The President looked thoughtful. “And our conventional response?”

“Despite their numbers we are ready for them. The Baltic Fleet will harass and interdict NATO’s naval and amphibious forces as it sails east to conduct landings on the Estonian coast. Even if the invasion force succeeds in getting through and landing on the beaches, 6th Army has established strong defensive positions on the Estonian coast on all the likely invasion beaches, while maintaining mobile armored reserves in depth ready to counter-attack. In the south, 20th Guards Army is deployed on the southern Lithuanian border. I can also report that 2nd Guards Tank Army has moved from its garrison in central Russia, at Samara, and been transferred to Western Military District. Meanwhile, the forces we withdrew from Kaliningrad and Ukraine will continue to contain the Forest Brother insurgency across the Baltic states.

“As for the air battle, NATO will be unable to win air superiority. Our Vorozneh radar in Kaliningrad is the match of anything they have and it can cover out to hundreds of kilometers. That’s enough to keep all of Eastern and Central Europe under surveillance and capable of tracking more than five hundred aircraft simultaneously. Once detected, NATO aircraft will be easy meat for our S-400 and S-500 air defense missile systems as well as our own interceptors. So we are confident that we will retain the air superiority that will allow us to defeat NATO decisively on the ground.”

“What about Kaliningrad? Is there a danger that NATO could try and attack us there?”

“We think not, Vladimir Vladimirovich,” answered the Foreign Minister, who had remained quiet up to now. “NATO goes on endlessly about being purely a defensive alliance. It is one thing to implement Article Five of the Washington Treaty to defend a member state, but quite another to attack Russian sovereign territory. NATO will never get the agreement of the NAC to do that. Apart from anything else, our friends in Athens and Budapest have confirmed they would veto any such proposal.”

Gareyev intervened. “We know that the Americans and British use their Special Forces as the tip of their spear. We have been watching them carefully and I can tell you there are no Special Forces anywhere near Kaliningrad.”

The President looked satisfied; very much more his old self.

Because if the Alliance does attack , Komarov thought to himself, and Russia does see them off as Gareyev clearly believes they would, then the President’s position, and mine alongside him, would be sealed for the rest of his life.

If NATO did the sensible thing and rattled their sabers, but no more, then the result would be the same: the President would have won. He and the President were only at risk if Russia were defeated and were that to happen, every man around this table would be in the same sinking ship. No, on reflection, although these were dangerous times, the President’s fate was firmly linked with that of Russia and it was the same for these men.

The President had not finished, though. “And, of course, just in case any of you are in any doubt, I will not hesitate to send a missile strike into Warsaw or Berlin the moment NATO attacks.”

“Yevgeney Sergeyevich,” he said, looking at the Foreign Minister, “how confident are you that the Americans wouldn’t take our use of tactical nuclear weapons as a pretext for an intercontinental strike?”

“A difficult one, Vladimir Vladimirovich,” came the reply. “On the one hand the Americans won’t risk Armageddon for the sake of a European city or a purely European military target. But, on the other, any use of tactical nuclear weapons on NATO forces, at sea or on land, will inevitably result in American casualties on a massive scale. That’s because of the preponderance of Americans in the force. If any Americans are nuked, then all bets are off. They’ll certainly respond with tactical battlefield weapons and I certainly wouldn’t rule out the American use of intercontinental ballistic nuclear missiles.”

“So the message is to keep any usage strictly limited to the Europeans,” the President said briskly.

Komarov, however, was not fooled by this effort to be decisive and positive. If they were even discussing firing nuclear weapons then something had gone very wrong with the President’s plan. It wasn’t meant to be like this. A month ago he had sensed the tectonic plates were shifting. Now it was clear that they had shifted. The question was: how far and to whose benefit?

2200 hours, Saturday, July 8, 2017

Forest south of Pravdinsk, Kaliningrad, Russia

EIGHTEEN HOURS LATER, an hour after sunset, Morland and the team moved out of their lying-up position. They’d all had more than enough rest, a few mouthfuls of water and something to eat; in Morland’s case some dry biscuits and a can of cold meat from a ration pack he’d managed to find space for in his daysack. Not much , he thought, but better than nothing .

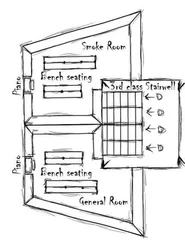

The night was clear and the light drizzle that had fallen as they lay in their hide had cleared. However, the moon had yet to rise and, even when it did—as a waning crescent moon—it would shed little light. They needed luck tonight and the lack of moonlight felt like a good omen. Lukša was once again lead scout and with Sergeant Wild now bringing up the rear as tail-end Charlie, they moved slowly and carefully, following the route they had already recced to the edge of the Drop Zone for American Special Forces. Occasionally they stopped to listen; each time moving into all-round defense and taking up fire positions as a standard drill while they did so. They were listening for danger ahead and off to the sides—sounds they might not hear as they moved through the forest—and also behind, for anyone following them. But all remained quiet.

After a couple of hours, Lukša halted and raised his hand. They were on the edge of the DZ. Again the patrol took cover and moved into all-round defense, this time, though, in a very tight circle, each person’s ankle crossing the ankle of the person to the right of them: now was the time to present as small a target as possible to any roving patrols or wandering civilians.

Morland checked his watch. Twenty-five minutes to go, well ahead of time and roughly as planned. He pointed at his watch to Lukša, who was carrying the radar transponder beacon.

He gave a thumbs up in response to signal his understanding.

The time passed all too slowly. Then it was fifteen minutes to go. Morland again confirmed the time with Sergeant Wild and Lukša, and each compared times on their luminous watches. A thumbs up from each. Now they were on the countdown.

Exactly at a quarter past midnight Lukša activated his handheld radar transponder beacon. It would transmit a response when interrogated by the incoming signal from the descending Special Forces parachutists and would guide the Americans in.

Meanwhile, somewhere thirty kilometers to their south, 30,000 feet above northern Poland, those Americans had jumped from their aircraft about fifty-two minutes earlier. Deploying their parachutes soon after leaving their aircraft, they had crossed into Russian airspace and were now descending by Hi-Glide canopy at around 28 kilometers an hour toward the DZ, guided by the GPS strapped to their wrists and, hopefully, undetected by radar. Right now, as they neared their destination, Morland knew they would be keenly awaiting the return signal from the radar transponder, telling them that there were friendly guides awaiting them at the DZ.

As for Morland, he was suddenly desperate to hear reassuring American voices, backed by American muscle, an indication that he might be taking the first step on his route back to home and some sort of normality.

Читать дальше