‘I said I’m surprised there’s no one else around.’

‘Yes.’

I nodded. Behind her I could see a red armchair that someone had recently dragged on to the roof.

‘You live here?’ I called. She nodded.

‘You too?’

‘Yeah. I’ve seen you around, I think.’

I smiled. She bent over the railing and looked down into the street then pulled her head back so that the sun touched her throat. She looked back, a sparkle of light bouncing off her dark glasses.

‘What are you reading?’ she said.

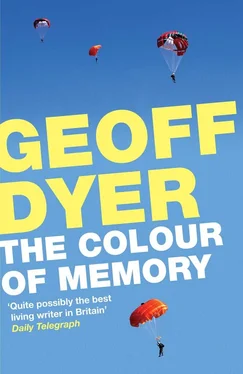

I held up the book. She leaned forward a little, raised her glasses and squinted into the sun.

‘I can’t see,’ she said, leaving the glasses perched up on her forehead.

‘You’re too far away. Maybe you should come over, then you could see it better,’ I said, grinning widely. She was smiling too, but not as much as I was.

‘Couldn’t you just tell me?’

‘It’s one of those books you really need to look at closely.’ Again I had a smile the size of a slice of melon.

‘Is it?’ she said, laughing.

‘Yeah, ideally while drinking a cold beer. .’

‘Cold beer?’

‘Like ice.’

She paused for a moment, smiling and looking around the sky.

‘It’s a great book,’ I said. She looked back, smiling and nodding.

‘Well. .’ She tapped her fingers along the railing and then added: ‘I’ll be about five minutes.’

‘Fine.’ She paused for a few seconds then turned and headed towards the stairs.

‘Hey!’ I shouted as she was about to open the door to the stairs. ‘Don’t forget the beers!’

Her laugh floated across the street invisibly.

‘Don’t push your luck.’

A little while later I saw her walk out from her block into the street.

I heard her feet on the steps and then she appeared from behind the door. She held her hand up against the glare, trapping a blue triangle of sky in the crook of her arm. She was wearing pale trousers rolled up above her ankles which were thin and tanned. A red sweater was draped around her shoulders. Draped around that was the sky.

Her name was Monica and I was sure I recognised her from somewhere. For a few moments we stood awkwardly and tried to work out where we might have met before. I handed her the Calvino, open at the passage I’d been reading, and went down to get some beer.

If you choose to believe me, good. Now I will tell how Octavia, the spiderweb city, is made. There is a precipice between two steep mountains: the city is over the void, bound to the two crests with ropes and chains and catwalks. You walk on the little wooden ties, careful not to set your foot in the open spaces, or you cling to the hempen strands. Below there is nothing for hundreds and hundreds of feet: a few clouds glide past; farther down you can glimpse the chasm’s bed.

This is the foundation of the city: a net which serves as passage and as support. All the rest, instead of rising up, is hung below: rope-ladders, hammocks, houses made like sacks, clothes-hangers, terraces like gondolas, skins of water, gas jets, spits, baskets on strings, dumbwaiters, showers, trapezes and rings for children’s games, cable cars, chandeliers, pots with trailing plants.

Suspended over the abyss, the life of Octavia’s inhabitants is less uncertain than in other cities. They know the net will last only so long.

‘Would you like to live there?’ asked Monica when I came back with the beer.

‘Where?’

‘Octavia: the spiderweb city.’

‘It would depend on what the licensing laws were like. What about you?’

‘It would depend on the weather.’

‘I don’t know where I’d like to live,’ I said. ‘I prefer to think of all the places I wouldn’t like to live and then work my way upwards.’

Evening sounds were all around us: birds, church bells, dogs barking, not much traffic. A vapour trail thin as cotton chalked itself across the sky, the plane so high that it was hardly visible. I could smell dinners being cooked and kept thinking I could hear a Bruce Springsteen song being played on a transistor radio. Confirming this suspicion, Monica said, ‘This country is turning into America.’

‘I’d like to live in America.’

‘I thought you didn’t know where you wanted to live.’

‘I don’t. That’s why I said I’d like to live in America. America has always been a synonym for anywhere that might be better than where you are now. If you know where you want to live you say Australia.’

‘I hate America.’

‘Me too.’

‘It doesn’t matter what we think or say about America anyway. Whatever we say about America we keep buying American products and that’s all that counts,’ she said, sipping a can of Budweiser.

‘I’d like to live in a place where you could walk everywhere,’ I said. ‘A city where it was warm all night and you could walk down narrow streets, past people of all ages and all races, where there were lots of jazz clubs and cheap beer.’ This sounded less impressive than I had hoped. I was tempted to suggest we got stoned. Instead I asked how long she’d lived in Brixton.

‘Three years.’

‘In the same block?’

‘No I’ve only just moved in there. Before that I was travelling.’

‘Where?’

‘India, Thailand. I went to lots of islands.’

‘Did you go scuba diving?’

‘Snorkeling.’

‘I’d like to go scuba diving more than anything else in the world.’

‘Why don’t you?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t even been skiing.’

‘Nor me.’

‘I’d love to go hang-gliding and I’ve never done that either. What was the snorkeling like? Tell me a snorkeling anecdote.’

‘As it happens I’ve got a very good snorkeling anecdote.’

‘Has it got sharks in it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Great.’

‘OK,’ said Monica after swallowing some beer. ‘One of the places I went to was a small island near Bali. On the first day there I went snorkeling. Then I found out that none of the natives ever went in the sea. Imagine that — an island people and they never go in the sea. There’s some odd convergence of currents so that sharks, octopuses, rays and stingy star-shaped things end up there. So the sea is quite dangerous but they also throw the ashes of their dead into the sea so it’s a place of evil spirits.’

‘Incredible. And this fear of the sea is a centuries-old myth, right?’

‘That’s the great thing about it. This age-old myth has only been around for twenty years,’ said Monica. ‘It’s their way of coming to an understanding of nuclear waste.’

I laughed: ‘Ah, travel. .’

‘I love it. Don’t you?’

‘It bores me rigid,’ I said.

‘Me too actually,’ said Monica. ‘Something funny always happens when I’m travelling. I go to a place to see certain things and then when I get there I suddenly don’t really care whether I actually see them or not. Just the proximity is enough. When I first went to Paris I didn’t quite see the Eiffel tower; in the Louvre I suddenly got fed up of looking for the Mona Lisa. When I was in Cairo I almost didn’t see the Pyramids.’

‘I know that feeling. When I was young my parents took my sister and me to London. We queued up for about six hours to see the treasures of Tutankhamen. We actually saw all the Tutankhamen stuff in about twenty minutes. In retrospect I think we went for the experience of queuing. In many ways it gave me my first sense of allegory.’

High up a bird — some kind of hawk — was swooning and gliding through the empty air.

We talked for a while about people we knew in Brixton. I mentioned Foomie, and Monica clapped her hand over her mouth and laughed.

‘That’s where I know you from.’

Читать дальше