Five in the morning. All is bathed in yellow sunlight. The air is still fresh and cool. Many tourists tear themselves out of sleep, suffer sleep deprivation, just to greet the sun. It’ll be easy for them to banish their sleepiness with a splash of cold water. It’s still cool out and you march into the hot day as into the heat of battle!

Far too few offer up their utmost to meet the day and the hour. And even the most contented heart longs for the extraordinary. Here comes the July Sunday in glaring yellow light! July Sunday, be the bearer of what we long for!

Everywhere you look, unhappy humanity is escaping. Running, exhausted, we fall in line, back to the daily grind! Monday, how sour you would be were you not the source and reason for Sunday’s sweet anticipated pleasure! On Sundays, you see the weary plunked down in meadows and woods, washed clean of last week’s filth, prepared to tackle the coming week.

As children we sat with our beloved parents evening after evening in the Stadtpark on the terrace of the Kursalon. We were served ice cream and cookie twirls and didn’t have a care in the world. For years now, father has not set foot outside his cozy room, nor mother her cozy sepulcher. Bald and careworn, I wend my way through the Stadtpark, to the terrace of the Kursalon, where I select the very same table at which we once sat so carefree with our beloved parents. I order the same flavor ice cream as I did back then, raspberry-chocolate, with plenty of crispy fresh cookie twirls. The flower bed is just as it was, perhaps a little more colorful, the arrangement a mite more original. I see parents with their children. They argue and scold. Our parents never argued and scolded — never. Maybe it was bad that they didn’t, but they had respect for their own little creations, and confidence in us too! We disappointed them; but they accepted this as their lot and our destiny. We never noticed the tears they shed over us—. Now I sit, bald-headed, careworn, in the Stadtpark, on the terrace of the Kursalon, at the very same table where we once sat without our beloved parents, eat the same dish of raspberry-chocolate ice cream as before, with plenty of crispy fresh cookie twirls—. The flower bed I look down on is a little more colorful, the arrangement a mite more original. But otherwise, nothing has changed from those days of dumb childhood to these nights of tired age! I see parents scolding their children in the park; our parents never scolded us; they hoped that we would one day repay their kindness, but we never did. We had a lovely childhood; and so we sink into memory, since the present has hardly enough substance to live on. Our parents were all too gentle, hopeful, too ready to bow to destiny. It was a curse and a blessing! For now we can look back on days that were idyllic—. Not everyone who sees the darkness closing in can look back with a thankful and loving heart on the lightness of former days—.

*

So then they all sat around him in the dear little café with the brown-yellow wallpaper and everyone, every last one of them, wanted to help, but naturally nobody had even the slightest inkling of the constant inconceivable havoc he had to endure in that ravaged brain and spinal cord (like the husk of a living corpse), his nervous system laid low by excessive use of sleeping pills (Paraldehyd), while all other organs remained, despite his 60 years, in impeccable working order. They drank tea with raspberry syrup, chocolate, coffee, they ate bread with butter, and one of them even had ham with his buttered bread. No one suspected what destruction, wrack and ruin the poet suffered, but everyone naturally tried in the most inept way to be of some assistance to this curious creature who meant so much to his friends, treasured by each on account of his own special purpose and aspirations, dreams and despair, indeed for the sum total of his own oh-so-complicated existence inscrutable to himself; everyone tried to help save the poet from sliding into the abyss, and simultaneously, to help save himself! To no avail.

He had sunk deep into the swamp of the sinful abuse of his sleeping pills, and the concern of his few true friends just slid off him like little globs of quicksilver sliding off a glass plate!

They all sat around him in the dear little café with the brown-yellow wallpaper, sipping tea with raspberry syrup, chocolate (1918!), shots of Schwechater, double malt beer etc., etc., etc., wanted to help, help, help, and yet had not the faintest notion of just how the poet was being ripped apart from inside out, a living corpse, his very essence expunged. No help is possible, no friendship, no selfless surrender, when the stubborn brain, consumed by its own sickness, almost deliberately, it seems, forsakes what could still be saved. So one by one, at irregular intervals, the friends all take their leave, deeply disappointed, and you are obliged to endure your last torments, to live through them alone! You won’t drag anyone along on life’s, nay, death’s slide into the abyss; every him, every her cuts and runs from you, the anointed one, in that last fearful hour; they can’t do anything more for you than they’ve already done! Farewell, luckless poet who gave us all the gift of his soul and did himself in with it!

Farewell!

__________________

*Published posthumously

To Make a Long Story Short:

The Prose of Peter Altenberg (

an afterword

)

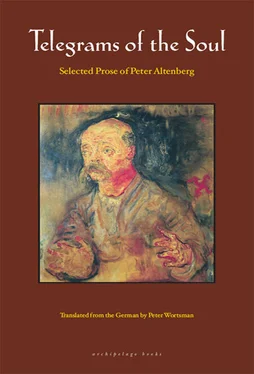

His walrus mustache was emblematic, like Walt Whitman’s wild wooly beard: no mere untrimmed tuft growing wild, but a Zeitgeist gage, a canny alley cat’s whiskers tailor-made to fit through tight fixes. And like the bewhiskered Brooklyn bard, to whom he has been compared — in stance, not style — Peter Altenberg (1859–1919), the turn-of-the-century Viennese raconteur-scribe, was a walker and a talker and an inveterate loll-about. Both had a penchant for lyrical digression and irregular punctuation, but the similarity stops there. For while Whitman went on at length in epic outbursts of freewheeling verse, Altenberg choked back the flow.

His own avowed paradigm for the pearls he spit out, most while propped up in bed in bouts of chronic insomnia, was Charles Baudelaire’s Spleen de Paris (1869). Yet whereas Baudelaire’s pioneering work comprises texts that tease and test but never forsake the playing field of poetry, Altenberg extracted the poetic essence of impressions and spat them out in spare narratives situated to the prose side of the divide.

Other formal influences include the “Correspondenzkarte,” the world’s first postcard launched and disseminated in Austria in 1869, which subsequently sparked a vogue; and the Feuilleton, a lyrical form of first person journalistic prose often of a decidedly purple slant produced by, among other Viennese wordsmiths of the day, the young Theodor Herzl before the latter forsook belles lettres for the nation-building business.

The artfully crafted fairy tales of the great Dane, Hans Christian Andersen, have been noted as yet another influence. And Altenberg’s writings can indeed be read as pruned Märchen minus the “once upon a time” and without any pretense of a “happily ever after.” “We relegated fairy tales to the realm of childhood, that exceptional, wondrous, stirring, remarkable time of life!” he wrote (in a text entitled Retrospective Introduction to My Book, Märchen des Lebens [The Fairy Tale of Life], 1908).

But why rig out childhood with it, when childhood is already sufficiently romantic and fairytale-like in and of itself?!? The disenchanted adult had best seek out the fairytale-like elements, the romanticism of each day and each hour right here and now in the hard, stern, cold fundament of life!

Читать дальше