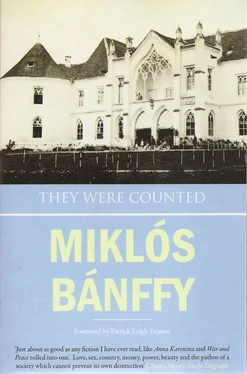

Miklós Bánffy - They Were Counted

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Miklós Bánffy - They Were Counted» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Arcadia Books Limited, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:They Were Counted

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcadia Books Limited

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9781908129024

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

They Were Counted: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «They Were Counted»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

They Were Counted — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «They Were Counted», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Is Mr Mihaly Gal at home?’ asked Balint.

The girl looked at him suspiciously. ‘What do you want him for?’

‘We just came call.’

The girl still looked uncertain. ‘Are you selling something?’ she asked, her hostility unconcealed.

‘No!’ Balint smiled. ‘We’ve just come to see him.’ To dispel her suspicions, he gave their full names and titles. The girl did not seem at all impressed. She went on with her work, crouched over the pig pail and just indicated the direction of the apple trees with her chin. ‘Over there!’ she said without ceasing to chop at the giant marrows with her knife, the slices falling messily into the swill.

Behind the little orchard and a kitchen garden, an acre and a half of vineyard climbed the hillside behind. They found the old man digging in the deep loam at the foot of the hill, shovelling and scattering the loose earth. He still had the same tall straight figure that Balint recalled from the day of his grandfather’s funeral ten years before. Though now well over ninety his bristling moustaches were still pepper and salt, darkened with wax. He was working in his shirtsleeves, boots and well-worn trousers. Balint went up and waited until the old man saw him.

‘Don’t you recognize me, Uncle Minya? It’s Balint Abady, from Denestornya.’

The patriarchal figure looked at him with eyes grown pale with age. After a brief struggle with half-forgotten memories, he seemed to recognize the grandchild of his oldest friend.

‘So you are little Balint! How you’ve grown!’ He stuck his spade in the soft earth, wiped his hands on the threadbare trousers, and clasped the young man by the shoulders. ‘How nice of you to come and see an old man! Let’s go inside.

Balint introduced his cousin and they walked slowly back towards the house, slowly but strongly, for the old man moved with assurance and held himself erect. As they passed the yard he called to the girl: ‘Julis, my dear! Bring plum brandy and glasses for the gentlemen!’

‘At once, Uncle!’ she replied and ran indoors.

‘She is my sister’s great-granddaughter,’ Minya explained, and made his visitors go before him into the living-room. It was a wide cool place whose door gave onto the portico and which was lit by the three windows overlooking the road and the flower-garden. The walls were whitewashed and it was sparsely furnished with an old rocking chair near one of the windows, a long, painted chest against one wall and in the centre of the room there was a pine-wood table with an oil lamp on it and two wooden chairs. There were simple bookshelves in one corner, with a thick black Bible among twenty or thirty tattered volumes. At the other end the bed was piled high with pillows covered in homespun cloth. The walls were bare except for an old violin, darkened with age, hanging on a nail near the foot of the bed, its bow threaded through the strings. Over a chair hung a single print in a narrow gilt frame showing a Roman knight in full armour who seemed to be making a speech.

Minya showed his guests to the table, where they sat down, and then pointed to the picture.

‘That was me,’ he said. ‘Miklos Barabas made the drawing from life. It was my last appearance.’

Balint read the inscription, ‘MIHALY GAL, illustrious member of the National Theatre, Kolozsvar, in the role of Manlius Sinister, 17 May, 1862’

‘Where did you go, after your last performance?’

‘Nowhere. I realized I couldn’t do it any more so I retired. I was no longer any good, and one shouldn’t try to force something one can’t do properly. That’s when I bought this house. I didn’t spend all my money like most actors. Perhaps if I had been more like them I’d have been better. As it was I was rotten! So I took to gardening and tending the vineyards. This I do well! Julis!’ he called to his young niece, who had just put the plum brandy on the table, ‘Bring some bunches of the ripe Burgundy grapes, you know — the ones on the left!’ Julis bustled out, and the old actor went on:

‘Anyone who tries to do what he can’t do is mad!’ Balint caught a bitter note he had never heard before. To change the subject Laszlo asked about the violin. He had noticed it as soon as they came in.

‘That old fiddle?’ answered Minya. ‘I only keep it as a souvenir. It was His Excellency Count Abady, your grandfather,’ he said, looking at Balint, ‘who gave it to me, oh, so many years ago. It must have been ’37 or ’38 — I think it was ’37. He asked me me look after it for him; but later, whenever I tried to give it back he refused. He never played again’.

Balint was astonished. He had never known that Count Peter even liked music, let alone could play. He had never spoken of it.

‘Oh, yes!’ said Minya, ‘he played beautifully. Not light stuff or gypsy music. He played Bach, Mozart and suchlike … and all from the music. He could read beautifully.’

Laszlo asked if he might look at the instrument.

‘May I take it down?’ he asked.

‘Of course!’

‘But this is a marvellous violin! It’s beautiful! Look what noble lines it has!’ He brought it to the table to inspect it more closely.

‘Yes, that is the Count’s violin. He really did play very well. He started when still at school, and I sang. I was a baritone. Oh, Lord, where did it all go? He must have studied very hard; he was a real artist. I remember when I got back to Kolozsvar — in ’37 it was because I was with Szerdahelyi then. Yes, that’s when it was. Every evening that winter, when there wasn’t a party or something, he always went to — oh, she was so lovely — he went quite secretly, and sometimes they asked me to join them, no one else, mark you, just me. They knew they could trust me not to tell.’

The old man said nothing for a moment. He bent forward, his open shirt showing the grey hairs thick as moss on his powerful chest. He reached a gnarled hand towards the violin and caressed it lightly.

Balint longed to know more about his grandfather’s past, but somehow it seemed indiscreet to ask. However Laszlo went on: ‘Did he play with a piano accompaniment?’

‘Yes, of course, with a piano, always with a piano.’

‘Who played for him?’

The dignified old actor lifted his hand in protest. He would not reveal the lady’s name then, or ever, the gesture seemed to say. Then he started to reminisce in half sentences and broken phrases, as if his tired mind and faded eyes could only catch glimpses of the past in uncertain fragments. Following his memory’s lead he was talking more to himself than to his listeners. Everything he said was confused and mixed up, complicated by a thousand seemingly irrelevant, and to the young men, incomprehensible details. He talked of other old actors, of plays and dates and though most of it meant nothing to Laszlo and Balint, it was clear that to old Minya it was all still as real as if everyone he mentioned were still alive. Throughout the scattered monologue, they sensed that he was recalling a personal drama which had nothing to do with the theatre, a real-life drama that had taken place seven decades before. But however alive this memory was, the old man never once spoke the name of the woman who had meant so much to his friend, nor even a hint as to whether she were an aristocrat or an actress. Though everyone he spoke of had been dead for many years, he still guarded the secret entrusted to him so long ago.

As he spoke they felt that he was getting near to the climax. His voice was very low:

‘How beautiful they both were! And how young — she was even younger than he, so young, so young. And then it ended. There was a concert in the Assembly Rooms … Beethoven, Chopin … Was it the music? What was it? I can see them now, they were so beautiful, a wonderful shining couple. Everybody felt it, everybody saw it! Through their playing, you could tell they belonged together. The trouble was that, everyone saw it, everyone …’ The old man frowned, ‘And, three days later it was over. I was given a letter for him — a goodbye note, though I didn’t know it then — and I had to give it to my best friend, me — of all people.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «They Were Counted»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «They Were Counted» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «They Were Counted» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.