Stig Dagerman - Island of the Doomed

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Stig Dagerman - Island of the Doomed» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Univ Of Minnesota Press, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

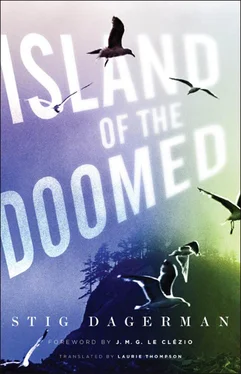

- Название:Island of the Doomed

- Автор:

- Издательство:Univ Of Minnesota Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Island of the Doomed: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Island of the Doomed»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

. This novel was unlike any other yet seen in Sweden and would establish him as the country’s brightest literary star. To this day it is a singular work of fiction — a haunting tale that oscillates around seven castaways as they await their inevitable death on a desert island populated by blind gulls and hordes of iguanas. At the center of the island is a poisonous lagoon, where a strange fish swims in circles and devours anything in its path. As we are taken into the lives of each castaway, it becomes clear that Dagerman’s true subject is the nature of horror itself.

Island of the Doomed

Island of the Doomed — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Island of the Doomed», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

7

There’s a point in a person’s life which exists so as not to be intruded upon. It’s like a little, blue mountain peak which, bluer and sharper than the darkness, shoots up out of the darkness, and an invisible lighthouse which only operates occasionally during your lifetime and then for the shortest of times flings out a serpentine beam of dazzling light into the night, illuminating it for one dizzy second — just one second, but that’s enough. The darkness itself seems to be cloven by a terrible wall of light and you’re drawn implacably towards it like a moth and then suddenly it’s all over: the light goes out, but it’s still burning on your retina and with eyes burning with light, you grope your way forward to a particular spot whose existence you’ve only suspected before, ready for anything, ready to come up against both salvation and destruction, the whole truth or the whole lie. And fumbling through the darkness but with deep wounds of light, you fling your arms around that little mountain peak, that fortress of ruthlessness, where everything hounded, cast aside, silenced clings on like a leech, and you become nothing more than a giant leech sucked hard against the mountain, while everything you believed was prescribed bites on to the nipples of your terror. Nothing is prescribed, nothing can be prescribed: not a thought, not an action, not a word; that’s the terrible thing about living as you do, without fear in a darkness which you think is definitive but which is really just a respite before the lighthouse flares up. Just think how much you wish you’d been blind, so that you could have been spared this final light as well, this light which is so terrible because its ruthless edge cuts through even the most tightly shut of eyelids — and as you end up lying there in the night clamped to your blue stone and being breastfed by all the forgotten horrors, you’d scream if you weren’t the leech you are: why only now, why didn’t I come this way before, why didn’t I take the strokes I needed to swim into range of this invisible lighthouse? I knew all the time where it was and how the little mountain peak lay in wait, crouching like an animal, enticing with its claws and its leeches which only grew more savage the more time passed by. I’ve known about this for a long time, but I relied on flight as being the most crafty deceit of all; but as I was running away I was constantly aware of certain signposts whose enamel had been chipped away by flying stones, of certain snakeskins which had been nailed fast to the road by heavy vehicles, of certain glowworms crushed by some mad fury and piled up by the roadside, and hence knew I was getting closer and closer to the horrors. Then suddenly it was too late: one is transfixed by the violent shaft of light and in the darkness is a blue vortex which knows no mercy.

There’s something in the very air which rouses her and she awakes with a start and looks round quickly and suspiciously — but she’s alone. There are still rustling sounds in the thickets and the grass: someone is slinking or running in towards the middle of the island, but after a while it’s probably just the wind through the tops of the grass. Even so, she stays there for a while yet, her gaze flitting like a grieving dog backwards and forwards along the thin strip of sand, punctuated by steep cliffs. She’s stood here before and gazed down at the beach, but it’s always been different, always been alive, and never has it been so narrow. It looks as if the water has started to rise slowly, slowly but absolutely inevitably, determined to creep up the island and lick off all the dryness, all the desert dryness the water is thirsting for. But then her gaze is stopped short at the burnt-out fire and the dead, singed hollow is just as far from the water’s edge as ever it was and a remarkable, a strange blue deepening of the air, a tall, narrow shadow pointing straight up into the sky above the fireplace still reminds her of the smoke that once was the stuff that hopes were built on, and the acrid smell of unwillingly burning wood still tickles her face when she closes her eyes. She could wake up after dreaming about a burning house with pale faces darting about behind the window panes cracked by the heat, without ever wanting to save them; but she borrowed a pair of binoculars from the chief fire officer and saw they were in fact balloons with faces painted on to them, jerking about on their strings in an effort to break loose, but they always burst with a loud bang and she would wake up from the crackling sounds in the fire. Good God, is it the fire that makes the beach so horribly deserted, so horribly dead?

The graves are also there, the water keg is bobbing securely against the beach, and there are the lines she made in the sand, the sharply outlined furrows in the sand she used to flee to when she wanted to be alone. Then, at that very moment, her gaze wrenches itself away from her will and makes a mad leap out into the water, a leap throbbing with fear and despair. It races through the water, setting spray flying, then launches into a fast crawl across the lagoon and suddenly is about to dive underneath a floating object when the white thing flings itself at the bold swimmer and blinds it, first with pain and then with mad terror, then with overwhelming relief.

It’s not the boy who has been thrown over the reef by the waves and is now drifting closer and closer to the shore, it’s something else, something quite different, and her gaze returns to the white rock in a calm, smooth breast-stroke. The sun gradually turns red with poppies, and she remembers the lion, and is just about to turn and head for the grass and start thinking about such an easy problem and then return as the sun dips sizzling into the sea and all is well, when all of a sudden her gaze leaps up the cliff and something forgotten, something long since forgotten but lying crushed far below hurls itself upon her gaze, and it’s bleeding when she drags it away and runs along the red curve of the rocky path and the high high bushes close over her and she suddenly notices the smell as it slips a disgusting hood over her head, but she doesn’t stop even so, she has no time to stop.

She’s surprised at being so alone; the world is emptied of all voices and suddenly the world is emptied of all sound. Dripping from all her wounds, she falls down in the grass but even then she doesn’t want to stop, she kicks all around her in desperation but feels she’s only sinking deeper and deeper down into the still-hot earth, the hard earth which is no longer alive, having been stunned by the sun and killed by the grass. There she lies, silent and still, listening to the silence; but she daren’t, can’t listen for long for fear her eardrums will be burst by this highly charged silence.

And the smell is still after her, creeping like a caterpillar down the long grass stems, and at first, almost without any fear at all, she tastes it and tries to recall this smell. It’s the sort of smell you might find in a cellar, it’s a smell which requires you to go down many flights of stairs with a bunch of keys rattling from your finger, then you open a door, many doors, the last of them heavy monsters of doors you have to heave against with your shoulder before they slide open, creaking and squealing. This is a smell for the dark, for cellars, or for some other dark places. It needs a lamp, an insignificant flashlamp projecting its frightened glances into every corner of the darkness and only succeeding in making the darkness even more frightening and the smell even more mysterious. It’s a smell for felt soles, the sort you take long strides with when you’re running around in wet grass so that the damp won’t go through them and because you’re frightened of snakes. It’s a smell that has to be overcome by stealth, a smell you must hurl yourself at and fight with for a while, bite, and fling your arms round to crush it. It’s a smell that requires you to go right into the cellar and put the flashight down on the floor so that it just surrounds itself with a little hazy circle of light which doesn’t even reach as far up as the dripping stone ceiling. Then there are things to be shifted out of the way: firewood, heavy crates with the lids nailed down, keeping mum about what’s in them, odds and ends of fishing tackle with wet seaweed still clinging to them, lots of cracked croquet balls, sacks, empty but tightly knotted sacks of coarse material that rattles — sand, maybe? — when you move them, the odd axe gone rusty because it’s been left out in the rain and nobody’s bothered about it, and perhaps the misshapen skeleton of an old iron cot which still seems to tremble when you lift it up in the air, tremble because it belonged to a child that recently died of tuberculosis, You pile all these things up behind you to make a barrier and it’s so high you can hardly imagine there’s a light behind it and as you stand there enclosed by four walls of darkness and a ceiling of darkness and a floor of darkness you suddenly realize there’s a smell of fear as well, a smell that makes you search all over the cellar for a pickaxe, shaking all the time, and when you find one you start bashing away at the floor behind the barricade, carefully at first so that only cracks appear in the concrete, but then more and more violently, increasingly afraid of all kinds of things: of the people in the house waking up and failing to understand what it’s all about, of finding that looking for the smell under the cellar floor is a waste of time, or that the outcome is as awful as you’re already imagining it will be.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Island of the Doomed»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Island of the Doomed» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Island of the Doomed» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.