Mark Twain - Following the Equator

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Twain - Following the Equator» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Жанр: Классическая проза, Юмористическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Following the Equator

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Following the Equator: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Following the Equator»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Following the Equator — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Following the Equator», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

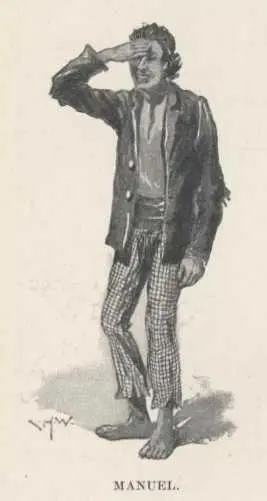

We had to have some one right away; so the family went down stairs and took him a week on trial; then sent him up to me and departed on their affairs. I was shut up in my quarters with a bronchial cough, and glad to have something fresh to look at, something new to play with. Manuel filled the bill; Manuel was very welcome. He was toward fifty years old, tall, slender, with a slight stoop—an artificial stoop, a deferential stoop, a stoop rigidified by long habit—with face of European mould; short hair intensely black; gentle black eyes, timid black eyes, indeed; complexion very dark, nearly black in fact; face smooth-shaven. He was bareheaded and barefooted, and was never otherwise while his week with us lasted; his clothing was European, cheap, flimsy, and showed much wear.

He stood before me and inclined his head (and body) in the pathetic Indian way, touching his forehead with the finger-ends of his right hand, in salute. I said:

"Manuel, you are evidently Indian, but you seem to have a Spanish name when you put it all together. How is that?"

A perplexed look gathered in his face; it was plain that he had not understood—but he didn't let on. He spoke back placidly.

"Name, Manuel. Yes, master."

"I know; but how did you get the name?"

"Oh, yes, I suppose. Think happen so. Father same name, not mother."

I saw that I must simplify my language and spread my words apart, if I would be understood by this English scholar.

"Well—then—how—did—your—father—get—his name?"

"Oh, he,"—brightening a little—"he Christian—Portygee; live in Goa; I born Goa; mother not Portygee, mother native-high-caste Brahmin—Coolin Brahmin; highest caste; no other so high caste. I high-caste Brahmin, too. Christian, too, same like father; high-caste Christian Brahmin, master—Salvation Army."

All this haltingly, and with difficulty. Then he had an inspiration, and began to pour out a flood of words that I could make nothing of; so I said:

"There—don't do that. I can't understand Hindostani."

"Not Hindostani, master—English. Always I speaking English sometimes when I talking every day all the time at you."

"Very well, stick to that; that is intelligible. It is not up to my hopes, it is not up to the promise of the recommendations, still it is English, and I understand it. Don't elaborate it; I don't like elaborations when they are crippled by uncertainty of touch."

"Master?"

"Oh, never mind; it was only a random thought; I didn't expect you to understand it. How did you get your English; is it an acquirement, or just a gift of God?"

After some hesitation—piously:

"Yes, he very good. Christian god very good, Hindoo god very good, too. Two million Hindoo god, one Christian god—make two million and one. All mine; two million and one god. I got a plenty. Sometime I pray all time at those, keep it up, go all time every day; give something at shrine, all good for me, make me better man; good for me, good for my family, dam good."

Then he had another inspiration, and went rambling off into fervent confusions and incoherencies, and I had to stop him again. I thought we had talked enough, so I told him to go to the bathroom and clean it up and remove the slops—this to get rid of him. He went away, seeming to understand, and got out some of my clothes and began to brush them. I repeated my desire several times, simplifying and re-simplifying it, and at last he got the idea. Then he went away and put a coolie at the work, and explained that he would lose caste if he did it himself; it would be pollution, by the law of his caste, and it would cost him a deal of fuss and trouble to purify himself and accomplish his rehabilitation. He said that that kind of work was strictly forbidden to persons of caste, and as strictly restricted to the very bottom layer of Hindoo society—the despised 'Sudra' (the toiler, the laborer). He was right; and apparently the poor Sudra has been content with his strange lot, his insulting distinction, for ages and ages—clear back to the beginning of things, so to speak. Buckle says that his name—laborer—is a term of contempt; that it is ordained by the Institutes of Menu (900 B.C.) that if a Sudra sit on a level with his superior he shall be exiled or branded—[Without going into particulars I will remark that as a rule they wear no clothing that would conceal the brand.—M. T.] . . . if he speak contemptuously of his superior or insult him he shall suffer death; if he listen to the reading of the sacred books he shall have burning oil poured in his ears; if he memorize passages from them he shall be killed; if he marry his daughter to a Brahmin the husband shall go to hell for defiling himself by contact with a woman so infinitely his inferior; and that it is forbidden to a Sudra to acquire wealth. "The bulk of the population of India," says Bucklet—[Population to-day, 300,000,000.]—"is the Sudras—the workers, the farmers, the creators of wealth."

Manuel was a failure, poor old fellow. His age was against him. He was desperately slow and phenomenally forgetful. When he went three blocks on an errand he would be gone two hours, and then forget what it was he went for. When he packed a trunk it took him forever, and the trunk's contents were an unimaginable chaos when he got done. He couldn't wait satisfactorily at table—a prime defect, for if you haven't your own servant in an Indian hotel you are likely to have a slow time of it and go away hungry. We couldn't understand his English; he couldn't understand ours; and when we found that he couldn't understand his own, it seemed time for us to part. I had to discharge him; there was no help for it. But I did it as kindly as I could, and as gently. We must part, said I, but I hoped we should meet again in a better world. It was not true, but it was only a little thing to say, and saved his feelings and cost me nothing.

But now that he was gone, and was off my mind and heart, my spirits began to rise at once, and I was soon feeling brisk and ready to go out and have adventures. Then his newly-hired successor flitted in, touched his forehead, and began to fly around here, there, and everywhere, on his velvet feet, and in five minutes he had everything in the room "ship-shape and Bristol fashion," as the sailors say, and was standing at the salute, waiting for orders. Dear me, what a rustler he was after the slumbrous way of Manuel, poor old slug! All my heart, all my affection, all my admiration, went out spontaneously to this frisky little forked black thing, this compact and compressed incarnation of energy and force and promptness and celerity and confidence, this smart, smily, engaging, shiney-eyed little devil, feruled on his upper end by a gleaming fire-coal of a fez with a red-hot tassel dangling from it. I said, with deep satisfaction—

"You'll suit. What is your name?"

He reeled it mellowly off.

"Let me see if I can make a selection out of it—for business uses, I mean; we will keep the rest for Sundays. Give it to me in installments."

He did it. But there did not seem to be any short ones, except Mousa—which suggested mouse. It was out of character; it was too soft, too quiet, too conservative; it didn't fit his splendid style. I considered, and said—

"Mousa is short enough, but I don't quite like it. It seems colorless—inharmonious—inadequate; and I am sensitive to such things. How do you think Satan would do?"

"Yes, master. Satan do wair good."

It was his way of saying "very good."

There was a rap at the door. Satan covered the ground with a single skip; there was a word or two of Hindostani, then he disappeared. Three minutes later he was before me again, militarily erect, and waiting for me to speak first.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Following the Equator»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Following the Equator» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Following the Equator» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.