David, Nkem and I would take to the floor with my brother, who, having forgotten our failures and even the mission, stamped his feet in rhythm at the staccato beat of Ras Kimono’s reggae. Mother cheered and shouted “ Onye no chie, Onye no chie ” as Obembe, my veritable brother, danced in the light. Like most people, on that day, he sought transitory relief so much that his sorrow may have sunk into the ground, allowing him in this circus of bliss. And by dawn, when the town had reclined to sleep and calm had returned to the streets and the sky was quiet and the church was empty and deserted and the fish in the river had slept and a mumbling wind riffled through the furred night and Father was asleep in the big lounge and Mother in her room with the kids, my brother stepped back out beyond the gate, and the curtain returned to its position, closing behind him. Then dawn, like an infernal broom, swept the detritus of the festival — the peace that had come with it, the relief and even the unfeigned love — like confetti scattered on a floor after the end of a party.

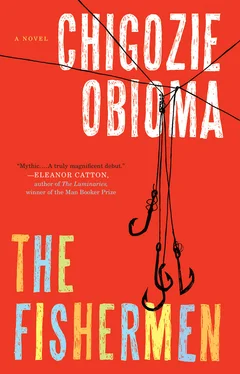

THE TADPOLE

THE TADPOLE

Hope was a tadpole:

The thing you caught and brought home with you in a can, but which, despite being kept in the right water, soon died. Father’s hope that we would grow up into many great people, his map of dreams, soon died despite how much he guarded it. My hope that my brothers would always be there, that we’d all give birth to children and have a clan, even though we nurtured it in the most primal of waters, also died. So did the hope of our immigration to Canada, just as it was close to being fulfilled.

That hope came with the New Year, bringing in a new spirit, and a peace that belied the sadness of the past year. It seemed that sadness would not return to our home. Father repainted his car a shiny navy blue and talked often, even incessantly, of Mr Bayo’s coming and of our potential immigration to Canada. He started to call us pet names again: Mother, Omalicha , the beautiful; David, Onye-Eze , the king; Nkem, Nnem , his mother. He prefixed Obembe’s name and mine with “fisherman.” Mother, too, recovered her weight. My brother was, however, untouched by this change. Nothing appealed to him. No news, no matter how small, pleased him. He was not moved by the idea of flying in an airplane or living in a city where we could ride through the streets on bicycles and skateboards like Mr Bayo’s children. When Father first announced the possibility of this, the news had come to me as big, the animal equivalent of a cow or an elephant, but to my brother, a mere ant. And when he and I went into our room later, he pinched the ant-sized promise of a better future between his fingers and threw it out of the window, and said, “I must avenge our brothers.”

But Father was determined. He woke us in the morning of January 5th — the same way he’d come into our room exactly a year before, to announce that he was moving to Yola — to announce that he was travelling to Lagos, filling me with a déjà vu. I’d heard someone say that the end of most things often bears a resemblance — even if faint — to their beginnings. This was true of us.

“I’m leaving for Lagos right now,” he announced. He wore his usual spectacles, his eyes hidden behind them, and was dressed in an old short-sleeved shirt on whose front pocket was a badge of the Central Bank of Nigeria.

“I am taking your photographs with me to apply for your travel passports. Bayo will have arrived in Nigeria by the time I return and then we will all go together to Lagos for your Canadian visa.”

Obembe and I had had our heads shaved two days before, and then followed Father to “our photographer,” Mr Little, as we called him, who operated Little-by-Little Photos. Mr Little had made us sit in soft-cushioned chairs over which was a large fabric awning with a shiny fluorescent bulb hanging above it. Behind the chairs was a white piece of cloth that covered a third of the wall. He’d flashed a blinding light, thumped his finger and asked my brother to take the seat.

Now, Father brought out two fifty-naira notes, and put them on the table. “Be careful,” he mouthed. Then turning, just like the morning he moved to Yola, he was gone.

After a breakfast of cornflakes and fried potatoes, while fetching water from the well to fill the drums, my brother announced it was time for “the final attempts.”

“We will go find him once Mama and the kids are gone,” he said.

“Where?” I asked.

“The River,” he said without turning to look at me. “To kill him like fish, with hooked fishing lines.”

I nodded.

“I have traced him two times now to the river. He seems to go there every evening.”

“He does?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said and nodded.

For the first few days of the New Year he did not talk about the mission, but brooded and stayed aloof, often sneaking out of the house especially in the evenings. He’d return and write things down in a notebook, and then make matchstick sketches of things. I did not ask him where he went at any time, and he did not tell me either.

“I have been monitoring him for some time now. He goes there every evening,” my brother said. “He goes there almost every day and bathes there, then he sits under the mango tree where we saw him. If we kill him there,” he paused as if a contradictory thought had suddenly flashed across his mind, “no one will find out.”

“When shall we go?” I mumbled, nodding.

“He goes there at sunset.”

Later, after Mother and the kids had gone and we were left alone, my brother pointed towards our bed and said: “We have the fishing lines here.”

He dragged the long staffs from under the bed. They were long barbed sticks with sickle-like hooks attached to their ends. The lines had been shortened so much that it seemed the hooks were pinned directly to the long sticks, making them unrecognizable. I knew it was my brother who had transformed this fishing equipment into a weapon. This thought froze me.

“I brought them here after I traced him to the river yesterday,” he said. “I’m now ready.”

He must have fashioned the weapons during the times he disappeared from sight without telling me. I’d become suddenly filled with fear and a pond of dark imaginations. I’d searched for him frantically all over the compound wondering, feverishly, where he was, until a stubborn thought gripped me and wouldn’t let me go. In response, I hurried to the well, breathing heavily until I prized the well’s lid open, but it fell from my hand and slammed shut as if in protest. The noise scared a bird in the tangerine tree and it leapt up with a loud call. I waited while the dust that was raised from the splintered concrete — made by the force of the closure — blew past. Then I opened the well again and peered into it. All I could see was the sun shining from behind me into the water’s top, revealing the fine sand at the bottom of it and a small plastic bucket half-buried in the clay bed beneath. I looked closely, shading my eyes until I became convinced he was not there. Then I closed the well, panting, disappointed at my own grim imagination.

The sight of the weapons made the mission real and concrete to me, as if I’d just been told about it for the first time. As my brother placed them back under the bed, I remembered all that Father had said that morning. I remembered the school we’d go to, with white people, to get the best Western education Father had always talked about as if it was a sliver of paradise which, in some way, had eluded even him. But it was abundant in Canada like leaves in a forest. I wanted to go there, and I wanted my brother to come with me. He was still talking about the river, how we were to position ourselves unseen at the banks and wait for the madman when I burst out with a cry of “No, Obe!”

Читать дальше

THE TADPOLE

THE TADPOLE