"Well done," said Archie.

"Sare?"

"The steak. Not too rare, you know."

"Very good, sare."

Archie looked at the waiter closely. His tone had been subdued and sad. Of course, you don't expect a waiter to beam all over his face and give three rousing cheers simply because you have asked him to bring you a minute steak, but still there was something about Salvatore's manner that disturbed Archie. The man appeared to have the pip. Whether he was merely homesick and brooding on the lost delights of his sunny native land, or whether his trouble was more definite, could only be ascertained by enquiry. So Archie enquired.

"What's the matter, laddie?" he said sympathetically. "Something on your mind?"

"Sare?"

"I say, there seems to be something on your mind. What's the trouble?"

The waiter shrugged his shoulders, as if indicating an unwillingness to inflict his grievances on one of the tipping classes.

"Come on!" persisted Archie encouragingly. "All pals here. Barge alone, old thing, and let's have it."

Salvatore, thus admonished, proceeded in a hurried undertone—with one eye on the headwaiter—to lay bare his soul. What he said was not very coherent, but Archie could make out enough of it to gather that it was a sad story of excessive hours and insufficient pay. He mused awhile. The waiter's hard case touched him.

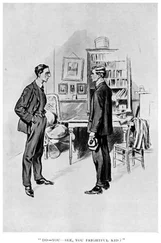

"I'll tell you what," he said at last. "When jolly old Brewster conies back to town—he's away just now—I'll take you along to him and we'll beard the old boy in his den. I'll introduce you, and you get that extract from Italian opera-off your chest which you've just been singing to me, and you'll find it'll be all right. He isn't what you might call one of my greatest admirers, but everybody says he's a square sort of cove and he'll see you aren't snootered. And now, laddie, touching the matter of that steak."

The waiter disappeared, greatly cheered, and Archie, turning, perceived that his friend Reggie van Tuyl was entering the room. He waved to him to join his table. He liked Reggie, and it also occurred to him that a man of the world like the heir of the van Tuyls, who had been popping about New York for years, might be able to give him some much-needed information on the procedure at an auction sale, a matter on which he himself was profoundly ignorant.

CHAPTER X.

DOING FATHER A BIT OF GOOD

Reggie Van Tuyl approached the table languidly, and sank down into a chair. He was a long youth with a rather subdued and deflated look, as though the burden of the van Tuyl millions was more than his frail strength could support. Most things tired him.

"I say, Reggie, old top," said Archie, "you're just the lad I wanted to see. I require the assistance of a blighter of ripe intellect. Tell me, laddie, do you know anything about sales?"

Reggie eyed him sleepily.

"Sales?"

"Auction sales."

Reggie considered.

"Well, they're sales, you know." He checked a yawn. "Auction sales, you understand."

"Yes," said Archie encouragingly. "Something—the name or something—seemed to tell me that."

"Fellows put things up for sale you know, and other fellows—other fellows go in and—and buy 'em, if you follow me."

"Yes, but what's the procedure? I mean, what do I do? That's what I'm after. I've got to buy something at Beale's this afternoon. How do I set about it?"

"Well," said Reggie, drowsily, "there are several ways of bidding, you know. You can shout, or you can nod, or you can twiddle your fingers—" The effort of concentration was too much for him. He leaned back limply in his chair. "I'll tell you what. I've nothing to do this afternoon. I'll come with you and show you."

When he entered the Art Galleries a few minutes later, Archie was glad of the moral support of even such a wobbly reed as Reggie van Tuyl. There is something about an auction room which weighs heavily upon the novice. The hushed interior was bathed in a dim, religious light; and the congregation, seated on small wooden chairs, gazed in reverent silence at the pulpit, where a gentleman of commanding presence and sparkling pince-nez was delivering a species of chant. Behind a gold curtain at the end of the room mysterious forms flitted to and fro. Archie, who had been expecting something on the lines of the New York Stock Exchange, which he had once been privileged to visit when it was in a more than usually feverish mood, found the atmosphere oppressively ecclesiastical. He sat down and looked about him. The presiding priest went on with his chant.

"Sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen—worth three hundred—sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen-sixteen—ought to bring five hundred—sixteen-sixteen-seventeen-seventeen-eighteen-eighteen nineteen-nineteen-nineteen."

He stopped and eyed the worshippers with a glittering and reproachful eye. They had, it seemed, disappointed him. His lips curled, and he waved a hand towards a grimly uncomfortable-looking chair with insecure legs and a good deal of gold paint about it. "Gentlemen! Ladies and gentlemen! You are not here to waste my time; I am not here to waste yours. Am I seriously offered nineteen dollars for this eighteenth-century chair, acknowledged to be the finest piece sold in New York for months and months? Am I—twenty? I thank you. Twenty-twenty-twenty-twenty. YOUR opportunity! Priceless. Very few extant. Twenty-five-five-five-five-thirty-thirty. Just what you are looking for. The only one in the City of New York. Thirty-five-five-five-five. Forty-forty-forty-forty-forty. Look at those legs! Back it into the light, Willie. Let the light fall on those legs!"

Willie, a sort of acolyte, manoeuvred the chair as directed. Reggie van Tuyl, who had been yawning in a hopeless sort of way, showed his first flicker of interest.

"Willie," he observed, eyeing that youth more with pity than reproach, "has a face like Jo-Jo the dog-faced boy, don't you think so?"

Archie nodded briefly. Precisely the same criticism had occurred to him.

"Forty-five-five-five-five-five," chanted the high-priest. "Once forty-five. Twice forty-five. Third and last call, forty-five. Sold at forty-five. Gentleman in the fifth row."

Archie looked up and down the row with a keen eye. He was anxious to see who had been chump enough to give forty-five dollars for such a frightful object. He became aware of the dog-faced Willie leaning towards him.

"Name, please?" said the canine one.

"Eh, what?" said Archie. "Oh, my name's Moffam, don't you know." The eyes of the multitude made him feel a little nervous "Er—glad to meet you and all that sort of rot."

"Ten dollars deposit, please," said Willie.

"I don't absolutely follow you, old bean. What is the big thought at the back of all this?"

"Ten dollars deposit on the chair."

"What chair?"

"You bid forty-five dollars for the chair."

"Me?"

"You nodded," said Willie, accusingly. "If," he went on, reasoning closely, "you didn't want to bid, why did you nod?"

Archie was embarrassed. He could, of course, have pointed out that he had merely nodded in adhesion to the statement that the other had a face like Jo-Jo the dog-faced boy; but something seemed to tell him that a purist might consider the excuse deficient in tact. He hesitated a moment, then handed over a ten-dollar bill, the price of Willie's feelings. Willie withdrew like a tiger slinking from the body of its victim.

"I say, old thing," said Archie to Reggie, "this is a bit thick, you know. No purse will stand this drain."

Reggie considered the matter. His face seemed drawn under the mental strain.

"Don't nod again," he advised. "If you aren't careful, you get into the habit of it. When you want to bid, just twiddle your fingers. Yes, that's the thing. Twiddle!"

Читать дальше