John Steinbeck - Once there was a war

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Steinbeck - Once there was a war» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1960, Издательство: Bantam Books, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Once there was a war

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bantam Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1960

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Once there was a war: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Once there was a war»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Once there was a war — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Once there was a war», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Going back to the ship, the little group could not lose the sadness that Luigi had planted in it. “How would you like it to happen to your family?” Lieutenant Blank said. “Why, you can look across to Castellammare.”

On this basis the group visited the commodore in the wardroom of his flagship. They told their story and the commodore looked gravely over his coffee cup at them. And his very calm blue eyes got bright with amusement. “What do you want me to do,” he asked, “attack Castellammare?”

“No, sir,” said Lieutenant Blank. “But we have six captured Italian MS boats. How would it be if we took one of them and just went over and got her? It would only take an hour or less.”

“And suppose you lost the boat and got yourself killed?”

“We wouldn’t do that, sir. We would just run over and get her. We could do it in practically a few minutes.”

The commodore said, “I can’t permit it. The thing is out of the question. The thing is silly. We’re trying to run a war, not a maternity hospital. And besides, I have work for you to do. You can’t go running about like this.”

“Yes, sir,” said Lieutenant Blank.

“These are your orders,” said the commodore. “You are to take one of the MS boats and patrol the coast of the mainland, particularly in the area about Castellammare. You will report the presence of any German shipping there and if you see any hostile craft you will report it and engage it. It may be necessary for you to go pretty far inshore to carry out these orders. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir,” said Lieutenant Blank, “but I sure wish we could have got that girl off.”

“This is no time for sentiment,” the commodore said.

The thing was very quick. It required only to pull up to the little dock at the little town and to ask for Luigi’s daughter. In ten minutes she was at the dock carrying a bundle of clothing and, in our estimation, she was a little closer than even Luigi suspected. And then the Isotta-Fraschini engines of the MS boat purred and the white wake spread away from the boat and she cut through the water back to Capri, for MS boats do not ride on top of the water, they knife through it.

The rest was very silly. Luigi was at the waterfront and he cried and his daughter cried and about a thousand Caprianos cried and the sound of kissing was deafening and a lot of sailors looked gruff and a kind of triumphant procession went up the hill on the funicular railway and there was something in the nature of a party at Luigi’s bar. The child, no matter what its sex, is going to have Lieutenant Blank’s first name, and not only Luigi but all Luigi’s relatives are going to remember all of us in their prayers for hundreds of years to come.

So much for the assurances. But the next morning a party of five went up on the hill to get haircuts. We were sitting reading copies of The London Pictorial for 1937 and waiting for the one barber chair to be vacant when in the doorway Luigi appeared. And Luigi carried a little tray and on the tray was a Scotch and soda for each of us. And later in the day we went shopping and wherever we stopped to look and to buy there Luigi appeared with his little tray.

It was a pretty nice day.

THE CAMERA MAKES SOLDIERS

SOMEWHERE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN WAR THEATER, October 21, 1943 —

I suppose that there is no weapon which so slyly and surely attacks the souls of men as a moving-picture camera does. Men who are disgusted or hurt or just plain ignorant react to a Bell & Howell Eyemo as a frog does to a hot rock. One of our best sports writers suggested one time that the best way to get touchdowns in football was to mount a newsreel camera between the goal posts. It is a secret weapon which dissects people and brings out the curious childish ego that everyone has and lays it spread out thick on the surface.

Recently in Africa and Sicily and Italy we (not editorial we, but a cameraman and I) were working on a technical picture for the Army and there we discovered that the same force that operates at Long Island garden parties and at tennis matches also works on a battle line. It worked everywhere. Weary troops straightened up and marched stiffly and some of them tried to hog the camera and some of them looked fierce and soldierly. All shoulders went back and steps quickened. The thinly covered actor in everyone came out. A line of Army stevedores on a dock in a North African port suddenly, on seeing the camera, began to pass boxes of C-rations with a speed and rhythm which has probably never been duplicated in Army history. Of course the moment the camera was moved they went back to a much more sensible, goldbricking pace, but for the few feet of film we have, the boxes shot by and piled up in a mountain out of camera range.

The impact of the camera is by no means limited to the Americans. Our picture had to do with all kinds of work and all kinds of men. One day we set up on a barge where a number of Arabs were employed to unload cargo and, incidentally, were doing the finest bit of sleepwalking I have ever seen. Each Arab regarded each box as a personality he didn’t like, touched with reluctance, and got rid of with relief. His repugnance, however, did not make him carry it to its destination with any speed that required streamlining. With these people we did not find any speedup when the camera was produced. The moment it began to turn, every Arab stood up grandly and presented his profile and looked sternly toward Mecca. Time and time again we tried to catch them in what is called a natural pose, not of work, because that would be a contradiction in terms, but just relaxed and looking Arab. But either they had seen too many Hollywood films of Valentino as an Arab, or a Valentino had studied Arabs under the impact of the camera. We never caught them any other way except looking sternly offstage, always in profile and always noble. We had wanted to get them relaxed because I suppose Arabs have as few noble moments as anyone in the world. Bushmen may compete with them in this respect but I doubt it. And they could not be fooled. They knew when the camera was turning and when it wasn’t. They were as highly trained in stealing scenes from each other as dress extras in Hollywood. Finally we gave up. They will continue noble as far as we are concerned. We will perpetuate this myth of the noble Arab. The moment we stopped shooting they collapsed into natural Arabs, but we never got it on film.

The camera works everywhere. There is no ferocity like that on the face of a quarterback who is running, not at an opponent but at newsreel coverage on a tripod. And this may all be egotism, but there was one example of something that seemed to be much more than this. One day we set up the camera to photograph the discharge of the cargo of a hospital ship which had been loaded in Sicily. The side doors of the ship were opened and the wooden platform was extended. The lines of ambulances were drawn up on the pier, and then the stretcher-bearers came down in a steady line with the wounded men sitting and lying and huddled and stretched out in positions indicated by the nature of their wounds. Some of them were sick with pain, were gray with pain, and some were only slightly hurt so that their eyes were clear. And not one single man as he passed the camera failed to respond to it. Everyone gave it either a smile or a little nod. Some saluted it gravely. The rigid features changed and the eyes brightened, and if an arm could move it moved in greeting. I think this was not egotism. I think these men, each one of them, had a quick thought. “Someone at home will see this picture. I must appear less badly hurt than I am. Otherwise they might worry.” I think those tired smiles were a great hunk of consideration and courage.

THE STORY OF AN ELF

Интервал:

Закладка:

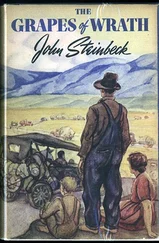

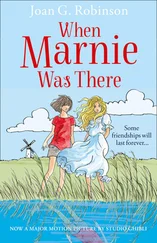

Похожие книги на «Once there was a war»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Once there was a war» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Once there was a war» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.