John Steinbeck - Once there was a war

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Steinbeck - Once there was a war» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1960, Издательство: Bantam Books, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Once there was a war

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bantam Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1960

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Once there was a war: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Once there was a war»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Once there was a war — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Once there was a war», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

7. Some kind of epidemic has broken out on the ship. The officers are keeping it quiet to prevent a panic. They are burying the dead secretly at night.

As the days go by and the men grow more restless and the parcheesi games have fallen off because the sinews of the game have got into a few lean and hungry hands, the rumors grow more intense. Somewhere in mid-ocean a big patrol plane flies near to us and circles protectively, and the rumor springs up that she has signaled the captain to change course. Something terrific is going on somewhere and we are changing our destination.

Since we change our course every thirty seconds anyway, there is no telling by watching the wake where we are going. So the rumors go. It would be interesting if the ship’s officers would post a list of rumors the men are likely to hear. It would certainly eliminate some apprehensions on the part of the men, and it would be interesting to see whether then a whole new list of fresh, unused rumors would grow up.

SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND, June 24, 1943 —

A small USO unit is aboard this troopship, girls and men who are going out to entertain troops wherever they may be sent. These are not the big names who go out with blasts of publicity and maintain their radio contracts. These are girls who can sing and dance and look pretty and men who can do magic and pantomimists and tellers of jokes. They have few properties and none of the tricks of light and color which dress up the theater. But there is something very gallant about them. The theater is the only institution in the world which has been dying for four thousand years and has never succumbed. It requires tough and devoted people to keep it alive. An accordion is the largest piece of property the troupe carries. The evening dresses, crushed in suitcases, must be pressed and kept pretty. The spirit must be high. This is trouping the really hard way.

The theater is one of the largest mess halls. Soldiers are packed in, sitting on benches, standing on tables, lying in the doorways. A little platform on one end is the stage. Tonight the loudspeaker is out of order, but when it isn’t it blares and distorts voices. The master of ceremonies gets up and faces his packed audience. He tells a joke — but this audience is made up of men from different parts of the country and each part has its own kind of humor. He tells a New York joke. There is a laugh, but a limited one. The men from South Dakota and Oklahoma do not understand this joke. They laugh late, merely because they want to laugh. He tries another joke and this time he plays safe. It is an Army joke about MPs. This time it works. Everybody likes a joke about MPs.

He introduces an acrobatic dancer, a pretty girl with long legs and the strained smile acrobats develop to conceal the fact that their muscles are crying with tension. The ship is rolling slowly from side to side. All of her work is dependent on perfect balance. She tries each part of her act several times and is thrown off balance, but, seriously, she tries again until, in a pause in the ship’s roll she succeeds, and legs are distorted properly for the proper two seconds. The soldiers are with her. They know the difficulty. They want her to succeed and they cheer when she does. This is all very serious. She leaves the stage under whistles and cheers.

A blues singer follows. Without the loudspeakers she can hardly be heard, for her voice, although sweet, has no volume. She forces her voice for volume and loses her sweetness, but she is pretty and young and earnest.

A girl accordion-player comes next. She asks for suggestions. This is to be group singing and the requests are for old songs — “Harvest Moon,” “Home on the Range,” “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling.” The men bellow the words in all pitches. There is no war song for this war. Nothing has come along yet. The show continues — a pantomimist who acts out the physical examination of an inductee and does it so accurately that his audience howls. A magician in traditional tail coat manipulates colored silks.

In all the acts the illusion does not quite come off. The audience helps all it can because it wants the show to be good. And out of the little acts, which are not quite convincing, and the big audience which wants literally to be convinced, something whole and good comes, so that when it is over there has been a show.

One of the men in the unit has been afraid. He has not slept since the ship sailed. He is afraid of the ocean and of submarines. He has lain in his bunk, listening for the blast that will kill him. He is probably very brave. He does his act when he is terrified. It is foolish to say he should not be afraid. He is afraid, and that is something he cannot control, but he does his act, and that is something he can control.

Up on the deck in the blackness the colored troops are sprawled. They sit quietly. A great bass voice sings softly a bar of the hymn “When the Saints Go Marching In.” A voice says, “Sing it, brother!”

The bass takes it again and a few other voices join him. By the time the hymn has reached the fourth bar an organ of voices is behind it. The voices take on a beat, feeling one another out. The chords begin to form. There is nothing visible. The booming voices come out of the darkness. The men sing sprawled out, lying on their backs. The song becomes huge with authority. This is a war song. This could be the war song. Not the sentimental wash about lights coming on again or bluebirds.

The black deck rolls with sound. One chorus ends and another starts, “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Four times and on the fifth the voices fade away to a little hum and the deck is silent again. The ship rolls and metal protests against metal. The ship is silent again. Only the shudder of the engine and the whisk of water and the whine of the wind in the wire rigging break the silence.

We have not yet a singing Army nor any songs for a singing Army. Synthetic emotions and nostalgias do not take hold because the troops know instinctively that they are synthetic. No one has yet put words and a melody to the real homesickness, the real terror, and the real ferocity of the war.

SOMEWHERE IN ENGLAND, June 25, 1943 —

We are coming close to land. The birds picked us up this morning and a big flying boat circled us and then darted away to report us. There has been no trouble at all, and if, on the bridge, the enemy has been reported, we do not know it. The word sifts down from the bridge that we shall land tonight. The soldiers line the rails and report every low-hanging cloud as a landfall. Now that we are near and the lines of our approach are narrow, the danger is greater. The ship swerves and turns constantly. These waters are the most dangerous of all.

The men are reading a little booklet that has been distributed, telling them how to get along with the English. The book explains language differences. It suggests that in England a closet is not a place to hang clothing, that the word “bloody” should be avoided, that a garbage can is a dust bin, and it warns that the English use many common words with a meaning different from what we assign to them. Many of our men find this very funny and they go about talking a curious gibberish which they imagine is a British accent.

A light haze shrouds the horizon, and out of it our Spitfires drive at us and circle like angry bees. They come so close that we hear the fierce whistle of their wings. For a long time they circle us and then go away, and others take their place.

In the afternoon land shows through the haze and, as we get closer, the neat houses and the neat country, orderly and old. The men gaze at it in wonder. It is the first foreign place most of them have ever seen and each man says it looks like some place he knows. One says it looks like California in the springtime of a wet year. Another recognizes Vermont. The men crowd to the portholes and the rails.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

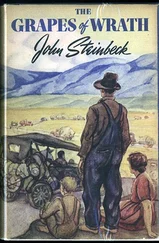

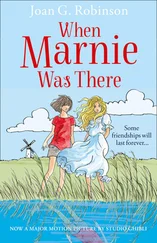

Похожие книги на «Once there was a war»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Once there was a war» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Once there was a war» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.