I am a fish.

I am a fish.

When I fish, I fish for Bob.

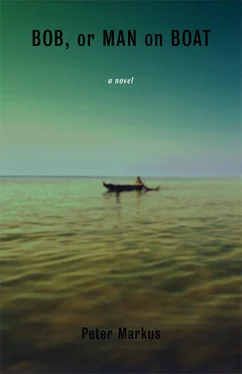

When I go out onto the river, in my boat, I am not just a fishing man.

I am a fish waiting to be caught.

The river is a bridge to Bob.

In my boat, I float and I drift and I motor on by Bob with the hope that one of these days Bob is going to look up. One of these days, when Bob looks up, he will see a light that he is looking to see.

One of these days, when Bob listens up close, he will hear a sound that he is listening to hear.

This light, this sound, it is not coming from the inside of a fish.

This light, and the song behind it, it is coming from a boat.

Not just any old boat.

It is coming from the dead man’s boat.

And I am the captain, I am the fish steering and standing in the back of this boat.

One of these days, I am going to holler out, to Bob, Bob, take a look at this fish.

I will stand with my arms spread apart as far as I can stretch them, to say to Bob that this fish that I am talking about, it is a big fish, it is a fish so big it is too big to fit inside this boat.

Will Bob even look up?

Will Bob lift up his head?

If Bob knows anything, it is this:

The fish that’s already been fished up out of the river, that fish isn’t the fish that he is fishing for.

It’s not the fish that you can see.

It’s the fish that you can’t see.

The fish that hasn’t yet been caught.

The fish that hasn’t yet been named.

When Bob reaches his hands into the river, there is no telling what he might fish up.

And then, one day, up from the river, it is the sun that rises up.

And then, like this, in the light of this light, I see the man that I call Bob.

Bob, I say, when I see that it’s him, but Bob doesn’t see me.

I am the son that Bob does not know.

I am the fish at the bottom of the river waiting to be fished up.

Bob’s boat is a magnet.

The fish in this river rise up, up to Bob’s boat, as if they are fish made out of steel.

Bob’s father liked to fish but he did not like to fish as much as Bob likes to fish.

Bob’s father was most of the time too tired from working to be able to want to fish.

When Bob’s father left the mill, after working his shift, he did not go down to the river.

To the bar, not the river, is where Bob’s father liked to go.

Bob’s father liked to drink.

Like a fish, Bob’s father, he drank.

Bob’s father liked to drink.

Like a fish.

Bob likes to fish.

Like a fish.

Bob and Bob’s father are like two fish.

They are like two fish swimming in two different rivers.

Sometimes, Bob’s father drank not just after work.

Sometimes, Bob’s father drank before work too.

Sometimes, Bob’s father even drank when he was working.

Sometimes, drinking was all that Bob’s father ever did.

And then, one day, the mill stopped making metal.

One day, the fires burning inside the mill stopped burning.

One day, the smokestacks of the mill stopped smoking with their smoke.

And from that day on, Bob’s father only had one place to go.

No, he did not go down to the river.

He’d go down to the bar.

Where he drank and drank until, one day, after drinking too much whiskey, he turned into a fish.

One night Bob’s father drank so much that when he left the bar to go home, he walked the wrong way home.

He headed down to the river.

It was dark out that night.

The moon was not anywhere in the sky shining.

Bob’s father walked down to the river in the dark.

When he got down to the river’s edge, Bob’s father, my grandfather, walked out into the river.

He did not stop walking even when the river rose up past his feet and knees.

He went on walking and walking.

He did not stop walking.

The river, it did not hold him up.

What the river did, the river, like a hungry fish, it swallowed Bob’s father up.

Bob’s father ended up, three days later, being spit back out onto the river’s other side.

The fishing man who found Bob’s father stretched out on the river’s muddy shore hoped that this man stretched out face down in the mud was only just sleeping.

But no, he wasn’t sleeping.

Bob’s father was a fish washed up dead on the river’s muddy shore.

Bob’s father’s body was brought by boat back to our side of the river.

It was then driven by ambulance into town where it ended up being taken to our town’s only undertaker.

Mr. Lynch.

Unlike many undertakers, ours did not dress in black.

Ours — Mr. Lynch — liked to wear white.

Ours was more like a clown at a birthday party than a man who took care of our town’s dead.

But it’s not like we had any choice.

Mr. Lynch was all that we had, the only one, the town’s keeper of our dead.

If you lived in our town, when you died in our town, it was to Mr. Lynch that you’d go.

Bob’s father had made it clear to Bob’s mother that when it was his time to go, he did not want to be buried.

The furnace, Bob’s father had said.

It’s how he lived, face to face with the blast furnace. And it’s how he wanted to leave.

Besides, Bob’s father had said, it’s a hell of a lot cheaper.

Take the money you’d spend on a casket and buy yourself something nice.

So Bob and Bob’s mother did what Bob’s father said.

They did not bury Bob’s father in the dirt of this earth.

They sent Bob’s father back, one last time, to the furnace.

Bob’s mother took the money they would have spent on buying a casket for Bob’s father and with this money in her hand she handed it over to Bob.

He was your father, she told him. I’ve got the house. So do like your father said, she said.

Go and buy yourself something nice.

Bob took the money from his mother’s hand.

Then Bob took from his mother’s other hand the container that contained his father’s ashes.

Where are you going with your father? his mother called out after Bob.

Bob did not say anything to this.

It was too late to get Bob to stop.

In his head, Bob was already standing at the river’s edge.

Читать дальше