“Retch, you going to let anyone else look or what?”

I handed Jade the binoculars. She peered through them, gnawing her lip.

“Hope he brought Viagra,” she muttered.

Lu slouched down in her seat and froze as they climbed into Hannah’s car.

“Oh, for God’s sake, you idiot, she can’t see us,” Jade said irritably, though she, too, sat very still, waiting for the Subaru to move out of its space, sneaking behind one of the semis, before starting the car.

“Where are they going?” I asked, though I wasn’t sure I wanted to know.

“Fleabag motel,” Jade said. “She’ll bang the guy for a half-hour to forty-five minutes, then throw him out. I’m always surprised she doesn’t bite off his head like a praying mantis.”

We followed the Subaru (maintaining a polite distance) for three, maybe four miles, soon entering what I assumed was Cottonwood. It was one of those skin-and-bone towns Dad and I had driven through a million times, a town wan and malnourished; somehow it managed to survive on nothing but gas stations, motels, and McDonald’s. Big scablike parking lots scarred the sides of the road.

After fifteen minutes, Hannah switched on her blinker and turned left into a motel, the Country Style Motor Lodge, a white flat arc-shaped building sitting in the middle of a barren lot like a lost pair of dentures. A few maple trees sulked close to the road, others slouched suggestively in front of the Registration Office, as if mimicking the clientele. We pulled in thirty seconds after her, but quickly swung to the right, stopping by a gray sedan, while Hannah parked by the office and disappeared inside. Two or three minutes later, when she reappeared, slimy light from the carport splattered her face and her expression scared me. I saw it only for a few seconds (and she wasn’t exactly close) but to me, she looked like an off TV — no breathy soap opera or courtroom drama, not even a wan western rerun — just blank. She climbed back into the Subaru, started the car, and slowly pulled past us.

“Shit,” squeaked Lu, slipping down in the seat.

“Oh please, ” Jade said. “You’d be the crummiest assassin.”

The car stopped in front of one of the rooms on the far left. Doc emerged with his hands in his pockets, Hannah with a minute grin spearing her face. She unlocked the door and they disappeared inside.

“Room 22,” Jade reported from behind the binoculars. Hannah must have immediately pulled the curtains, because when a light flicked on, the drapes, the color of orange cheddar, were completely closed, without a splinter through them.

“Does she know him?” I asked. It was more a far-flung hope than an actual question.

Jade shook her head. “Nope.” She turned around in the seat, staring at me. “Charles and Milton found out about it last year. They were out one night, decided to swing by her house but then passed her car. They followed her all the way out here. She starts at Stuckey’s at 1:45. Eats. Picks one out. The first Friday of every month. It’s the one date she keeps.”

“What do you mean?”

“ You know. She’s pretty disorganized. Well, not about this.”

“And she doesn’t…know you know?”

“No way .” Her eyes pelted my face. “And don’t even think about telling her.”

“I won’t,” I said, glancing at Lu, but she didn’t seem to be listening. She sat in her seat as if strapped to an electric chair.

“So what happens now?” I asked.

“A taxi pulls up. He’ll emerge from the room with half his clothes, sometimes his shirt balled in his hands or without his socks. And then he’ll limp away in the taxi. Probably back to Stuckey’s where he’ll get into his truck, drive off to who knows where. Hannah leaves in the morning.”

“How do you know?”

“Charles usually stays the whole time.”

I didn’t especially want to ask any more questions, so the three of us lapsed into silence again, a quiet that went on even after Jade moved the car closer so we could make out the 22, the safari leaf pattern on the pulled curtains and the dent in Hannah’s car. It was strange, the wartime effect of the parking lot. We were stationed somewhere, oceans from home, afraid of things unseen. Leulah was shell-shocked, back straight as a flagpole, her eyes magnetized to the door. Jade was the senior officer, crabby, worn-out and perfectly aware nothing she said could comfort us so she only reclined her seat, turned on the radio and shoved potato chips into her mouth. I sort of Vietnamed too. I was the cowardly homesick one who ends up dying unheroically from a wound he accidently inflicts upon himself that squirts blood like a grape Capri Sun. I would’ve given my left hand to be away from this place. My Pie in the Sky was to be next to Dad again, wearing cloud flannel pajamas and grading a few of his student research papers, even the awful ones by the slacker who employed a huge bold font in order to reach Dad’s minimum requirement of twenty to twenty-five pages.

I remembered what Dad said when I was seven at the Screamfest Fantasy Circus in Choke, Indiana, after we’d taken the House of Horrors ride and I’d been so terrified I’d ridden the thing with my fingers nailed to my eyes — never peeking, never once glimpsing a single horror. After I pried my hands off my face, rather than chastising my cowardice, Dad had looked down at me and nodded thoughtfully, as if I’d just revealed startling new insights on revolutionizing welfare. “Yes,” he’d said. “Sometimes it takes more courage not to let yourself see. Sometimes knowledge is damaging — not enlightenment but enleadenment. If one recognizes the difference and prepares oneself — it is extraordinarily brave. Because when it comes to certain human miseries, the only eyewitnesses should be the pavement and maybe the trees.”

“Promise I won’t ever do this,” Lu said suddenly in a mousey voice.

“What,” said Jade in a monotone, her eyes papercuts.

“When I’m old.” Her voice was something frail you could tear right through. “Promise me I’ll be married with kids. Or famous. That…”

There wasn’t an end to her sentence. It just stopped, a grenade that’d been thrown but hadn’t exploded.

None of us said anything more, and at 4:03 A.M. someone turned off the lights in Room 22. We watched the man emerge, fully clothed (though his heels, I noticed, were not fully inside his shoes) and he drove away in the rusty Blue Bird Taxicab (1-800-BLU-BIRD), purring as it waited for him by the Registration Office.

It was just as Dad said (if he’d been in the car with us he would have tipped up his chin, just a little, raised an eyebrow, his gesture for both Never Doubt Me and I Told You So) because the only eyewitnesses should have been the neon sign shuddering VACANCY, and the thin asthmatic trees seductively trailing their branches down the spine of the roof, and the sky, a big purple bruise fading too slowly over our heads.

We drove home.

Two weeks after the night we spied on Hannah ( “Observed,” Chief Inspector Ranulph Curry clarified in The Conceit of a Unicorn [Lavelle, 1901]), Nigel found an invitation in the wastepaper basket in her den, the tiny room off the living room filled with world atlases and half-dead hanging plants barely surviving on her version of flora life support (twenty-four-hour plant lights, periodic Miracle-Gro).

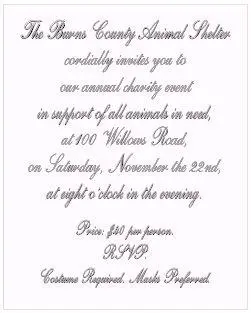

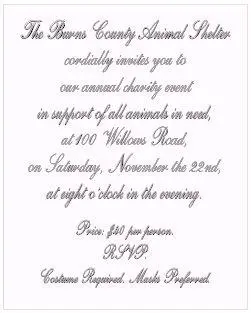

It was elegant, printed on a thick, cream, embossed card.

Читать дальше