Jerome Salinger - Nine Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jerome Salinger - Nine Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1953, Издательство: Little Brown, Жанр: Классическая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nine Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little Brown

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nine Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nine Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nine Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nine Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Really, I’m not at all—”

“Take it, for Chrissake. I didn’t poison it or anything.”

Ginnie accepted the sandwich half. “Well, thank you very much,” she said.

“It’s chicken,” he said, standing over her, watching her. “Bought it last night in a goddam delicatessen.”

“It looks very good.”

“Well, eat it, then.”

Ginnie took a bite.

“Good, huh?”

Ginnie swallowed with difficulty. “Very,” she said.

Selena’s brother nodded. He looked absently around the room, scratching the pit of his chest. “Well, I guess I better get dressed…. Jesus! There’s the bell. Take it easy, now!” He was gone.

Left alone, Ginnie looked around, without getting up, for a good place to throw out or hide the sandwich. She heard someone coming through the foyer. She put the sandwich into her polo-coat pocket.

A young man in his early thirties, neither short nor tall, came into the room. His regular features, his short haircut, the cut of his suit, the pattern of his foulard necktie gave out no really final information. He might have been on the staff, or trying to get on the staff, of a news magazine. He might have just been in a play that closed in Philadelphia. He might have been with a law firm.

“Hello,” he said, cordially, to Ginnie. “Hello.”

“Seen Franklin?” he asked.

“He’s shaving. He told me to tell you to wait for him. He’ll be right out.”

“Shaving. Good heavens.” The young man looked at his wristwatch. He then sat down in a red damask chair, crossed his legs, and put his hands to his face. As if he were generally weary, or had just undergone some form of eyestrain, he rubbed his closed eyes with the tips of his extended fingers. “This has been the most horrible morning of my entire life,” he said, removing his hands from his face. He spoke exclusively from the larynx, as if he were altogether too tired to put any diaphragm breath into his words.

“What happened?” Ginnie asked, looking at him.

“Oh… . It’s too long a story. I never bore people I haven’t known for at least a thousand years.” He stared vaguely, discontentedly, in the direction of the windows. “But I shall never again consider myself even the remotest judge of human nature. You may quote me wildly on that.”

“What happened?” Ginnie repeated.

“Oh, God. This person who’s been sharing my apartment for months and months and months—I don’t even want to talk about him…. This writer,” he added with satisfaction, probably remembering a favorite anathema from a Hemingway novel.

“What’d he do?”

“Frankly, I’d just as soon not go into details,” said the young man. He took a cigarette from his own pack, ignoring a transparent humidor on the table, and lit it with his own lighter. His hands were large. They looked neither strong nor competent nor sensitive. Yet he used them as if they had some not easily controllable aesthetic drive of their own. “I’ve made up my mind that I’m not even going to think about it. But I’m just so furious,” he said. “I mean here’s this awful little person from Altoona, Pennsylvania—or one of those places. Apparently starving to death. I’m kind and decent enough—I’m the original Good Samaritan—to take him into my apartment, this absolutely microscopic little apartment that I can hardly move around in myself. I introduce him to all my friends. Let him clutter up the whole apartment with his horrible manuscript papers, and cigarette butts, and radishes, and whatnot. Introduce him to every theatrical producer in New York. Haul his filthy shirts back and forth from the laundry. And on top of it all—” The young man broke off. “And the result of all my kindness and decency,” he went on, “is that he walks out of the house at five or six in the morning—without so much as leaving a note behind—taking with him anything and everything he can lay his filthy, dirty hands on.” He paused to drag on his cigarette, and exhaled the smoke in a thin, sibilant stream from his mouth. “I don’t want to talk about it. I really don’t.” He looked over at Ginnie. “I love your coat,” he said, already out of his chair. He crossed over and took the lapel of Ginnie’s polo coat between his fingers. “It’s lovely. It’s the first really good camel’s hair I’ve seen since the war. May I ask where you got it?”

“My mother brought it back from Nassau.”

The young man nodded thoughtfully and backed off toward his chair. “It’s one of the few places where you can get really good camel’s hair.” He sat down. “Was she there long?”

“What?” said Ginnie.

“Was your mother there long? The reason I ask is my mother was down in December. And part of January. Usually I go down with her, but this has been such a messy year I simply couldn’t get away.”

“She was down in February,” Ginnie said.

“Grand. Where did she stay? Do you know?”

“With my aunt.”

He nodded. “May I ask your name? You’re a friend of Franklin’s sister, I take it?”

“We’re in the same class,” Ginnie said, answering only his second question.

“You’re not the famous Maxine that Selena talks about, are you?”

“No,” Ginnie said.

The young man suddenly began brushing the cuffs of his trousers with the flat of his hand. “I am dog hairs from head to foot,” he said. “Mother went to Washington over the weekend and parked her beast in my apartment. It’s really quite sweet. But such nasty habits. Do you have a dog?”

“No.”

“Actually, I think it’s cruel to keep them in the city.” He stopped brushing, sat back, and looked at his wristwatch again. “I have never known that boy to be on time. We’re going to see Cocteau’s ‘Beauty and the Beast’ and it’s the one film where you really should get there on time. I mean if you don’t, the whole charm of it is gone. Have you seen it?”

“No.”

“Oh, you must! I’ve seen it eight times. It’s absolutely pure genius,” he said. “I’ve been trying to get Franklin to see it for months.” He shook his head hopelessly. “His taste. During the war, we both worked at the same horrible place, and that boy would insist on dragging me to the most impossible pictures in the world. We saw gangster pictures, Western pictures, musicals—”

“Did you work in the airplane factory, too?” Ginnie asked.

“God, yes. For years and years and years. Let’s not talk about it, please.”

“You have a bad heart, too?”

“Heavens, no. Knock wood.” He rapped the arm of his chair twice. “I have the constitution of—”

As Selena entered the room, Ginnie stood up quickly and went to meet her halfway. Selena had changed from her shorts to a dress, a fact that ordinarily would have annoyed Ginnie.

“I’m sorry to’ve kept you waiting,” Selena said insincerely, “but I had to wait for Mother to wake up…. Hello, Eric.”

“Hello, hello!”

“I don’t want the money anyway,” Ginnie said, keeping her voice down so that she was heard only by Selena.

“What?”

“I’ve been thinking. I mean you bring the tennis balls and all, all the time. I forgot about that.”

“But you said that because I didn’t have to pay for them—”

“Walk me to the door,” Ginnie said, leading the way, without saying goodbye to Eric.

“But I thought you said you were going to the movies tonight and you needed the money and all!” Selena said in the foyer.

“I’m too tired,” Ginnie said. She bent over and picked up her tennis paraphernalia. “Listen. I’ll give you a ring after dinner. Are you doing anything special tonight? Maybe I can come over.”

Selena stared and said, “O.K.”

Ginnie opened the front door and walked to the elevator. She rang the bell. “I met your brother,” she said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

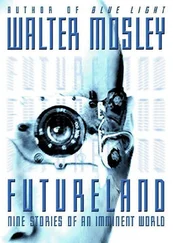

Похожие книги на «Nine Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nine Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nine Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.