Hannah must have sensed we were heading toward a stalemate, because shortly thereafter, she launched her next assault.

“Jade, why don’t you take Blue with you when you go to Conscience? It might be fun for her,” she said. “When are you going again?“

“Don’t know,” Jade said drearily, sprawled on her stomach on the living room carpet, reading The Norton Anthology of Poetry (Ferguson, Salter, Stallworthy, 1996 ed.).

“I thought you said you were going this week,” Hannah persisted. “Maybe they can squeeze her in?”

“Maybe,” she said without looking up.

I forgot this conversation, until that Friday, a worn, gray afternoon. After my last class, AP World History with Mr. Carlos Sandborn (who used so much gel, one always thought he’d just come from swimming laps at the Y), I returned to the third floor of Hanover to find Jade and Leulah standing by my locker: Jade, in a black Golightly dress, Leulah, a white blouse and skirt. Standing with her hands and feet together as if waiting for choir practice, Leulah looked pleasant enough, but Jade looked like a kid in a nursing home impatiently waiting for her designated fogey to be wheeled in so she could read him Watership Down in a monotone, thereby earning her Community Outreach credit, thereby graduating on time.

“So we’re going to get our hair and nails and eyebrows done and you’re coming,” Jade informed me with a hand on her hip.

“Oh,” I said, nodding, spinning through the combination of my padlock, though I don’t think I was actually entering the combination, only vigorously turning it in one direction, then the other.

“Ready?”

“Now?” I asked.

“Of course now. ”

“I can’t,” I said. “I’m busy.”

“ Busy? With what? ”

“My dad’s picking me up.” Four sophomore girls who’d drifted by had snagged, like garbage in a river, by the German Language Bulletin Board. They blatantly eavesdropped.

“Oh, God,” said Jade, “not your wonder dad again. You’ll have to let us know his civilian name and what he looks like without the mask and the cape.” (I’d made the serious mistake of bringing Dad up the previous Sunday. I think I actually said the phrase “brilliant man” in relation to him, also “one of the preeminent commentators on American culture at work in this country today,” a line lifted verbatim from the two-page spread on Dad in TAPSIM, the American Political Science Institute’s quarterly [see “Dr. Yes,” Spring 1987, Vol. XXIV, Issue 9]. I’d said it because Hannah had asked what he did for a living, how he “kept busy,” and something about Dad simply invited the boast, the brag, the self-congratulating monologue.)

“She’s just kidding,” Lu said. “Come on. It’ll be fun.”

I collected my books and walked outside with them to inform Dad my Ulysses Study Group had decided to meet for a few hours, but I’d be home for dinner. He frowned at the sight of Jade and Lu standing on the Hanover steps: “Those two tartlets think they can read Joyce? Heh. Good luck to them — let me revise that — pray for a miracle.”

I could tell he wanted to say no, but was reluctant to make a scene.

“Very well,” he said with a sigh and a pitying look. He started the Volvo. “Tallyho, my dear.”

As we walked to the Student Parking Lot, I heard his rave reviews.

“Shit,” Jade said, looking at me with surprised esteem. “Your dad’s magnifico. You said he was brilliant but I didn’t realize you meant in a Clooney way. If he wasn’t your dad, I’d ask you to set me up with him.”

“He looks like what’s his name…the father in The Sound of Music ,” said Lu.

Frankly, it could get a little stale how Dad, within minutes, could elicit such worldwide acclaim. Sure — I was the first person to stand up and throw him roses, shout, “Bravo, man, bravo!” But sometimes I couldn’t help but feel Dad was an opera diva who garnered reverential ratings even when he was too lazy to hit the high notes, forgot a costume, blinked after his own death scene; something about him seized approval from everyone, regardless of the performance. For instance, when I passed Ronin-Smith, the guidance counselor, in Hanover Hall, it seemed she’d never gotten over the minutes Dad had spent in her office. She asked not “How are your classes?” but “How’s your father, dear?” The only woman who’d met him and not inquired after him ad nauseam was Hannah Schneider.

“ Right …Mr. Von Trapp,” said Jade thoughtfully, nodding, “Yeah, I always had a thing for him. So where’s your mom in all this?”

“She’s dead,” I said in a dramatic, bleak voice, and for the first time, enjoyed their astonished silence.

They took me to purple-walled, zebra-couched Conscience, located in downtown Stockton across from the public library, where Jaire of the alligator boots (pronounced “jay-REE”) gave me copper highlights and cut my hair so it no longer looked “like she did it herself with a pair of toenail scissors.” To my surprise, Jade insisted my new grooming initiative was complimentary, care of her mother, Jefferson, who’d left Jade her black American Express card “in case of Emergency” before disappearing for six weeks in Aspen with her new “hottie,” a ski instructor “named Tanner with permanently chapped lips.”

“I’ll give you a thousand dollars if you can do something with those broom-bangs,” Jade instructed my hairdresser.

Also funded by Jefferson, over the next two weeks, was my six-month supply of disposable contact lenses procured from ophthalmologist Stephen J. Henshaw, MD, with eyes like an Arctic Fox’s and a bad head cold, as well as clothes, shoes and undergarments hand-selected for me by Jade and Lu not from the Adolescent Department of Stickley’s, but at Vanity Fair Bodiwear on Main Street, at Rouge Boutique on Elm, at Natalia’s on Cherry, even at Frederick’s of Hollywood (“If you ever decide to get kinky, I suggest this for the occasion,” Jade instructed, thrusting something at me that resembled the harness one dons before skydiving, only in pink). The final coups de grâce to my previous dull appearance were moisturizing makeups, the thyme and myrtle lip shimmers, the day (shiny) and evening (murky) eye shadows exhumed especially for my skin tone from Stickley’s cosmetics main floor, as well as the fifteen-minute application tutorial by gum-chewing Millicent with her powdery forehead and spotless lab coat. (She artfully crammed the entire white light color spectrum onto both of my eyelids.)

“You are a goddess,” Lu said, smiling at me in Millicent’s hand mirror.

“Who would’ve thought,” cracked Jade.

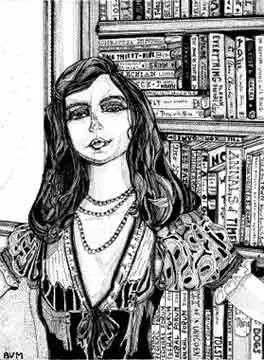

I was no longer apologetically owl-like, but impenitently pastrylike (Visual Aid 9.0).

VISUAL AID 9.0

Dad, of course, witnessing this transformation, felt the way Van Gogh would probably feel, if, one hot afternoon, he happened to wander into a Sarasota Gift Shoppe and found, next to the cardboard baseball caps and Fun-in-the-Sun seashell figurines, his beloved sunflowers printed on one side of two hundred beach towels on SALE for just $9.99.

“Your hair appears to blaze, sweet. Hair is not supposed to blaze. Fires are supposed to blaze, illuminated clock towers, lighthouses, Hell perhaps. Not human hair.”

Soon, however, rather miraculously, apart from the odd gripe or humph, most of his indignation subsided. I assumed it had to do with his absorption with Kitty, or, as she called herself on our answering machine, “Kitty Cat.” (I hadn’t met her, but had heard the latest headlines: “Kitty Swoons in Italian Restaurant Due to Dad’s Musings on Human Nature,” “Kitty Begs Dad’s Forgiveness for Spilling Her White Russian on Cuff of His Irish Tweed,” “Kitty Plans Her Fortieth Birthday and Hints at Wedding Bells.”) It was bizarre, but Dad appeared to have accepted the fact that his work of art had been shamelessly commercialized. He even seemed to harbor no ill will.

Читать дальше