Oh yes, she knew all of them. The makes of their cars varied, as did the colour of their jackets and the way they sipped their cognac, but they all shared that cowardice dressed up as strength, they always started their seduction in the same, brutal way which was so funny because it seemed to leave so little room for variations, it was like reading the same syndicalized leader in the same newspaper day out and day in, and the result was always just as uninteresting and clumsily offensive. They thought they were skilful and knew all there was to know about women, and you could put up with observing ironically their ridiculous self-confidence as long as it remained within the bounds of moderation and harmless self-deception; but when they started being insolent and, because of their imagined skills, insisted shamelessly on complete surrender to all their peculiar whims, then she had to call a halt.

And my God, it was so easy; the slightest little obstacle in the way of the programme they’d planned which boded no awkward surprises, and they immediately became irritable and their strength drained away as if a plug had been pulled out of their pounding chests. After all, their programme was intended to run for all eternity, and there was no room for anybody tampering with it: after a few phrases about the weather, the moonlight, the latest news from the racing circuits, the splendid qualities of the car, her own mouth and her own hair, fate had decreed that the next step was to kiss, and so the car came to a halt half a mile short of the little side road. Five minutes later it was time to turn down it and stop at the little sloping glade fate always seems to have planted alongside minor roads suitably far from inhabited areas. In the same old deathly silence, one would return to the car, cold and wet from the grass, and the journey home would soon pass, the only replies one received were inaudible mutterings, and one would be dropped off with the necessary degree of rudeness outside one’s front door, if one was lucky and the garage wasn’t situated in some other part of town.

Faces flicker past like stills from a film as she gazes into the darkness of her cupped hands. Percival, the one with the yellow car, the insufferable bore who always whistled as they got to their feet afterwards; Charles, who died later in some accident involving gas and was one of the most inoffensive; Lucien, one of the few who drove just as fast on the way out as he did on the way back; Henri, who could not help crying like a spoilt child when he was not allowed to be as brutal as he needed to be if he were to make it; Jean, the gentleman who had already achieved middle age and was so afraid of his reputation that he forbade her to walk past the house he lived in, not far from hers; Jacques, young Jacques, who was so young he thought he knew all there was to know, and was about to be enlightened where women were concerned. That’s why she was so keen to conquer him. All right, he was so sweet when a quiff of hair fell down over his forehead and he was too preoccupied with something to notice; his eyes were never still for a second, not even when he was kissing her, but he was so sure of her, despite the difference in their age, or because of it perhaps, that he demanded she should submit herself without reservation to his tyrannical programme.

They’d come to a little headland, quite high up and in the middle of the night; water had been flowing down below on both sides, the air was warm and yet fresh at the same time, the peace was so immense that she hardly dared breathe as they got out of the car. Then he got it into his head that the engine should be running all the time, and she protested, gently at first but increasingly energetically. It offended his vanity that she refused to submit immediately, and so he revved up the engine until it was roaring like a bull into the night. Then he grabbed her roughly by the arm and pushed her in front of him to the tip of the headland, but when he tried to force her down, she just started laughing. She realized of course it was the car he really wanted to make love to, not her: her gasps and whispered words of passion would be drowned by the roaring of the car.

‘What are you laughing at?’ he asked; she could feel the tight grip he had on her arm slackening off, and noticed with satisfaction the acrimonious insecurity in his voice.

Of course, she didn’t answer, just carried on laughing as before, demolishing his great self-confidence bit by bit, and when she was finally convinced he was conquered once and for all, she pulled him to her urgently and they sank down together. Everything had gone as she knew it would; he plucked nervously at her clothes, and afterwards he jerked himself violently away from her and lay in the grass, abandoned to his own sobs.

She went back and sat in the car, and when he’d finished crying he returned and started the car with a tremendous jolt, then hurtled off through the darkness and silence at a hysterical speed, brushing against tree trunks and buckling the right wing and losing a headlight; but Jacques kept on driving like a madman until they came to the turning from the side road on to the main road when he lost control for a split second and they crashed into a milk lorry which skidded into a ditch. The smash ripped the door off one of its hinges, but that only made him drive even faster. Strangely enough she was quite calm, and it was not until some days later she grew scared when she thought of what might have happened. She realized of course he was only seeking revenge for his defeat, but that he would never be able to achieve it. She was just enjoying herself instead of being scared, enjoying the wind whistling past their ears and the black road which seemed to be spinning away beneath them. She remembered that night for the rest of her life, and the more frigid she became, the brighter the halo grew over her night with Jacques; she adorned the memory with flowers and garlands, built a triumphal arch around it, and the more frigid she became, the higher the arch grew.

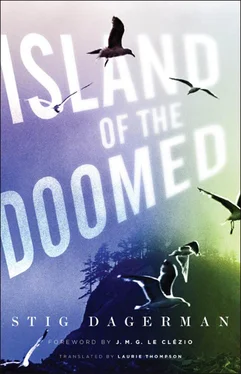

But when she remembered it now on the island, it was not for the sake of her triumph — sorrow comes with great humility — but because it marked the end of something and the beginning of something else, the beginning of something which would finally force her into a solitude which was greater than most other people’s, the beginning of something which eventually, one day at sunset, made her crush an innocent iguana with a heavy, round stone.

No more cars screeched to a halt outside her front door, no horns sounded to bring her running to the window. Apart from a few walks in the immediate vicinity together with her housekeeper Mile Claire, she would spend all her time in an armchair in her room, sorting out Paul’s stamp collection or pasting her amateurish photographs into blue albums, something she’d put off for far too long.

She’d been standing in Paul’s room with her back towards him the day after the interlude with Jacques. She had tensed her back as hard as she could in order to withstand everything that was now engulfing her, but in the end, she was unable to resist any more. It was as if her back caved in, she fell to her knees and ground her head red against the windowsill, pressed her burning face against the wall in order to avoid the temptation of looking at the cripple in the bed.

‘You must think I’m deaf and dumb, but that’s not true as you may be aware, what I am is crippled. You think I can’t hear your laughter echoing throughout the flat, you think I can’t hear the sweet nothings at the front door, and the young boys in their cars queueing up outside.’

‘Don’t be silly, I’ve never made any secret of the fact that I sometimes go out for a bit of fun. I can’t wander about in this big house on my own all the time.’

Читать дальше