Mark Twain - Following the Equator

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Twain - Following the Equator» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Жанр: Классическая проза, Юмористическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Following the Equator

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Following the Equator: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Following the Equator»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Following the Equator — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Following the Equator», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I saw the same man leap from the ground, and in going over he dipped his head, unaided by his hands, into a hat placed in an inverted position on the top of the head of another man sitting upright on horseback—both man and horse being of the average size. The native landed on the other side of the horse with the hat fairly on his head. The prodigious height of the leap, and the precision with which it was taken so as to enable him to dip his head into the hat, exceeded any feat of the kind I have ever beheld."

I should think so! On board a ship lately I saw a young Oxford athlete run four steps and spring into the air and squirm his hips by a side-twist over a bar that was five and one-half feet high; but he could not have stood still and cleared a bar that was four feet high. I know this, because I tried it myself.

One can see now where the kangaroo learned its art.

Sir George Grey and Mr. Eyre testify that the natives dug wells fourteen or fifteen feet deep and two feet in diameter at the bore—dug them in the sand—wells that were "quite circular, carried straight down, and the work beautifully executed."

Their tools were their hands and feet. How did they throw sand out from such a depth? How could they stoop down and get it, with only two feet of space to stoop in? How did they keep that sand-pipe from caving in on them? I do not know. Still, they did manage those seeming impossibilities. Swallowed the sand, may be.

Mr. Chauncy speaks highly of the patience and skill and alert intelligence of the native huntsman when he is stalking the emu, the kangaroo, and other game:

"As he walks through the bush his step is light, elastic, and noiseless; every track on the earth catches his keen eye; a leaf, or fragment of a stick turned, or a blade of grass recently bent by the tread of one of the lower animals, instantly arrests his attention; in fact, nothing escapes his quick and powerful sight on the ground, in the trees, or in the distance, which may supply him with a meal or warn him of danger. A little examination of the trunk of a tree which may be nearly covered with the scratches of opossums ascending and descending is sufficient to inform him whether one went up the night before without coming down again or not."

Fennimore Cooper lost his chance. He would have known how to value these people. He wouldn't have traded the dullest of them for the brightest Mohawk he ever invented.

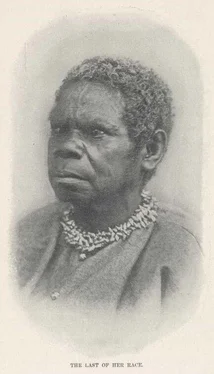

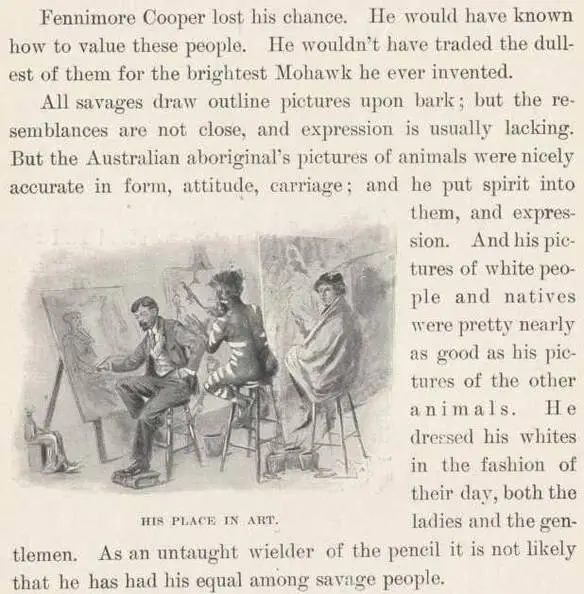

All savages draw outline pictures upon bark; but the resemblances are not close, and expression is usually lacking. But the Australian aboriginal's pictures of animals were nicely accurate in form, attitude, carriage; and he put spirit into them, and expression. And his pictures of white people and natives were pretty nearly as good as his pictures of the other animals. He dressed his whites in the fashion of their day, both the ladies and the gentlemen. As an untaught wielder of the pencil it is not likely that he has his equal among savage people.

His place in art—as to drawing, not color-work—is well up, all things considered. His art is not to be classified with savage art at all, but on a plane two degrees above it and one degree above the lowest plane of civilized art. To be exact, his place in art is between Botticelli and De Maurier. That is to say, he could not draw as well as De Maurier but better than Boticelli. In feeling, he resembles both; also in grouping and in his preferences in the matter of subjects. His "corrobboree" of the Australian wilds reappears in De Maurier's Belgravian ballrooms, with clothes and the smirk of civilization added; Botticelli's "Spring" is the "corrobboree" further idealized, but with fewer clothes and more smirk. And well enough as to intention, but—my word!

The aboriginal can make a fire by friction. I have tried that.

All savages are able to stand a good deal of physical pain. The Australian aboriginal has this quality in a well-developed degree. Do not read the following instances if horrors are not pleasant to you. They were recorded by the Rev. Henry N. Wolloston, of Melbourne, who had been a surgeon before he became a clergyman:

1. "In the summer of 1852 I started on horseback from Albany, King George's Sound, to visit at Cape Riche, accompanied by a native on foot. We traveled about forty miles the first day, then camped by a water-hole for the night. After cooking and eating our supper, I observed the native, who had said nothing to me on the subject, collect the hot embers of the fire together, and deliberately place his right foot in the glowing mass for a moment, then suddenly withdraw it, stamping on the ground and uttering a long-drawn guttural sound of mingled pain and satisfaction. This operation he repeated several times. On my inquiring the meaning of his strange conduct, he only said, 'Me carpenter-make 'em' ('I am mending my foot'), and then showed me his charred great toe, the nail of which had been torn off by a tea-tree stump, in which it had been caught during the journey, and the pain of which he had borne with stoical composure until the evening, when he had an opportunity of cauterizing the wound in the primitive manner above described."

And he proceeded on the journey the next day, "as if nothing had happened"—and walked thirty miles. It was a strange idea, to keep a surgeon and then do his own surgery.

2. "A native about twenty-five years of age once applied to me, as a doctor, to extract the wooden barb of a spear, which, during a fight in the bush some four months previously, had entered his chest, just missing the heart, and penetrated the viscera to a considerable depth. The spear had been cut off, leaving the barb behind, which continued to force its way by muscular action gradually toward the back; and when I examined him I could feel a hard substance between the ribs below the left blade-bone. I made a deep incision, and with a pair of forceps extracted the barb, which was made, as usual, of hard wood about four inches long and from half an inch to an inch thick. It was very smooth, and partly digested, so to speak, by the maceration to which it had been exposed during its four months' journey through the body. The wound made by the spear had long since healed, leaving only a small cicatrix; and after the operation, which the native bore without flinching, he appeared to suffer no pain. Indeed, judging from his good state of health, the presence of the foreign matter did not materially annoy him. He was perfectly well in a few days."

But No. 3 is my favorite. Whenever I read it I seem to enjoy all that the patient enjoyed—whatever it was:

3. "Once at King George's Sound a native presented himself to me with one leg only, and requested me to supply him with a wooden leg. He had traveled in this maimed state about ninety-six miles, for this purpose. I examined the limb, which had been severed just below the knee, and found that it had been charred by fire, while about two inches of the partially calcined bone protruded through the flesh. I at once removed this with the saw; and having made as presentable a stump of it as I could, covered the amputated end of the bone with a surrounding of muscle, and kept the patient a few days under my care to allow the wound to heal. On inquiring, the native told me that in a fight with other black-fellows a spear had struck his leg and penetrated the bone below the knee. Finding it was serious, he had recourse to the following crude and barbarous operation, which it appears is not uncommon among these people in their native state. He made a fire, and dug a hole in the earth only sufficiently large to admit his leg, and deep enough to allow the wounded part to be on a level with the surface of the ground. He then surrounded the limb with the live coals or charcoal, which was replenished until the leg was literally burnt off. The cauterization thus applied completely checked the hemorrhage, and he was able in a day or two to hobble down to the Sound, with the aid of a long stout stick, although he was more than a week on the road."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Following the Equator»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Following the Equator» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Following the Equator» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.