“Move it, slowpoke,” Jade whispered and disappeared through the door.

Hannah’s classroom, Room 102, was located at the very end of the rootcanal hallway, a Casablanca poster taped to the door. I’d never been in her classroom before, and inside, when I opened the door, it was surprisingly bright; yellow-white floodlight from the sidewalk outside radiated through the wall of windows, X-raying the twenty-five or thirty desks and chairs and flinging long, skeletal shadows across the floor. Jade was already perched cross-legged on the stool at the front desk, one or two of the drawers hanging open. She paged intensely through a textbook.

“Find any smoking guns?” I asked.

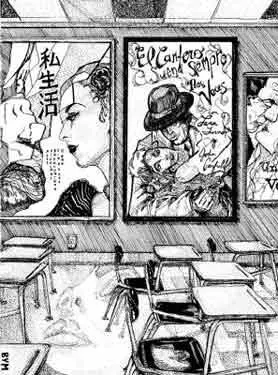

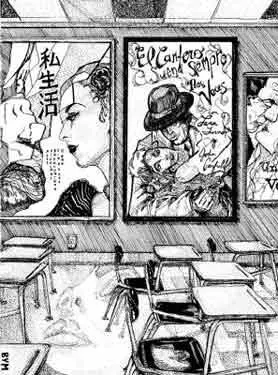

She didn’t answer, so I turned and walked down the first row of desks, staring up at the row of framed movie posters on the walls (Visual Aid 14.0).

In total, there were thirteen, including the two in the back by the bookshelf. Maybe it was because of the eggnog, but it only took a minute to realize how odd the posters were — not the fact that every one was foreign, or an American movie in Spanish, Italian or French, or even that they were each spaced some three inches apart and straight as soldiers, a level of exactitude you learned never to expect from the Visual Aids caking the walls of a classroom, not even one of Science or Mathematics. (I went up to Il Caso Thomas Crown , moved back the frame and saw, around the nail, distinct pencil lines, where she’d made the measurements, the blueprint of meticulousness.)

With the exception of two ( per un Pugno di Dollari, Fronte del Porto ), all the posters featured an embrace or kiss of some kind. Rhett was there grasping Scarlett, sure; and Fred holding onto Holly and Cat in the rain (Colazione da Tiffany) ; but there was also Ryan O’Neal Historia del Amoring with Ali MacGraw; Charlton Heston clutching Janet Leigh, making her head fall at an uncomfortable angle in La Soif du Mal; and Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr getting a great deal of sand in their bathing suits. In a funny way too, I noticed — and I didn’t think I was getting too carried away — the way the woman was positioned in each of the posters, it could very well have been Hannah embraced from there to eternity. She had their same fine china bones, their hairpin, coastal-road profiles, the hair that tripped and fell down their shoulders.

VISUAL AID 14.0

It was surprising, because she’d never struck me as the dizzy type to surround herself with firework displays of untold passion (as Dad called it, a “big to-don’t”). That she’d so meticulously assembled these Coming Attractions that had come and gone — it made me a little sad.

“Somewhere in a woman’s room there is always something, an object, a detail, that is her, wholly and unapologetically,” Dad said. “With your mother, of course, it was the butterflies. Not only could you ascertain the extreme care she took in preserving and mounting them, how much they meant to her, but each one shed a tiny yet persistent light on the complex woman she was. Take the glorious Forest Queen. It reflects your mother’s regal bearing, her fierce reverence for the natural world. The Clouded Mother of Pearl? Her maternal instinct, her understanding of moral relativism. Natasha saw the world not in blacks or whites, but as it really is — a decidedly dim landscape. The Mechanitis Mimic? She could impersonate all the greats, from Norma Shearer to Howard Keel. The insects themselves were her in many ways — glorious, heartbreakingly fragile. And so you see, considering each of these specimens, we end up with — if not your mother precisely —at the very least, a close approximation of her soul.”

I wasn’t sure why, at this moment, I thought of the butterflies, except that these posters seemed to be the details that were Hannah, “wholly and unapologetically.” Maybe Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr getting sand in their bathing suits were her ardor for living coupled with a passion for the sea, the origin of all life, and Bella di giorno featuring Catherine Deneuve with her mouth hidden was her need for shiftiness, secrets, Cottonwood.

“Oh, God,” Jade said behind me. She threw a thick paperback into the air and it fluttered, crashing against the window.

“What?”

She didn’t say anything, only pointed at the book on the floor, her breathing exaggerated. I walked over to the windows and picked it up.

It was a gray book with the photograph of a man on the front, its title in orange letters: Blackbird Singing in the Dead of Night: The Life of Charles Milles Manson (Ivys, 1985). The cover and pages were extremely tattered.

“So?” I asked.

“Don’t you know who Charles Manson is? ”

“Of course.”

“Why would she have that book?”

“A lot of people have it. It’s the definitive biography.”

I didn’t feel like going into the fact that I had the book too, that Dad included it on the syllabus for a course he’d last taught at the University of Utah at Rockwell, Seminar on Characteristics of a Political Rebel. The author, Jay Burne Ivys, an Englishman, had spent hundreds of hours interviewing assorted members of the Manson Family, which, in its heyday, included at least one hundred and twelve people, and thus the book was remarkably comprehensive in Parts II and III explaining the origins and codes of Manson’s ideology, the daily activities of the sect, the hierarchy (Part I entailed a fastidious psychoanalysis of Manson’s difficult childhood, which Dad, not being a Freud aficionado, found less effective). Dad addressed the book, juxtaposed with Miguel Nelson’s Zapata (1989), for two, sometimes three classes under the lecture title “Freedom Fighter or Fanatic?” “Fifty-nine people who encountered Charles Manson during his years living in Haight-Ashbury went on the record saying he had the most magnetic eyes and most stirring voice of any human being they’d ever encountered,” Dad boomed into the microphone at the lectern. “Fifty-nine different sources. So what was it? The It-factor. Charisma. He had it. So did Zapata. Guevara. Who else? Lucifer. You’re born with, what? That certain je ne sais quoi, and according to history, you can move, with relatively little effort, a group of ordinary people to take up guns and fight for your cause, whatever cause it is; the nature of the cause actually matters very little. If you say so — if you toss them something to believe in — they’ll murder, give their lives, call you Jesus. Sure, you laugh, but to this day, Charles Manson receives more fan mail than any other inmate in the entire U.S. penitentiary system, some sixty thousand letters per year. His CD, Lie , continues to be a mover on Amazon.com. What does that tell us? Or, let me rephrase that. What does that tell us about us? ”

“There’s no other book in here, Gag,” Jade said in a nervous voice. “Look.”

I walked over to the desk. Inside the open drawer were a pile DVDs, All the King’s Men, The Deer Hunter, La Historia Oficial , a few others, but no books.

“I found it in the back,” she said. “Hidden.”

I opened the shabby cover, flipped through a few pages. Maybe it was the stark light in the room, slashing and deboning everything, including Jade (her emaciated shadow fell to the floor, crawled toward the door), but I felt genuine chills skidding down my neck when I saw the name written in faded pencil in the upper corner of the title page. Hannah Schneider.

“It doesn’t mean anything,” I said, but noticed, with surprise, I was trying to convince myself.

Читать дальше