She steps into the kitchen, locks the door behind her, flips on the fluorescent ceiling light, and slides off her jeans jacket. She throws the jacket over the back of a kitchen chair, pulls open the refrigerator, and takes out an empty Gallo bottle. She drops the bottle in the trash, pulls out a beer, and twists off the cap. She squats down in front of the refrigerator and searches for the carbonara. But it’s nowhere to be found. She opens the crisper and the meat keeper, shoves aside the orange juice carton and a half dozen yogurt containers and the Tupperware that she knows is filled with a week-old, decaying salad, but there’s no pasta anywhere.

“I’m losing it,” she whispers to herself, pulls out a blueberry yogurt, then puts it back and opens the freezer. She pulls down a pint of fudge swirl gourmet ice cream, yanks off the lid, and throws it in the trash next to the wine bottle as a sign of total commitment.

She grabs a soup spoon from the drawer and goes to work, standing the whole time at the counter, leafing halfheartedly through the mail. There’s a music club offer, her Visa statement, her electric bill, a lingerie catalogue, a donation request from some cancer society, a donation request from some children’s relief society, and Mr. Bradbury’s Reader’s Digest . Since the old man died, Mrs. Acker has been giving Hannah all his magazines.

There’s also a medium-sized padded manila mailer. Hannah’s name and address are printed in black block letters in the very center of the package. There’s no return address and there’s no stamp or cancellation mark.

Hannah puts her spoon in her mouth and tears open the package. She pulls out a notebook. A common drugstore notebook, the kind a kid would take to school. It’s got a brown cardboard cover and spiral binding down the side. The cover says “Saint Ignatius” in Gothic lettering.

An odd, cold feeling starts up in her stomach. She puts the soup spoon down on the countertop and opens to the first page of the notebook. Her eyes fall on the handwriting. She immediately grabs the envelope again and turns it over, looking for something more. But there’s nothing beyond her name and address. No markings. No sign of origin.

She looks back to the words printed on the first page and there’s no way to deny the fact that this is Lenore Thomas’s notebook. The writing is smaller than normal for Lenore, but it’s unmistakable — the abundance of ink, the rigidity of angles on certain letters, the deep imprint that results from too much pressure exerted on the nub of the pen.

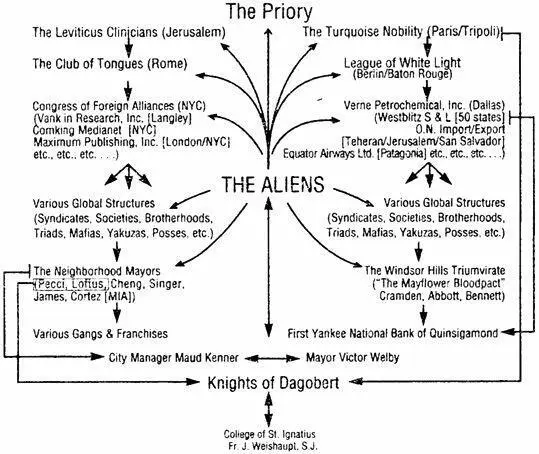

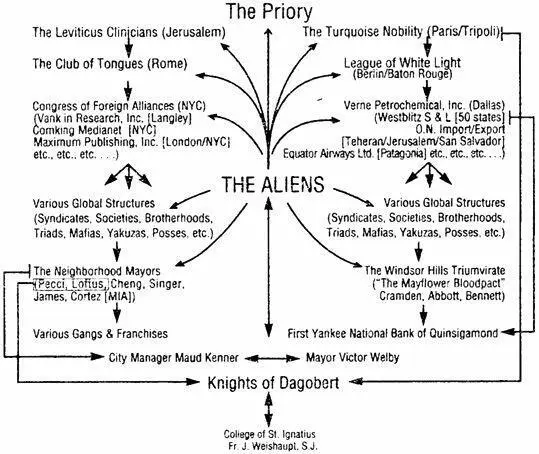

Hannah lets her thumb fan through a run of pages. Lenore has crammed as much writing as possible into the notebook. And not just writing. There are lists of unattached words, crude graphs, even a rough sketch or two. And hundreds of arrows pointing from one passage — or proper name or dollar amount or quotation — to another. It’s like the nighttime jottings of an obsessive scientist plagued by a difficult theory. Or the diary of a half-mad monk looking for an absolute proof of the Divine. Or the work journal of a drug-whacked poet plotting a unified field theory in the gorgeous words of a newly invented language.

She opens randomly to some middle page and sees a whirlpool of words, written and printed in a slightly circular pattern, tied together only by the arrow marks Lenore has drawn between them. Some of the words Hannah understands. Others she instinctively doesn’t want to. But the look of the page holds her, and it occurs to her that, maybe, rather than read the page normally, she’d have better luck deciphering it by viewing it as a picture.

Hannah flips to the last page and sees that Lenore has written End of Notebook One .

Meaning, Hannah muses, there must be more to come.

But goddamn it, Lenore, I don’t want any more. I want you to leave me alone. I don’t want your mannerisms and I don’t want your gestures and I don’t want your attitudes. And I don’t want your voice. I do not want your voice. But it keeps happening. It started out innocently. I’d be down Bangkok and I’d be scared and I’d try to think of exactly how you’d move and exactly what you’d say. And it got easier and easier. And it got results. But now it’s like I have this parasite inside of me. Feeding off of me. And it’s growing and I’m getting smaller. I don’t want to be your ghost, Lenore. Leave me alone, Lenore. I don’t want your voice. I don’t .

She closes the notebook, then opens it again near the rear, just pages from the end. She runs her hand over the writing. There’s a slight skim-coat of some kind of grainy dust, as if the notebook had been dropped on a beach of red sand.

She brushes the dust away and it sticks to her palm. She brings her palm to her nose, smells nothing, brings it to her mouth, and licks at her skin, then, without thinking, she takes the notebook under her arm and walks into her bedroom. Without putting on a light, she goes to her closet, opens the door, reaches up to a high shelf, and pulls down a brown gunmetal strongbox. She reaches into her pants pocket and takes out a key, turns the lock, and opens the box. She reaches behind to her belt holster, draws out her Magnum, and places it inside. Then she slides Lenore’s notebook underneath the gun, relocks the box, and puts it back on the closet shelf.

She stands for a second before the closet door. Then she moves to her bureau and looks at herself in the mirror. She leans in, pulls down the skin at the corners of her eyes, and mutters, “I’ve got to get more sleep.”

She turns on the digital clock radio on the bureau and the room fills up with music, an old tune that used to be a favorite of Lenore’s. She sticks her tongue out to her mirror image and tries to inspect it as Warren Zevon sings:

… in walks the village idiot

and his face is all aglow

he’s been up all night listening to

Mohammed’s radio …

She places a hand over her mouth and when she swallows, there’s an ache all the way down her throat. She remembers she’s out of aspirin, then she starts back toward the kitchen, hoping there’s another bottle of wine in the cabinet. And trying to ignore the feeling that’s already started to grow in her stomach.

WQSG is running a 7 A.M. traffic update — advice on how to maneuver around a three-car pileup at the Hoffman Square Rotary — when they’re hit. First there’s the three standard bursts of static followed by the signature trumpet blast. It could be a loop from an old Sphere bootleg. The rumor down the Canal Zone is that the brothers are fans.

Then QSG is history and O’ZBON comes alive.

Aloha. Shalom. Buenos días . And sorry for the interruption, but the only traffic problems you need worry about are the locations of the roadblocks between truth and deception, the blockades between illusion and reality, the police horses separating belonging from isolation. And that’s what we’re here for.

Brother John speaks the gospel truth, friends. I want to start off the day by grabbing the broadcast bull by his antennae-horns, as it were. Juan and I have heard down the pipe that there’s some dispute going ’round as to the authenticity of these transmissions. I had a feeling this might happen. If mon frère cares to remember, I mentioned just such a possibility during our sojourn up and down Route 66 a couple years back, during the St. Ti Jean Pilgrimage that my obsessive bro insisted upon. I think we were in Denver, trying to catch a little overdue Z-time in a trailer parked down on Laramie Street. It was hot and we’d chugged way too much joe from the endless thermos and came to review the fond memories of our breakthrough days back in the old hometown. My question was, should the heat ever back down to temperate and we cruise northeast like some mutant Irish salmon, would the apostles embrace us all over again? Or would it be rerun season and we end up stuck in that episode of Post-Easter Blues with special guest star Doubting Thomas? Well, Johnny-boy puts down his muchthumbed copy of Flashes of Moriarty to castigate yours truly over blaspheming the faithful. He says that if we headed back to the Q-town hills, within forty-eight hours word’d be blasting through the Canal Zone that the brothers were back in town and Radio Free Subterranea was about to queue up. I let the issue lie and dipped back into an old P. A. Taylor mystery. But lo and behold, a few years roll by, we slide from the headlines, the FCC turns its worry beads on the morning drivetime shock-jocks, and the coast starts to look clear for a homecoming. We make some arrangements, alert kin, and prepare security. And start the long haul out of May-he-ko — that’s right, who guessed correctly? — and make the Quinsigamond borders by the end of last month. It takes a week to retool and upgrade the old equipment, but finally we make the big comeback broadcast.

Читать дальше