Miklós Bánffy - They Were Counted

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Miklós Bánffy - They Were Counted» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Arcadia Books Limited, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

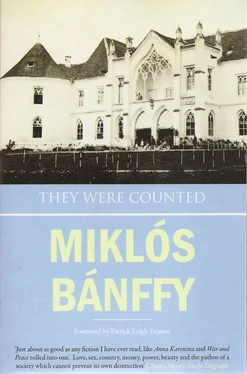

- Название:They Were Counted

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcadia Books Limited

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9781908129024

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

They Were Counted: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «They Were Counted»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

They Were Counted — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «They Were Counted», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As the old woman passed in her coach Balint thought that even then she had looked as old as she looked now and he remembered, too, many other things things that she had told him about herself or that he had been told about her by his grandfather, old Count Peter Abady, who was her first cousin.

He smiled to himself as he recalled one of her escapades.

In 1848, during the revolution, Countess Sarmasaghy, born Lizinka Kendy, was a young bride. Her husband Mihaly was a major in Gorgey’s army (everyone was a major then) fighting for Hungary’s independence and she was so much in love with him that, against all tradition, she followed the army everywhere in her carriage. She was at Vilagos when Gorgey surrendered and, ardent patriot that she was, she went immediately up to the Castle of Bohus, burst into the great hall where all the Hungarian and Russian officers were collected, brushed them aside until she faced General Gorgey and yelled at him in her sharp shrill voice ‘Governor! Sir, you are a traitor!’

Nothing had ever daunted her, and she was never afraid to say what she thought. She also had a cruel and merciless tongue. She had loathed Kossuth, and every time that his name was mentioned she would tell the story of him at the National Assembly in Debrecen. The Russians were approaching and no one knew what to do. According to Aunt Lizinka, Kossuth rose to speak and said, ‘There is no need to panic! Mihaly Sarmasaghy is on his way with thirty thousand soldiers!’ And great cheering broke out, even though Mihaly Sarmasaghy, accompanied only by his tiny wife, was actually sitting in the public gallery above. As Aunt Lizinka told the tale she made it seem that everyone knew that her courage alone equalled an untold number of fearless soldiery.

After the revolution, during which her husband had been imprisoned, it was she who handled the appropriations crisis which nearly bankrupted her husband’s family. She took their case to every court, she fought against the enforced leasing of their lands, mines and properties, and she got her husband released from his captivity at Kufstein. First she mastered all the legal intricacies of the new decrees, laws and amendments, the complications of Austro-Hungarian imperial patents, and the commercial methods of running the family mines; then she fought their case from Vasarhely to Vienna, and won.

All this Balint recalled as the old lady’s coach passed his, and this made him think, too, of his grandfather, her cousin, to whom she paid regular visits every year. He could see the two of them now, sitting together on the open veranda of the mansion at Denestornya where his grandfather had lived. Aunt Lizinka, almost submerged in her shawls and scarves, her knees pulled up, curled like a lapdog in a huge cushioned armchair; Grandfather Abady, facing his cousin in a high-backed chair, smoking cigars, as he did all day long, from a carved meerschaum holder. Aunt Lizinka would, as always, be recounting gossip about their friends, neighbours and cousins. All that Balint would understand, and remember, was his grandfather laughing ironically and saying, ‘Lizinka, I don’t believe all these evil stories: even half would be too much!’ And the old lady would declare: ‘It’s true. Every word is true. I know it!’ But the old count just smiled and shook his head, disbelieving, because even if the old countess said things that were mischievous and untrue at least she was funny when she did so.

At Denestornya Count Peter had not lived in the family castle, but in a large eighteenth-century mansion built by his own grandfather at a time when the two main branches of the Abady family had become separated and the family lands divided. The big castle had been inherited by Balint’s mother, together with three-quarters of the family estates, and it had therefore been a great event when she married Peter Abady’s son and thus reunited the family domains of Denestornya and the estates in the Upper Szamos mountains.

Count Peter had handed everything over to his son on his marriage. He kept only the mansion on the other side of the hill from the castle at Denestornya and, when his son Tamas died suddenly when still quite young, he insisted that his daughter-in-law kept the properties together and managed them. Though young Countess Abady wanted the old count to move back to the castle, he always refused; and in this he was wise, as Balint came to understand later, because although she seemed offended by his refusal, with her restless nature the good relations existing between the old count and his daughter-in-law would not have withstood the strain of living under the same roof. As it was, they kept up the old custom established when Tamas was still living: on Wednesdays Count Peter lunched at the castle, on Sundays Balint and his mother went to his grandfather’s house.

As the young Balint grew up, he often went to see Count Peter on other occasions as well. He would escape from his tutors, which was not difficult, and, as the castle park was separated from the mansion’s garden only by two low walls and the Protestant cemetery, he would pretend he was a Red Indian and sneak away silently like ‘Leather-Jerkin’ over the little wall, pretending it was a high and fearsome tower. When he arrived at his grandfather’s, the old man would notice his grubby and dust-covered clothes, but he would never ask him which way he had come or how he had got so dirty. Only if he had torn a hole in his jacket or trousers, and lest trouble should come of it, would he have the damage repaired and send a servant to unlock the park door when the boy went home.

When Balint was small, it was not his grandfather that lured the boy there; it was food. Whenever he arrived he was always given something to eat: fresh rye bread with thick sour cream, cold buffalo milk or a piece of delicious pudding from the larder. He was always hungry and up at the castle his mother had forbidden him to eat between meals. But when he grew older, it was the old man’s company that he sought. Count Peter talked to his grandson with such kindness and understanding, and listened to the tales of his pranks with a smile on his face. And he never told anyone what he had heard.

If Balint came about midday, and the weather was good, he would find Count Peter on the terrace: if it was cold he would be in the library. Though he was always reading he never seemed to mind being disturbed. Mostly he read scientific books and journals and by subscribing to so many he kept up-to-date with all the cultural movements and scientific discoveries of the times; and he would talk to his grandson about his latest enthusiasms, explaining in simple and easily understood words whatever it was that interested him the most. He seemed equally well-informed on an astonishing range of subjects, from the narratives of exploratory expeditions in Asia and Africa to advances in science and mathematics. Especially when he talked of mathematical problems he would expound them with such lucidity that when, later, Balint came to learn algebra at the Theresianum, it seemed already familiar. And these interests, fostered by his grandfather’s teaching during Balint’s surreptitious visits, remained with him long after childhood.

If he went to his grandfather’s in the morning the old count was usually to be found in his garden, where he allowed no one but himself to touch his roses. He tended them with loving care, grafting, crossing and creating new varieties. They were much more beautiful than those in the castle garden where a legion of professional gardeners were constantly at work.

On Sundays, if the boy came over early for the weekly luncheon, he would find his grandfather on the terrace talking to two or three peasants who, hat in hand, would be telling the old landowner about their problems. At such times Count Peter would indicate with a nod of his head that Balint could stay and listen but that he should sit a little to one side. People also came to ask advice from neighbouring villages or even from the mountains. Romanians or Hungarians, they knew him to be wise and just, and so they would come to him, as to their lord, to settle their problems rather than go to lawyers they could not trust. Count Abady never turned anyone away. He would sit motionless on his hard, high-backed cane chair, with his legs crossed and his trousers riding up to show his old-fashioned soft leather boots. With the familiar meerschaum cigar-holder in his mouth, he would listen in silence to their long explanations. Occasionally, he would ask a question, or intervene with a gentle but authoritative word to calm someone who showed signs of losing his temper with his opponent. This was seldom necessary because in the count’s presence everyone was on their best behaviour. He spoke Hungarian and Romanian equally fluently and his verdict was usually accepted by both parties. When all was over, whichever way the count’s judgement had gone, they would kiss his hand and go away quietly. They would also go over to Balint and kiss his hand too, as a gesture of respect, and when once Balint tried to prevent this, his grandfather told him in French to let them do it lest they should take offence, thinking he withdrew his hand in disgust.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «They Were Counted»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «They Were Counted» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «They Were Counted» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.