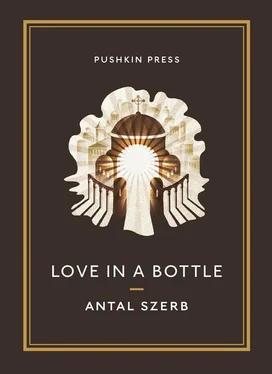

Antal Szerb - Love in a Bottle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Antal Szerb - Love in a Bottle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Pushkin Press, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love in a Bottle

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pushkin Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love in a Bottle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love in a Bottle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and

.

Love in a Bottle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love in a Bottle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We got on wonderfully well. She was so much like a colleague I almost forgot that she was such an attractive young woman, and I would have loved to take her to my bosom. I even tried to pay for her meal, despite the state of my finances. But, true to Hungarian custom, she refused so adamantly it was as if I had impugned her respectability.

The afternoon passed in what seemed a moment. How proud I felt, leading her timid steps round the catalogues and the pigeon-holes where orders were placed, and explaining the inner meaning of the pictures, all as if I personally had discovered the art of printing. I taught her everything that mattered. I pointed out the more egregious old-timers, sitting there poring over their books — the old gent with his blue cap who would stand up from time to time and whistle for a few minutes; the one who never stopped munching away; the mad one, and the talkative one who had discovered the primal human language from which all others could be derived. And when we went for coffee, I declared rather fancifully:

“Don’t let it worry you that ninety per cent of the people you see in here are geriatrics, cripples and lost souls. It’s not only an asylum for the likes of them. It’s also a refuge for the eternally young — people like you and me, for example — and in fact all human life…”

I just couldn’t find logical expression for my feelings.

But in fact Ilonka was in little need of reassurance. It was obvious on that first afternoon that she would be completely at home in the library. Perhaps this was because her sensitivity and timidity found a protective calm in the ordered, reliable, studiously innocent world that is scholarship, of which the library is the outward and visible embodiment. How comforting it is to know that everything is in its place, and all so aloof and impersonal. Moods and desires come and go, like so many restless tourists, but the folios remain in place, waiting benignly to be read by succeeding centuries. Buses, taxis and metros rush us about at frantic speed; placards bawl out every grubby little change in our material lives: the library stands for what is pure and true.

At closing time I escorted her back to the students’ hostel where she was staying.

“What are you doing after supper?” I asked.

“Nothing, really. I’ll talk to the girls for a while, then go to bed and read.”

“And the night life of Paris, doesn’t that interest you? Have you been up to Montparnasse?”

“No, and I’ve no wish to. I don’t like being with lots of other people. Besides, I couldn’t go there on my own.”

“Then come with me.”

“I couldn’t. I’ve only spoken to you for the first time today. After all.”

Her moral sense reassured me. It told me she was a proper Hungarian girl.

“Don’t you feel lonely at night? Don’t you miss your mother?”

“Not today. Today I’m really happy.”

I didn’t understand.

“Well… there’s the library. I’m so happy to be working there. And you’ve been so good to me. Will you help me again, some time?”

“But of course, gladly… I really don’t enjoy the evenings. For me, it’s the most difficult part of the day.”

I could have said a great deal more on that theme, but I didn’t want to become sentimental. She would have taken it as a way of pushing myself on her.

“I don’t want you to be sad,” she said.

We looked at one another, and were silent for some time. I’m not saying it was a deeply meaningful silence. I was listening to myself and to the muffled beatings of my soul, something not to be shared with such a young girl. For a true gentleman, loneliness is a private matter.

“Well, then,” I said, and smiled. I waited for her to say something. Then I kissed her hand and left.

I had gone a few steps along the Boulevard St Michel, still sensing the soft touch of her hand on my lips, when I had the sudden feeling that someone was following me. I turned around, and there she stood.

“Please don’t be angry. I wanted to give you this cigarette holder… you were so good to me.”

I was so surprised all I could do was grin. But before I could formulate any meaningful sentence in my head, she had slipped away, swiftly and silently, on weightless steps. The cigarette holder was one of those you can pull out to a really impressive length. I was thrilled with it, but at the same time something told me I should be asking myself why a girl who spent her days in a library should have given it to me. I filed it away as a memento of the Bibliothèque nationale. That seemed to me right and proper — due payment for scholarly services rendered. After all, I had devoted an entire afternoon to her.

After I had known her about a week, I managed to persuade her to come with me after closing time to the Rue d’Antin, to try my favourite vermouth.

There is a rather special little place in the Rue d’Antin where the only drink on offer is the Italian vermouth known as Crocefisso. The place has the sort of odd-looking door you find in English pubs — no top or bottom, just two swinging wooden boards in between to stop people looking in. This strange door seemed to create a strong impression of moral degeneracy in the girl. She recoiled from it in horror, and it took me a full quarter of an hour to persuade her to go in.

The only person inside was the old patronne , who poured the vermouth out into a long-necked glass before each of us in turn. Ilonka spent some time gazing nervously around.

“Do you come and booze here regularly?” she asked.

“Well, if by ‘boozing’ you mean dropping in occasionally with one of my friends and having a few glasses together.”

“I’m sure you’d much rather be here with your friends… Tell me, it really troubles my conscience, the amount of time you’re spending on me.”

I instantly felt an enormous tenderness towards her — the expansive, generous feeling you get when there is something you really ought to do and you actually do it.

“Truly, Ilonka, if only you knew at what a good moment you came into my life. It’s made me see just how much the library, and books, and scholarship really mean to me — and that includes the bookish life itself, with all its moments of bitterness. Because now I’ve been able to share it with you.”

She clapped her hands to her head, and her eyes took on a veiled look, as if I’d made a declaration of love. I hastened to put things right, because I believe in precision in matters of feeling.

“I think that — how can I put this? — only the selfish are beyond consolation.”

“József Eötvös,” she retorted.

“József Eötvös, indeed,” I replied, somewhat irritably. I could not help but feel the irony of her interjection, with its unstated reproach — an irony directed at the perpetual student, with his love of quotations.

“Good,” she said. “But surely I’m allowed to be grateful. Can’t you see? Before I met you I didn’t know which end of a book to pick up. I treated them like objets d’art. I’ve learnt a great deal from you.”

“Please don’t feel you owe me anything for that. I find it just as rewarding. It’s a pleasure for me too. Taking you through those books, into my personal domain, my little empire — it was almost as delightful as initiating a virgin into the secrets of love.”

She looked at me in astonishment. I had no idea where such a crude comparison could have come from, and I felt rather alarmed. But she simply nodded, and put her hand a few encouraging centimetres closer to mine on the table.

I placed mine on hers. It was very beautiful. Nature loves harmony, and the hand rarely belies the nature of the person.

However it is quite difficult to sustain a rational conversation when you are holding hands with someone. There is something intensely emotional about it, in its sheer simplicity. When a grown man takes his girl’s hand he becomes a warm-hearted apprentice boy on a Sunday afternoon outing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love in a Bottle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love in a Bottle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love in a Bottle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.