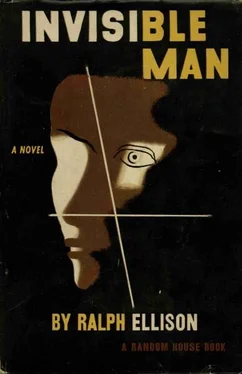

Ralph Ellison - Invisible man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ralph Ellison - Invisible man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1995, ISBN: 1995, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Invisible man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1995

- ISBN:9780679732761

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Invisible man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Invisible man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Waste Land,

Invisible man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Invisible man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The honored guests moved silently upon the platform, herded toward their high, carved chairs by Dr. Bledsoe with the decorum of a portly head waiter. Like some of the guests, he wore striped trousers and a swallow-tail coat with black-braided lapels topped by a rich ascot tie. It was his regular dress for such occasions, yet for all its elegance, he managed to make himself look humble. Somehow, his trousers inevitably bagged at the knees and the coat slouched in the shoulders. I watched him smiling at first one and then another of the guests, of whom all but one were white; and as I saw him placing his hand upon their arms, touching their backs, whispering to a tall angular-faced trustee who in turn touched his arm familiarly, I felt a shudder. I too had touched a white man today and I felt that it had been disastrous, and I realized then that he was the only one of us whom I knew -- except perhaps a barber or a nursemaid -- who could touch a white man with impunity. And I remembered too that whenever white guests came upon the platform he placed his hand upon them as though exercising a powerful magic. I watched his teeth flash as he took a white hand; then, with all seated, he went to his place at the end of the row of chairs.

Several terraces of students' faces above them, the organist, his eyes glinting at the console, was waiting with his head turned over his shoulder, and I saw Dr. Bledsoe, his eyes roaming over the audience, suddenly nod without turning his head. It was as though he had given a downbeat with an invisible baton. The organist turned and hunched his shoulders. A high cascade of sound bubbled from the organ, spreading, thick and clinging, over the chapel, slowly surging. The organist twisted and turned on his bench, with his feet flying beneath him as though dancing to rhythms totally unrelated to the decorous thunder of his organ.

And Dr. Bledsoe sat with a benign smile of inward concentration. Yet his eyes were darting swiftly, first over the rows of students, then over the section reserved for teachers, his swift glance carrying a threat for all. For he demanded that everyone attend these sessions. It was here that policy was announced in broadest rhetoric. I seemed to feel his eyes resting upon my face as he swept the section in which I sat. I looked at the guests on the platform; they sat with that alert relaxation with which they always met our upturned eyes. I wondered to which of them I might go to intercede for me with Dr. Bledsoe, but within myself I knew that there was no one.

In spite of the array of important men beside him, and despite the posture of humility and meekness which made him seem smaller than the others (although he was physically larger), Dr. Bledsoe made his presence felt by us with a far greater impact. I remembered the legend of how he had come to the college, a barefoot boy who in his fervor for education had trudged with his bundle of ragged clothing across two states. And how he was given a job feeding slop to the hogs but had made himself the best slop dispenser in the history of the school; and how the Founder had been impressed and made him his office boy. Each of us knew of his rise over years of hard work to the presidency, and each of us at some time wished that he had walked to the school or pushed a wheelbarrow or performed some other act of determination and sacrifice to attest his eagerness for knowledge. I remembered the admiration and fear he inspired in everyone on the campus; the pictures in the Negro press captioned "EDUCATOR," in type that exploded like a rifle shot, his face looking out at you with utmost confidence. To us he was more than just a president of a college. He was a leader, a "statesman" who carried our problems to those above us, even unto the White House; and in days past he had conducted the President himself about the campus. He was our leader and our magic, who kept the endowment high, the funds for scholarships plentiful and publicity moving through the channels of the press. He was our coal-black daddy of whom we were afraid.

As the organ voices died, I saw a thin brown girl arise noiselessly with the rigid control of a modern dancer, high in the upper rows of the choir, and begin to sing a cappella. She began softly, as though singing to herself of emotions of utmost privacy, a sound not addressed to the gathering, but which they overheard almost against her will. Gradually she increased its volume, until at times the voice seemed to become a disembodied force that sought to enter her, to violate her, shaking her, rocking her rhythmically, as though it had become the source of her being, rather than the fluid web of her own creation.

I saw the guests on the platform turn to look behind them, to see the thin brown girl in white choir robe standing high against the organ pipes, herself become before our eyes a pipe of contained, controlled and sublimated anguish, a thin plain face transformed by music. I could not understand the words, but only the mood, sorrowful, vague and ethereal, of the singing. It throbbed with nostalgia, regret and repentance, and I sat with a lump in my throat as she sank slowly down; not a sitting but a controlled collapsing, as though she were balancing, sustaining the simmering bubble of her final tone by some delicate rhythm of her heart's blood, or by some mystic concentration of her being, focused upon the sound through the contained liquid of her large uplifted eyes.

There was no applause, only the appreciation of a profound silence. The white guests exchanged smiles of approval. I sat thinking of the dread possibility of having to leave all this, of being expelled; imagining the return home and the rebukes of my parents. I looked out at the scene now from far back in my despair, seeing the platform and its actors as through a reversed telescope; small doll-like figures moving through some meaningless ritual. Someone up there, above the alternating moss-dry and grease-slick heads of the students rowed before me, was making announcements from a lectern on which a dim light shone. Another figure rose and led a prayer. Someone spoke. Then around me everyone was singing Lead me, lead me to a rock that is higher than I. And as though the sound contained some force more imperious than the image of the scene of which it was the living connective tissue, I was pulled back to its immediacy.

One of the guests had risen to speak. A man of striking ugliness; fat, with a bullet-head set on a short neck, with a nose much too wide for its face, upon which he wore black-lensed glasses. He had been seated next to Dr. Bledsoe, but so concerned had I been with the president that I hadn't really seen him. My eyes had focused only upon the white men and Dr. Bledsoe. So that now as he arose and crossed slowly to the center of the platform, I had the notion that part of Dr. Bledsoe had arisen and moved forward, leaving his other part smiling in the chair.

He stood before us relaxed, his white collar gleaming like a band between his black face and his dark garments, dividing his head from his body; his short arms crossed before his barrel, like a black little Buddha's. For a moment he stood with his large head lifted, as though thinking; then he began speaking, his voice round and vibrant as he told of his pleasure in being allowed to visit the school once more after many years. Having been preaching in a northern city, he had seen it last in the final days of the Founder, when Dr. Bledsoe was the "second in command." "Those were wonderful days," he droned. "Significant days. Days filled with great portent."

As he talked he made a cage of his hands by touching his fingertips, then with his small feet pressing together, he began a slow, rhythmic rocking; tilting forward on his toes until it seemed he would fall, then back on his heels, the lights catching his black-lensed glasses until it seemed that his head floated free of his body and was held close to it only by the white band of his collar. And as he tilted he talked until a rhythm was established.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Invisible man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Invisible man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Invisible man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.