‘You still want to help me find Papa?’ asked Shmuel, and Bruno nodded quickly.

‘Of course,’ he said, although finding Shmuel’s papa was not as important in his mind as the prospect of exploring the world on the other side of the fence. ‘I wouldn’t let you down.’

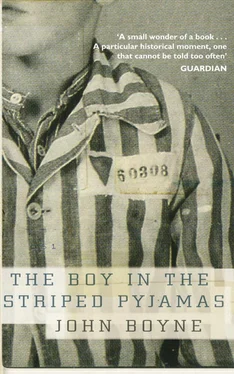

Shmuel lifted the bottom of the fence off the ground and handed the outfit underneath to Bruno, being particularly careful not to let it touch the muddy ground below.

‘Thanks,’ said Bruno, scratching his stubbly head and wondering why he hadn’t remembered to bring a bag to hold his own clothes in. The ground was so dirty here that they would be spoiled if he left them on the ground. He didn’t have a choice really. He could either leave them here until later and accept the fact that they would be entirely caked with mud; or he could call the whole thing off and that, as any explorer of note knows, would have been out of the question.

‘Well, turn round,V said Bruno, pointing at his friend as he stood there awkwardly. ‘I don’t want you watching me.’

Shmuel turned round and Bruno took off his overcoat and placed it as gently as possible on the ground. Then he took off his shirt and shivered for a moment in the cold air before putting on the pyjama top. As it slipped over his head he made the mistake of breathing through his nose; it did not smell very nice.

‘When was this last washed?’ he called out, and Shmuel turned round.

I don’t know if it’s ever been washed,’ said Shmuel.

‘Turn round!’ shouted Bruno, and Shmuel did as he was told. Bruno looked left and right again but there was still no one to be seen, so he began the difficult task of taking off his trousers while keeping one leg and one boot on the ground at the same time. It felt very strange taking off his trousers in the open air and he couldn’t imagine what anyone would think if they saw him doing it, but finally, and with a great deal of effort, he managed to complete the task.

‘There,’ he said. ‘You can turn back now.’

Shmuel turned just as Bruno applied the finishing touch to his costume, placing the striped cloth cap on his head. Shmuel blinked and shook his head. It was quite extraordinary. If it wasn’t for the fact that Bruno was nowhere near as skinny as the boys on his side of the fence, and not quite so pale either, it would have been difficult to tell them apart. It was almost (Shmuel thought) as if they were all exactly the same really.

‘Do you know what this reminds me of?’ asked Bruno, and Shmuel shook his head.

‘What?’ he asked.

‘It reminds me of Grandmother,’ he said. ‘You remember I told you about her? The one who died?’

Shmuel nodded; he remembered because Bruno had talked about her a lot over the course of the year and had told him how fond he had been of Grandmother and how he wished he’d taken the time to write more letters to her before she passed away.

‘It reminds me of the plays she used to put on with Gretel and me,’ Bruno said, looking away from Shmuel as he remembered those days back in Berlin, part of the very few memories now that refused to fade. ‘It reminds me of how she always had the right costume for me to wear. You wear the right outfit and you feel like the person you’re pretending to be, she always told me. I suppose that’s what I’m doing, isn’t it? Pretending to be a person from the other side of the fence.’

‘A Jew, you mean,’ said Shmuel.

‘Yes,’ said Bruno, shifting on his feet a little uncomfortably. ‘That’s right.’

Shmuel pointed at Bruno’s feet and the heavy boots he had taken from the house. ‘You’ll have to leave them behind too,’ he said.

Bruno looked appalled. ‘But the mud,’ he said. ‘You can’t expect me to go barefoot.’

‘You’ll be recognized otherwise,’ said Shmuel. ‘You don’t have any choice.’

Bruno sighed but he knew that his friend was right, and he took off the boots and his socks and left them beside the pile of clothes on the ground. At first it felt horrible putting his bare feet into so much mud; they sank down to his ankles and every time he lifted a foot it felt worse. But then he started to rather enjoy it.

Shmuel reached down and lifted the base of the fence, but it only lifted to a certain height and Bruno had no choice but to roll under it, getting his striped pyjamas completely covered in mud as he did so. He laughed when he looked down at himself. He had never been so filthy in all his life and it felt wonderful.

Shmuel smiled too and the two boys stood awkwardly together for a moment, unaccustomed to being on the same side of the fence.

Bruno had an urge to give Shmuel a hug, just to let him know how much he liked him and how much he’d enjoyed talking to him over the last year.

Shmuel had an urge to give Bruno a hug too, just to thank him for all his many kindnesses, and his gifts of food, and the fact that he was going to help him find Papa.

Neither of them did hug each other though, and instead they began the walk away from the fence and towards the camp, a walk that Shmuel had done almost every day for a year now, when he had escaped the eyes of the soldiers and managed to get to that one part of Out-With that didn’t seem to be guarded all the time, a place where he had been lucky enough to meet a friend like Bruno.

It didn’t take long to get where they were going. Bruno opened his eyes in wonder at the things he saw. In his imagination he had thought that all the huts were full of happy families, some of whom sat outside on rocking chairs in the evening and told stories about how things were so much better when they were children and they’d had respect for their elders, not like the children nowadays. He thought that all the boys and girls who lived here would be in different groups, playing tennis or football, skipping and drawing out squares for hopscotch on the ground.

He had thought that there would be a shop in the centre, and maybe a small cafe like the ones he had known in Berlin; he had wondered whether there would be a fruit and vegetable stall.

As it turned out, all the things that he thought might be there-weren’t.

There were no grown-ups sitting on rocking chairs on their porches.

And the children weren’t playing games in groups.

And not only was there not a fruit and vegetable stall, but there wasn’t a cafe either like there had been back in Berlin.

Instead there were crowds of people sitting together in groups, staring at the ground, looking horribly sad; they all had one thing in common: they were all terribly skinny and their eyes were sunken and they all had shaved heads, which Bruno thought must have meant there had been an outbreak of lice here too.

In one corner Bruno could see three soldiers who seemed to be in charge of a group of about twenty men. They were shouting at them, and some of the men had fallen to their knees and were remaining there with their heads in their hands.

In another corner he could see more soldiers standing around and laughing and looking down the barrels of their guns, aiming them in random directions, but not firing them.

In fact everywhere he looked, all he could see was two different types of people: either happy, laughing, shouting soldiers in their uniforms or unhappy, crying people in their striped pyjamas, most of whom seemed to be staring into space as if they were actually asleep.

‘I don’t think I like it here,’ said Bruno after a while.

‘Neither do I,’ said Shmuel.

‘I think I ought to go home,’ said Bruno.

Shmuel stopped walking and stared at him. ‘But Papa,’ he said. ‘You said you’d help me find him.’

Bruno thought about it. He had promised his friend that and he wasn’t the sort to go back on a promise, especially when it was the last time they were going to see each other. ‘AH right,’ he said, although he felt a lot less confident now than he had before. ‘But where should we look?’

Читать дальше