He can still remember very clearly that parachute that needed testing, it required fifty-eight stages from when you put it on to when you actually jumped, and he knew them all so perfectly, more perfectly than anyone else, and he counted the seconds mechanically as he approached the door where they were leaping out one after another with their arms spread out and then there was that time when he was on a commuter tram, maybe it was hot or maybe the sliding door was open for some reason or other, anyway, there he was pressed tightly against the wall and in front of him stood a man with a rucksack looking very much like a parachute, and the man moved quickly to one side and disappeared from view and suddenly Boy was in an aeroplane, he started counting to himself and closed his eyes as usual as he staggered the few paces to the door and he grabbed the frame to give himself a thrust outwards and he’d already let go and was just about to jump when somebody grasped him hard by the shoulder and dragged him violently back in again. It was a most embarrassing situation, nobody would believe him if he said he thought he was in an aeroplane, because how could you possibly confuse an aeroplane with a tram, everybody asks. This man just tried to commit suicide, says the tubby little man who’d saved him, inflating himself with his own splendid performance, but I managed to grab him at the last moment, and all the passengers stand up and stare at him in disapproval, and their lips curl in silent contempt as if to say: You go off and commit suicide if you want to, young fellow, but not while we’re here, we don’t want any blood and we don’t want to give evidence or any of the other unpleasantnesses that go with such an occurrence — and poor Boy had to get off at the next stop.

That’s the way it is with disobedience, it can so easily turn the tables on you, it’s so practical for everybody else but very rarely for you, it forces you to do the most outrageous things, and then you get into a fix and you can’t blame somebody else because nobody will believe you anyway. How on earth could you get such a daft idea into your head, they ask with a sneer. I was only obeying orders, you reply without sneering, just obeying orders. But that’s impossible, they say, there aren’t any orders like that, and if there aren’t any such orders, who were you obeying, God or the devil or some other devil? After that really witty punch line they start guffawing and take no notice of any assurances you give which are a waste of time in any case. They don’t see the wound that’s starting to spread all over you, the wound that starts just under your collar, leaves your head and your bare hands free but apart from that spreads all over your body.

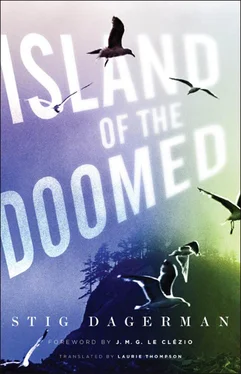

Boy Larus wandered around in the dusk on the stony plateau the size of a skating rink to which he had to flee with his groin wounds in order to avoid the temptation of looking at them, enjoying them, tasting the agonizing pain they provided. Meanwhile, the great flash of twilight that was hurled through the world singed away the little island where six human beings were being tortured together, by their hunger, their thirst, their sorrow, their paralysis. Nights came and went, days came and went, but hunger, thirst, sorrow and paralysis came back refreshed every morning; he saw hopes born, bitter furrows growing deeper, beards growing longer and more brutal, bodies becoming dirtier and smellier, hair growing shaggier and wilder, faces slowly but steadily shrinking as hardships increased, clothes hanging looser and being shredded bit by bit by the island’s sharp edges, backs growing more rounded and submissive, eyes more defiant and crazed from lack of sleep and lack of hope, skins rougher, more sunburnt and covered more and more in nasty spots, feet growing more blood-stained and more careless about where they trod, words becoming fewer and more blood-stained and more careless about where they trod, arms thinner and ever more helpless, elbows more pointed and pitiful, skin stretching over hip-bones, kneecaps, ribs, collar-bones, elbows, finger-joints, knuckles, nasal bones, temples, frontal bones, jaws, cheek-bones, vertebrae, shin-bones, thigh-bones, wrists, pelvises and crania — but even so he felt he was in another world, like a man lost in a menagerie: maybe he won’t find his way out before dusk falls, but sooner or later the caretaker will turn up; he raced around between the locked cages, hoping they were locked at least, and searched in vain for the exit while the lion roared and heavy snakes rattled behind their glass screens, monkeys howled frenziedly, relentlessly, shrilly, and a solitary tiger raged somewhere in the darkness. Indeed, he was always backing off from the wild animals staring at him from his companions’ eyes, from their faces and bodies. There seemed to be no barriers holding them back, no wounds too shameful to display, their ruthlessness terrified him so much he felt like screaming, so that he too could feel this wild urge to tear off his clothes and bellow: look, I’ve also got wounds that hurt, spreading all over me, sinking into me, driving me mad with agony. Look at them with your greedy eyes, feel them with your greedy hands, kiss them with your greedy lips.

Oh, how scared he was of them, and how comforting it was to feel the green flash and its surging heat sweep them out of this world, from this wonderful world of shattered hopes, disciplined coolness, and vacuous freedom from problems. He walked over to the mound, which looked as if it might have been made by human hand as a bulwark, so regular was its height over the rock, so carefully was it thought out as a protection for someone afraid of a rear attack, a surprise attack and any other kind of treachery. It ran round a third of his plateau and had red streaks like no other stones on the whole island. On top of it were mysterious black hollows looking like some strange form of box; he tried to work out what could have been pressed into the rock only to be squashed just as everything stiffened up. He took a little stone and knocked inside the boxes, but nowhere was the stone as hard as it was here, and all he could do was produce a few shallow little scratches. Then he ran his fingers slowly over the contours, closed his eyes and tried to shut out everything except his fingers, to force his senses through the hard outer shell and find out what there was living inside there, to try and hear the music that must be trapped inside, still being sung even after millions of years in captivity.

But he himself was dead, his fingers were so insensitive, their skin felt like sandpaper, and his ear could hear nothing, apart from the soughing of the wind as it drifted along the autostrada of the dusk.

Oh, those fingers of his, they used to be so long and sensitive. You’ll see, my dear, you’ll be a musician when you grow up, said all too many people; to be sure, he had become quite an artist on the machine gun and had the longest fingers in the whole company. There was a certain tune in the aeroplane, no, not in the aeroplane but in the air round about it, which reminded him of a melody he’d once heard at a funeral, and it came just when they had to bank and gain height at the same time. Now his ears weren’t much good either. He kneeled down and stroked the stone, listening for the captive voice even though he knew how pointless it was.

Then he came to with a start, for something was moving fast just below him, something was on its way up to him, something indescribably horrible, something that wanted to leap on top of him and bite off all these membranes anchoring him to life. He looked up, but it was only the smoke from the fire down below which had changed direction, the green dusk had acquired long, black shadows sailing through it, darkness was seeping in from all sides and the dazzling white smoke wavered gently and floated slowly up towards him in wisps. He looked down at the camp, the grass and the tall bushes were in the way; the ship was slumped as usual over the reef, however, and the strange green light was still dallying in the undamaged portholes, the funnel was leaning over the bridge and seemed to be involved in intimate conversation with the mast, which was leaning backwards, broad-chested and as yet unbowed, a solid countryman sniffing the morning weather with hands in pockets, and the cook’s hat had got caught on a wire and was fluttering backwards and forwards as if looking for a head to settle on. The water was still shimmering slightly but obviously sensitive to the falling darkness, and he thought he could see something floating towards him; he was suddenly scared and tried to close his eyes, but they refused to obey. Something drifted slowly forwards about a hundred yards to stern: was that white patch a human being, or a part of a human being slowly surfacing on an undercurrent?

Читать дальше