartment. First thing I noticed when I walked in was a present, giftwrapped in a newspaper page of stock quotes. Sitting on the burned couch. Written on its top, in a black marker, was this:

There was a small card propped against the package.

I looked at little-Rhonda and said, "You shouldn't have," and he said, "I didn't," so I opened the card:

I hadn't expected anything from old lady Rhonda.

I looked at the little guy and said, "Thanks for nothing."

He flipped me the bird. "Are you two going to have a Rhonda-vous?"

I tore into the gift, throwing the paper on the floor and opening the box. Inside, there was a receipt for an airline ticket to Burbank. For a month from now I didn't understand why anyone would want to fly to Burbank, but I figured she'd fill in the gaps later and I didn't brush my teeth or take off my shoes, just crawled in bed and passed out with the lights on, like my mom used to do. Instead of my normal nightmare, I had a dream about an old Thanksgiving dinner, from when I was a kid: the time my mom thawed frozen lasagna, saying, "Not many people know this, but some of the Pilgrims were Italian." She didn't eat any herself, but disappeared with a glass of tcha-bliss, leaving me at the kitchen table alone. I tried to cut a bite, but it was still icy in the middle.

By the next morning, my normal nightmare was back. I'll tell you about it later. Someone pounded on my door, and I got out of bed, embarrassed that I still wore the clothes decorated in dumpster-clumps. "Who's there?"

"It's me, Crash Man," old lady Rhonda said. "Open up," which I did and she stood there holding a ratty suitcase, tucking her long gray hair behind her ears. Her split lip looked much better.

I panicked that she was disappearing, too, my good hand igniting in a violent radio static, the bent, dead one waiting for a miracle. "Where are you going?"

She rubbed my cheek, flattened a few curls on my head. "I'm staying here, baby. With you." She walked over to the burned couch, set the suitcase down, told me to sit and close my eyes. I did. I heard her unzip the suitcase and she yelled, "Open up!"

The suitcase was filled with money. Small bills. Twenties, tens, fives, ones.

"Did you go on `Wheel of Fortune'?" I said.

"Not yet. But that's why we're going to Burbank. I'm on the show in five weeks."

"Congratulations. Where's the money from?"

"My husband ran off. He left me $6,000."

I was shocked: shocked that he had that kind of money and lived in this dump; shocked that he'd give any to Rhonda as he ran out of town. "Where did he go?"

"Not my problem anymore."

"Are you sad?"

"Do you want to know what we were fighting about when he hit me the other night?"

I didn't know if I really wanted to know, didn't want to hear about him being mean to her. But I loved hearing new things about old lady Rhonda so I said, "I guess."

`No. Forget it. I'm not ready to tell you."

"Why not?"

She changed the subject: "What happened on your big date?"

"Let's forget about that, too."

She laughed and said, "Fair is fair," and asked if I wanted to have dinner that night. "I've got something important to tell you.

"Great."

"You should change your outfit and take a shower before dinner," she said, laughing and holding her nose.

Being back home was really confusing, and I wish I could tell you that I did something that afternoon, that I went outside, that I looked for a job, but the truth is, I drank bourbon in bed. I stripped the sheets because I wanted to see Madeline's stain on the mattress and I rolled around, so confused about what was supposed to happen, what I was supposed to do. I'd seen my mom and watched her vanish for the last time and I'd seen Letch and burned him to the amnesty bench and I'd finally left that place for good. I was still thinking about Vern breaking my arm and Handa never wanting to see me again, and the whole world felt assaulting. I hated that people went to their jobs and shopped online. I hated that there were time zones and television stations. I hated professional sports and organic vegetables and fossil fuels. Everyone else knew how to put the bourbon down and get up off the mattress, but there was no way I could do it. I fell asleep like that. Woke up and it was dark outside.

Old lady Rhonda came in my apartment and started cooking. Two bottles of red wine sat on the small counter, uncorked. She poked her head out of the kitchen and asked if a certain sleepyhead was ready for a glass of vino.

When was the last time I'd had a glass of water?

"This is a celebratory dinner," she said, handing me my wine.

Читать дальше