I didn’t go mad. I got mad (see “Peter Finch,” Network ). Rage, not Abe Lincoln, is the Great Emancipator. It wasn’t long before I was tearing through 24 Armor Street, not limp and lost, but throwing shirts and June Bug needlepoints and library books and cardboard moving boxes marked THIS END UP like Jay Gatsby on a rampage, searching for something — even if it was something minor — to give me proof of where he’d gone and why. Not that I let myself hope I’d discover a Rosetta Stone, a twenty-page confession thoughtfully tucked into my pillowcase, between mattresses, in the icebox: “Sweet. So now you know. I am sorry, my little cloud. But allow me to explain. Why don’t we start with Mississippi…” It wasn’t likely. As Mrs. McGillicrest, that penguin-bodied shrew from Alexandria Day, had informed our class, so triumphantly: “A deus ex machina will never appear in real life so you best make other arrangements.”

The shock of Dad gone ( shock didn’t do it justice; it was astonishment, stunned, a bombshell — astunshelled), the fact he had blithely hoodwinked, bamboozled, conned (again, too tepid for my purposes — hoodzonked) me, me, me, his daughter, a person who, to quote Dr. Luke Ordinote, had “startling power and acumen,” an individual who, to quote Hannah Schneider, did not “miss a thing,” was so improbable, painful, impossible (impainible), I understood now Dad was nothing short of a madman, a genius and imposter, a cheat, a smoothie, the Most Sophisticated Sweet Talker Who Ever Lived.

Dad must be to secrets as Beethoven is to symphonies, I chanted to myself. (It was the first of a series of stark statements I’d concoct in the ensuing week. When one has been hoodzonked, one’s mind crashes, and when rebooted, reverts to unexpected, rudimentary formats, one of which was reminiscent of the mind-bending “Author Analogies” Dad devised as we toured the country.)

But Dad wasn’t Beethoven. He wasn’t even Brahms.

And Dad not being an unsurpassed maestro of mystery was regrettable, because infinitely more harrowing than being left with a series of obscure, incomprehensible Questions — which one can fill in at one’s whim without fear of being graded — was having a few disquieting Answers.

My rampage through the house uncovered no evidence of note, only articles about civil unrest in West Africa and Peter Cower’s Inside Angola (1980), which had fallen in the crevice between Dad’s bed and bedside table (as nutritionless pieces of evidence as they come) and $3,000 in cash, crisply rolled up inside June Bug Penelope Slate’s SPECIAL THOUGHTS ceramic mug kept on top of the refrigerator (Dad had purposefully left it for me, as the mug was usually reserved for loose change). Eleven days after he left, I wandered down to the road to collect the day’s mail: a book of coupons, two clothing catalogues, a credit card application for Mr. Meery von Gare with 0 % APR financing and a thick manila envelope addressed to Miss Blue van Meer, scrawled in majestic handwriting, the handwriting equivalent of trumpets and a stagecoach pulled by noble steeds.

Immediately, I ripped it open, pulling out the inch-thick stack of papers. Instead of a map of the South American White Slavery network with rescue instructions, or Dad’s unilateral Declaration of Independence (“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for a father to dissolve the paternal bands which have connected him to his daughter…”), I found a brief note on monogrammed stationery paper clipped to the front.

“You asked for these. I hope they help you,” Ada Harvey had written, then scrawled her loopy name beneath the knot of her initials.

Even though I’d hung up on her, hacked off her voice without a word of apology like a sushi chef chopping off eel heads, exactly as I’d asked, she’d sent me her father’s research. As I raced back up the driveway and into the house with the papers, I found myself crying, weird condensation tears that spontaneously appeared on my face. I sat down at the kitchen table and carefully began to page through the stack.

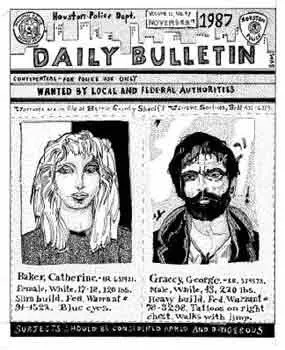

Smoke Harvey had handwriting that was a distant cousin of Dad’s, minuscule script blustered by a cruel northeasterly. THE NOCTURNAL CONSPIRACY, the man had written in caps in the top right corner of every page. The first few papers detailed the history of The Nightwatchmen, the many names and apparent methodology (I wondered where he’d gotten his information, because he referenced neither Dad’s article nor the Littleton book), followed by thirty pages or so on Gracey, most of it barely readable (Ada had used a photocopier that printed tire treads across the page): “Greek in origin, not Turkish,” “Born February 12, 1944, in Athens, mother Greek, father American,” “Reasons for radicalism unknown.” I continued on. There were photocopies of old West Virginia and Texas newspaper articles detailing the two known bombings, “Senator Killed, Peace Freaks Suspected,” “Oxico Bombing, 4 Killed, Nightwatchmen Sought,” an article from Life magazine dated December 1978, “The End of Activism,” about the dissolution of the Weather Underground, Students for a Democratic Society and other dissident political organizations, a few papers about COINTELPRO and other FBI maneuverings, a tiny California article, “Radical Sighted at Drugstore,” and then, a newsletter. It was dated November 15, 1987, Daily Bulletin , Houston Police Department, Confidential, For Police Use Only, WANTED BY LOCAL AND FEDERAL AUTHORITIES, Warrants on file at Harris County Sheriff Warrant Section, Bell 432-6329—

My heart stopped.

Staring back at me, above “Gracey, George. I.R. 329573. Male, White, 43, 220, Heavy build. Fed. Warrant #78-3298. Tattoos on right chest. Walks with limp. Subjects should be considered armed and dangerous”—was Baba au Rhum (Visual Aid 35.0).

VISUAL AID 35.0

Granted, in the police photo, Servo sported a dense steel-wool beard and mustache, both doing their best to scrub out his oval face, and the photograph (a still taken from a security camera) was in sloppy black and white. Yet Servo’s burning eyes, his lipless mouth reminiscent of the plastic gap in a Kleenex box with no Kleenex, the way his small head stood up against his bullying shoulders — it was unmistakable.

“He always hobbled,” Dad had said to me in Paris. “Even when we were at Harvard.”

I grabbed the paper, which also featured the sketch of Catherine Baker, the one I’d seen on the Internet. (“Federal Authorities and the Harris County Sheriff’s Department are asking for public assistance in obtaining information leading to the Grand Jury indictment of these persons…” it read on the second page.) I ran upstairs to my room, yanked open my desk drawers, and dug through my old homework papers and notebooks and Unit Tests, until I found the Air France boarding passes, some Ritz stationery, and then, the small piece of graph paper on which Dad had scribbled Servo’s home and mobile telephone numbers the day they’d left me and gone to La Sorbonne.

After some confusion — country codes, reversing ones and zeros — I managed to correctly dial the mobile number. Instantly, I was met with the hisses and heckling of a number no longer in service. When I called the home number, after a great deal of “Como?” and “Qué?” a patient Spanish woman informed me that the apartment wasn’t a private residence, no, it was available for weeklong lettings via Go Chateaux, Inc. She pointed me toward the vacation Web site and an 800-number (see “ILE-297,” www.gochateaux.com). I called the Reservations line and was curtly told by a man that the apartment hadn’t been a private residence since the company’s inception in 1981. I then tried to wrench free whatever info he had on the individual who’d leased the unit the week of December 26, but was informed Go Chateaux wasn’t authorized to disclose their client’s personal records.

Читать дальше