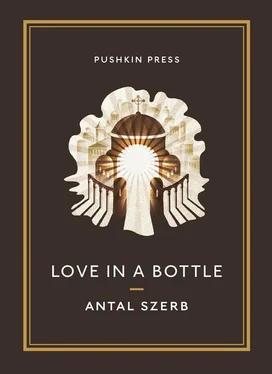

Antal Szerb - Love in a Bottle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Antal Szerb - Love in a Bottle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Pushkin Press, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love in a Bottle

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pushkin Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love in a Bottle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love in a Bottle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and

.

Love in a Bottle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love in a Bottle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And if I ever did ever mention one of my conquests, however tentatively, he would be secretly convinced that the woman in question must be a hunchback, only I had failed to notice this fact, being so caught up in my wonderful rationalising myths.

The only reason I’m telling you this is to emphasise how totally unforeseen it was, that summer evening, when Marcelle suddenly took me by the arm, after countless light years of the cosy, eunuch-like friendship in which she had so hopelessly confined me. But when I looked about myself, under the Chinese lanterns theatrically lighting the great Corot-like trees from below, with all the summer stars out in the sky above, it was a really miraculous summer night. One of those nights when dumb animals open their mouths and utter wise sayings.

Whether I had been drinking — or everyone else had — is hard to determine. A French gentleman in a hat was telling stories in which St Denis entertained his Gallic contemporaries before valiantly gathering up his decapitated head under his arm. The ugly Spanish girls around him were shrieking with laughter. I didn’t see the Spanish boys, because they had already vanished into the darkness of the shrubbery. M. Robinet was giving his magic show, with an egg, some bicarbonate of soda and the ship’s hooter with which his brother-in-law the captain had signalled the presence of his vessel as it made its way placidly along the Louvre-Suresnes, and which he had subsequently bestowed on M. Robinet during a family picnic. The famous young man gave a display of solo dancing, his legs apparently detached from the rest of his joints and twisting about in the wild rhythms with such daring that they were more like electrified trousers than actual legs. Music sounded, like a madness. Everyone was on his or her feet, and only the Alsatian waiter stayed sitting gloomily beside a large bottle of beer. But the English girls — my God, the English girls! — set aside their native cold-bloodedness and really let themselves go, the protective powder slipping from their faces and those faces becoming even more babyish than usual. There was electricity in the air, forgotten jealousies and secrets spilling out — it was another Koriandolis, where snake-like desires for other men’s women boiled over, as if everyone had staked all their emotions, heads or tails, on this one hour; and when M. Robinet in his endless benevolence extinguished the light, there seemed every possibility for sexual adventure.

On the veranda where we were sitting the darkness seemed to increase as the music fell away. It was made all the more intense by tumultuous voices coming at random from every side. How could I deny that my first action was to feel around with my hand in the blackness for Marcelle, with no particular purpose in mind but with a happy smile on my face? But Marcelle was most decidedly no longer there. I set off in frantic haste to look for her. The light might be switched on again at any time.

My hand came upon someone at random and I took her firmly by the arm. The girl I was holding said, “Ooh,” ending in the final ‘u’ of the English. I cut it short by kissing her, with uncharacteristic vigour, full on the mouth.

That kiss was an even finer instrument of self-expression than the sonnet, and at moments like this much more promising. The opening lines of the kiss said little: more important than the technical aspect was the simple joy felt in them, the joy of the mischievous adolescent and the woman’s delight in the unexpected. But the second strophe, with its daring seriousness, was already establishing a theme. In a spirit of reverence, and with a yearning that drew on my most distant memories, I paid homage to the stranger who embodied the beauty of the night, the Unknown Goddess in my arms, as the kiss proclaimed her to be through its ecstasies of pain. The third strophe concluded the theme: because I cannot see you, because I don’t know who you are — because you are Everywoman — you are the Supremely Beautiful, the She who smoulders at the base of all my passion, and my devotion to you is, like the night, eternal. But the final strophe… was no longer a strophe, and the sonnet was no more — it was nothing, simply a kiss, without duration, and I was so immersed in it, with every atom of my being, that my head spun, and I let go of that mysterious someone. When I came to again, she was no longer there, and I “thrice embraced the empty air”, as Virgil puts it so beautifully, in his Latin.

Besides, the light had suddenly come on again.

Monsieur Robinet was standing by the switch like a convivial old Satan, delighting in his guests’ damnation. The Russian Duchess grabbed the Frenchman by the shoulder and shook him:

“You’re quite mistaken,” she yelled, with a display of energy that was quite shocking. “Love can do anything. There are people out there who swim the Channel for love, and people who die in suicide pacts for love, and everyone forgives them.”

“It seems Madame is not a native of this country,” the Frenchman exclaimed, his face white with anger.

The English girls were noisily pestering a beautiful young man with a large behind, like the fantasy object of some elderly female civil servant. The Alsatian waiter had fallen asleep. But Marcelle, the perfidious Marcelle, was standing in rather intimate proximity to the famous young man. Then she sat down with him, and a few others of his kind, at a table. I turned away from them, in a whirlpool of grief.

I went over to the little Highland Scot. I was tormented by the fear that it might have been her in the darkness. It was not as if she were ugly, rather… But, even viewed from a distance, she could never have been the Unknown Goddess. Could any girl one had actually met be that? I took her by the left arm and right hand, and felt her even farther back. It hadn’t been her. Every woman’s body has a different feel in a man’s hand. Hers was not the one.

For a moment I was horrified by the thought that malicious Fate, with its love of confusion, had made me take Concepción in my arms, while she was perhaps all the while thinking of the gallant Jewish boy from Temesvár. True, I had seen her, just as the lights came on again, materialising at the far end of the veranda and sidling up, with a seductive look, to the Greek gentleman who had only half a skull — the other being made of silver (whereby, according to craniology, he must have been a martyr to previously unknown nervous disorders). But then the knowledge latent in my hands reassured me: anyone they had found beautiful could not have been Concepción.

Filled with mournful amiability I caught up with the Highland Scottish girl and declared, with stormy subjectivity, how much, ever since childhood, I had adored the Celts, the plaintive verses of Ossian and the one-eared dogs that in Ireland symbolised desire — and also that I happened to know that pen is the Gaelic word for ‘head’: something she in fact did not.

By this time I was so grief-stricken and ecstatic that I found myself not only using English with absolutely unshakeable confidence, I even felt — for some minutes — that I might do the same in Gaelic, and indeed in all manner of tongues, like the Apostles at Whitsun. I won’t go so far as to say that the girl carried boundless feminine intuition in her dear little bosom, but she looked at me like someone who realised that the tempestuous, world-annihilating possibilities I was blathering about might well have been had been imbibed along with the cognac, and the same for my tears, no doubt, and she was clearly wondering if there was any sort of Balm in Gilead for such Dadaist angst. There is indeed a balm for everything in Gilead, and not just for the torments of the School of Solemnity, and the blessed heart of the little Celtic girl found it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love in a Bottle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love in a Bottle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love in a Bottle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.