It’s all because of money. That’s the only reason I’m harried, and the only reason people respect me. If I had nothing, who’d trust a schoolboy like me and ask me to take care of their family?

Won-sam was right. Paying condolences was not urgent. Money was. Pil-sun’s father’s request boiled down to money. He must have hoped that Deok-gi would help out with the funeral expenses. He wasn’t asking Deok-gi to take care of his daughter because Deok-gi was a gentleman and would make a perfect son-in-law. Won-sam’s plain words cut straight to the heart of the matter.

My father’s involvement with Gyeong-ae may have started the same way. If my father hadn’t been wealthy, her father would have asked other comrades for favors. My father and I find ourselves in similar situations because we both happen to come from a rich family, that’s all. My father did things his own way, and I’ll do things my way, according to my own character, ideology, and feelings.

With this revelation, Deok-gi repudiated his mother’s comment that Pil-sun was “a second Gyeong-ae.”

But what is money? Where does it come from? He asked these questions, yet he avoided answering them. He wanted to believe that he was now visiting Pil-sun and her mother to pay his condolences as Deok-gi, not as a benefactor.

He wanted to make sure that Pil-sun would not be spending the night in a chilly, dismal, wood-floored room. As he entered the hospital, it occurred to him that he hadn’t sent enough money. He regretted not sending more, regardless of his feelings for Pil-sun.

Someone who was poor, whose lot in life was hard labor, shouldn’t he at least receive an appropriate compensation for his pains? With this notion taking root in his head, it became clear to Deok-gi that looking after Pil-sun and her mother was his obligation, his duty.

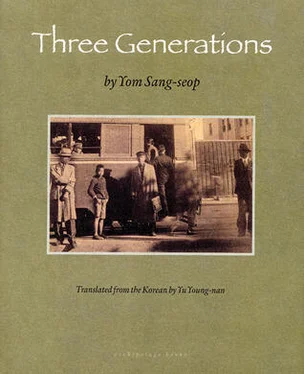

Korea had been in Japan’s colonial clutches for twenty-one years when Yom Sang-seop’s Three Generations appeared in 1931. This milestone in the history of Korean fiction was serialized in the Seoul daily Chosun Ilbo from January through September of that year. During the Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945), newspapers provided practically the only channel in publishing novels because the market was not mature enough to support long works of fiction except for a few eye-catching ones. A majority of writers, Yom included, started their careers as newspaper reporters, creating a climate in which journalists and literary figures commingled amicably. In turn, novels in newspapers tended to boost newspaper sales.

Dreaming of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japan had begun to reinforce its colonial policy and flex its military muscle, with the northward advancement to Manchuria under way. Some Korean writers expressed their opposition to the colonial reality by joining the independence movement whenever opportunities arose or incorporating such material in their works. Others bowed to the Japanese imperialists’ tactics of oppression and appeasement and participated in pro-Japanese activities.

Yom, born in Seoul in 1897, went to Japan to study in 1912. He finished high school there and entered Keio University. After finishing only a semester, however, he joined a regional newspaper as a journalist. He had been studying literature on his own and, in 1919, he joined forces with Hwang Seok-u to create a literary magazine. Soon after, he learned about the March 1 Independence Movement in Korea and became involved in planning a similar rally in Osaka, mobilizing Korean students and workers. He was arrested by the Japanese police and sentenced to ten months in prison at the first trial but was acquitted in the appeals court. He returned to Seoul in 1920 and joined the Dong-A Ilbo daily as a reporter. He participated in the founding of The Ruins, a literary magazine that would soon find a prominent place for itself in the Korean literary landscape. In 1921, his story “Frog in the Specimen Room” appeared in the literary journal Dawn of History, and, a year later, On the Eve of the Uprising (entitled Cemetery at its inception) — one of Yom’s most defining works — came out.

He went to Japan in 1926 and devoted himself to writing fiction. He wrote two novels — Love and Crime and Two Minds — before he returned home in 1928, married Kim Yeong-ok, and joined the Chosun Ilbo daily as the head of its Arts and Science section. While at the paper, his third novel Running Wild appeared.

Three Generations invoked little interest while it came out in serial form, and no criticism on the work was published during the colonial period. It managed to evade the Japanese authorities’ attention. Despite the novel’s importance, it was published in book form only in November 1948, three years after Korea’s liberation from Japan. At the time of publication, the author revised the second half of the book, making the ending more optimistic. Some critics believe that the revision reflects his changed outlook in the wake of the liberation. Compared with the serialized novel, this version focuses more on Deok-gi’s family history than socialist activism.

The novel revolves around a passionate quest for new ideology and the negative climate that thwarts this quest; lurking behind the seemingly long-winded narrative is the author’s critical eye. The characters in this work are not the figures involved in exciting adventures who take readers into the whirlwind of the times; rather, they are ordinary people carrying on their lives during the colonial period. Kim Dong-in, a well-known writer and Yom’s contemporary, described Yom’s works as putting readers under the weight of a “dull pain.”

Three Generations depicts, in a prodding fashion, the mental landscape under the colonial rule from a pessimistic perspective. With the lively use of language of Jungin, or the traditional middle class, to which the author belonged, he manages to reveal the sensibility of this class, which played a pioneering role in the history of Korea’s enlightenment (late 19th century). The story gives shape to the confrontation and conflict of three generations — the late Joseon Dynasty, the enlightenment period, and the colonial era.

The Korean Literary History (1997), penned by Kim Yun-sik and Kim Hyeon, assesses Yom as “revealing the limitations of the society at the time and simultaneously those of his own class.” They go on to say, “Since the Korean society he criticizes is the one perceived by the Jungin class, he takes on the appearance of reactionism.”

In 1924, with the formation of the Korean Artist Proletarian Federation (KAPF), proletarian literature became the mainstay of Korean literature. Yom challenged this faction. In a critical article entitled “Refuting Bak Yeong-hui’s View in Discussing Newly Emerging Literature,” he supported the national literature movement, with its basic thrust of “digging out what is Korean,” which was in opposition to the proletarian literary movement, whose focus was the liberation of the oppressed. While his commitment to this liberation was unwavering, Yom insisted that the quest for Korean-ness should come first. He embraced tradition and the possibility of bringing new, unfettered life to traditional forms; he recognized the sustaining value of sijo, a traditional verse form (or folk song), with a conviction beyond nostalgia. He believed that a literary work was the reflection of the writer’s character and moral influence and that traditional forms of literature could serve as vessels for the vision of the modern writer. In response, Kim Gi-jin, a core figure of the KAPF, disparaged Yom’s argument as a “variation of ultra-nationalism, conservatism, and idealism.”

Читать дальше