Having innocently printed the MoD’s misinformation about delays to the final assault, The Times was as taken by surprise by the speed of the Argentine surrender as were MPs who had gathered in the Commons chamber expecting a ministerial progress report only to discover that the Argentines were ‘reported to be flying white flags over Port Stanley’. In the preceding hours, the MoD had insisted upon a news blackout from the South Atlantic so that no reporter could get the news of the ceasefire out before the Prime Minister had announced it to Parliament. The Times could feel a sense of vindication for the strong editorial line it had taken from the first, the leader column starting, ‘In war, only what is simple can succeed’ because ‘it was clear that it was the sheer simplicity of Britain’s immediate response to the original invasion which has sustained the operation over all these weeks and made such an historic victory possible.’ [387] ‘The Truce’, leading article, The Times , 15 June 1982.

Having initially supported the 1956 Suez fiasco, The Times had not always made the right call in such matters. Douglas-Home had risked the paper’s reputation in taking an unambiguous stance right from the beginning. Notwithstanding the loss of life, it was natural that there was a sense of relief at Gray’s Inn Road that the gamble had succeeded in its objective.

In The Winter War , the book he co-wrote with Patrick Bishop of the Observer , Witherow pointed out that the Falklands campaign was a nineteenth-century affair in the respect that it was about territory rather than ideology. Moreover, apart from the missiles, ‘the basic tools for fighting were artillery, mortars, machine guns and bayonets’, weapons that ‘would have been familiar to any veteran of World War II’. [388] John Witherow and Patrick Bishop, The Winter War , p. 17.

It thus proved to be markedly different from the British military operations of the following twenty years in which air power and technology would predetermine the outcome on the ground and Britain would be but a junior partner in an American-led coalition. Witherow maintained that Britain’s campaign was never a preordained walkover against a bunch of useless conscripts. Argentine equipment had been generally as good as that possessed by the British. Indeed, with supplies being flown into Stanley airport right up to the eve of the surrender (so much for Britain’s claim to have disabled the runway) the Argentine troops in the area were better fed and supplied than the British. What was more, they had had plenty of time to prepare defences and ‘initially out-numbered their attackers by three to one, a direct inversion of the odds that conventional military wisdom dictates. They had nothing like the logistical problems that beset their attackers.’ [389] Ibid., pp. 18, 26.

There had been moments of luck – in particular the failure of so many Argentine missiles to detonate after hitting their target – but it was undeniably a great feat of British arms. Some began to hope that it presaged an end to the long years of managing decline that had inhabited the Whitehall psyche since Suez.

The Franks Report cleared the Thatcher Government of negligence in failing to foresee the invasion but found fault with Whitehall’s capacity for ‘crisis management’. The extent to which the Government and the MoD in particular had manipulated the news coverage of the campaign rumbled on elsewhere. The Commons Defence select committee provided newspaper editors, Douglas-Home among them, with the opportunity to draw attention to the many deficiencies that MoD restrictions and poor communication links had produced. Many journalists were outraged that senior Whitehall figures like Sir Frank Cooper had consciously misled them into writing that there would be no single D-Day-style landing only hours before such an undertaking got underway. This kind of deceit undermined trust in Government information. Doubtless Sir Frank calculated that the exact veracity of a particular briefing was less important than the survival of several hundred soldiers who would be sent to their deaths if the Argentines were ready to meet the landing party. If this was the calculation then only a public servant with a peculiar set of priorities would have done otherwise. But it was a stunt that could not be repeated too often. If journalists began to disbelieve everything Government officials told them, the whole point of briefings would break down. Operational reasons were also used to justify the slow release of information. The MoD’s decision to announce that ships had been hit without naming which and the late release of casualty figures from the Bluff Cove disaster caused distress to anxious relatives and angered all those who believed news involved immediacy of information. Where the balance resided between Whitehall’s obligation to provide a free society with truthful information and its duty not to needlessly endanger servicemen’s lives could not be easily resolved.

In the twenty years following the Falklands’ campaign, the number of commercial satellites proliferated, permitting war correspondents to communicate swiftly and directly to their offices and readers or viewers. Those reporting from the South Atlantic in 1982 did not enjoy such liberty. They had no alternative but to entrust their copy to the British military who alone had the capability to transmit it back to London and, in the first instance, to the MoD censors. If the armed forces did not like the look of the copy they were under no obligation even to send the dispatch. Whitehall had been able to prevent any foreign press from covering the operation by the simple device of refusing them a berth on any of the ships travelling with the Task Force. But subsequent wars were not fought over inaccessible islands close to the Antarctic. And since they involved joint operations with allies, what reporters with one country’s troops could transmit became the effective property of all.

Indeed, the Falklands War would be the last major conflict in which newspaper reports were more immediate than television pictures. The experience of the BBC and ITV crews on the aircraft carrier Hermes was even more frustrating than that of the Fleet Street journalists on Invincible . Because the British military transmitters were at the edge of their South Atlantic coverage, satellite transmission rendered pictures of too poor a quality to show. Using commercial satellites ran supposed security risks if Argentina managed to dial in to them and gain potentially useful information. Instead, all film footage had to be flown from the Falklands to Ascension Island before it could be broadcast. This created monumental delays. The first television pictures of the landings at San Carlos were shown on British television two and a half weeks after the event. Some of the footage took twenty-three days to reach transmission. This was three days longer than it took Times readers to find out the fate of the Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854. [390] Harris, Gotcha! , p. 56.

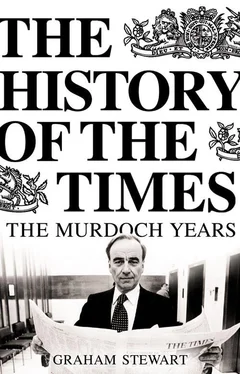

The quality of The Times ’s reporting of the Crimean War had been one of the most illustrious episodes in the paper’s history. But besides seeing its editorial line vindicated, The Times ’s coverage of the Falklands’ crisis was competent rather than remarkable. It did not, of course, want to compete with the attention-grabbing antics of the tabloids. Nonetheless, its news presentation lacked sharpness. Perhaps it was at its most deficient in its layout. Sometimes the picture selection beggared belief. The front-page headline for 3 June, ‘Argentina lost 250 men at Goose Green’, was accompanied by a photograph entitled ‘Languid lesson: Students basking in Regent’s Park, London yesterday’. The photograph that should have been used – of dejected Argentine soldiers being marched out of Goose Green into captivity – appeared on page three where there was no directly related article. Put simply, Douglas-Home had none of the visual awareness of his ousted predecessor. The magic touch of Harold Evans and his design team was noticeably lacking.

Читать дальше