As they closed with the target, Bertinetti led the sortie in a gradual climb to 5,000 feet. A few individual ZSU-23-4s started to put up a massive barrage of manually aimed flak. So, just short of the target and conscious of the streams of Russian tracer flashing past his canopy, he had overcome his natural instinct to turn and dive to make for a more difficult target and had, instead, gritted his teeth and held his course and height before releasing his two GBU-31, Mark 84 bombs. Guided by the JDAM kits, they hit the radar station in the center of the roof with a massive explosion. Pulling left and climbing aggressively to escape the flak and join the circling F-15s, he had seen the building erupt as the two bombs buried themselves deep inside—only to be followed by the other seven F-16s, also achieving perfect hits.

Extraordinary , thought Bertinetti. Although they had not said as much, HQ had sent out his eight F-16s in the hope that one or two might get through. And one direct hit would probably have been enough to knock out the radar. Instead they had all survived and all had scored. What was really going on down there in Kaliningrad, he wondered. Because someone had been, and was still being, very clever indeed.

“Giant Killer, this is Apollo. Mission accomplished.” Bertinetti spoke coolly into his radio to ground control. “Now heading to link up with tankers before getting back on CAP.”

“Apollo, copy that. Tally ho and good hunting.”

0115 hours, Sunday, July 9, 2017, Central European Time

0215 hours, Sunday, July 9, 2017, Eastern European Time

Forest north of Pravdinsk Iskander Battery, Kaliningrad

FACE BLACKENED WITH cam cream, Captain Jack Webb, commander of the elite US Special Forces ODA team, which had just jumped in, whispered urgently to Morland. “I’m happy with the LZ preparation. It’s tight, but workable. I’m leaving two of my guys to control it from here. I now need to get up close to be ready to laser target-mark enemy positions for air strikes to allow the company to assault the compound.”

The twelve men of the Green Beret ODA team had worked fast since landing. After hitting the ground, each man had bundled up his parachute and hastened into the cover of the forest. Parachutes, oxygen masks and other kit necessary for the high-altitude jump were quickly hidden under bushes. Once they were ready, they had moved out of the forest and onto the main landing zone, all the while covered by Morland’s team and the Lithuanians as they worked.

Given the imminent arrival of the air-assault company, preparations had been rudimentary but everything took time, especially in the dark and while trying to maintain operational security by making no noise and showing no lights. The center of the LZ was marked by nine infrared Cyalume lightsticks—invisible to the naked eye—in the shape of a large letter “A,” which would easily be picked up by incoming Chinook pilots wearing night vision goggles. A similar Cyalume was placed on the trailing edge of the LZ to indicate the direction in which helicopters were to depart from the LZ. Finally, the team conducted a quick recce to confirm that there were no major obstacles on or around the LZ; a Chinook landing on some abandoned farm equipment could be fatal.

“Right, Jack, here’s how we’re going to approach the perimeter,” replied Morland, acutely conscious that the only way to maintain their luck was to keep moving with the utmost care and deliberation. He did not want to lose surprise at this late stage. Once the heliborne troops that Webb had told him would be following had landed, all hell would break loose, but right now, all was quiet and the Russians had not reacted in any way. He was praying that nothing had alerted them to the arrival of the Green Berets.

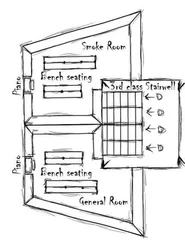

He pulled out his map and with a shaded, red-bulbed torch, showed Webb the route: three hundred meters due east through the forest, then southeast along the edge of the tree line for a kilometer and a half. They’d follow the trees around what looked like the heel of a foot at the corner of the forest, before heading due south toward a sunken lane with a scrubby hedge running along one side, around 300 meters north of the compound.

This would give them some cover from which they could observe the anti-personnel minefield, the perimeter fence, watchtowers and the Command Bunker. Although, as Morland pointed out, they would need to listen out for the sound of engines, as that would indicate the hourly roving patrol was heading out of the compound. From Morland’s previous recce, he had calculated that it would then take no longer than three minutes before the patrol, if it turned in that direction, would be heading down the lane. And if they were caught in the sunken lane, it would be game over.

Webb took it all in and indicated that he was content with a brief thumbs up. Then, in a whisper, Morland outlined the drills so that Webb could brief his men before they set out. They would move in three groups, maintaining enough distance between each to provide mutual support in case one was hit. Archer and Watson would form the gun group and would move first through the forest, taking up a fire position with the GPMG and night vision goggles on the eastern side. They would then cover the scout group, with Lukša leading and consisting of Webb, his ODA engineer sergeant, Morland, Krauja and Bradley. Once the scouts had started their move down the outside of the forest, the reserve group, made up of Sergeant Wild, the two Lithuanians and the remaining eight men of the ODA team, would traverse the forest and wait on the edge of the tree line, ready to guide the reinforced company forward for its assault on the compound, or to be called forward to assist if required.

“That’s the plan. But tell your guys to stay flexible. It all depends on how we find the ground. We haven’t been near the wire, for obvious reasons, only observed it from a distance. The enemy seem stuck into a pretty fixed routine, but who knows what they’ll do when they hear our helicopters.”

“Sure, Tom. Give me ten.” And Webb crept back to brief his ODA on the plan.

Shortly afterward, after a whispered “good to go” from Webb and a thumbs up from Morland, the shadowy figures of Archer and Watson moved off into the forest. A brief shaft of moonlight through the clouds glinted on the belts of ammunition they had draped off their shoulders, giving them the appearance of Mexican bandits. But there was no affectation about it. They would be cursing the extra weight and the risk of snagging the linked rounds on branches as they moved through the trees. However, they all knew that if something went wrong, the GPMG would burn through ammunition at an alarming rate. That was why the rest of the team, him included, were all carrying an extra belt of 200 rounds, “just in case.”

After ten minutes, a whispered message in the earpiece of the personal role radio, given to him by the Latvian Forest Brothers, told him that the gun group were in position and ready.

Wordlessly Lukša followed with the rest of the scout group. Fifteen minutes later, they were through the forest and moving southeast along the eastern edge of the tree line. Morland felt a faint breeze bringing the scent of newly cut hay from a distant field. The moon was still low in the sky, its silver light, thankfully, still mostly obscured by clouds.

Then Lukša stopped and pointed ahead to Archer on the gun and Watson lying beside him, ready to feed in the belt of ammo now stacked in a neat pile to the left of the gun on a poncho, to stop the ammunition getting dirty. Perfect, but Morland would have expected no less from these two.

They took up positions in all-round defense. Morland tapped Watson on the shoulder and he tapped Archer. The gun group, carefully and quietly and making no effort to rush, re-shouldered the ammunition before moving off to their next fire position, on the heel of the forest covering the open ground.

Читать дальше