Sir Gordon Brunton had got to know Murdoch through the Newspaper Publishers’ Association. The two men shared a similar attitude towards dealing with the print unions and, unlike so many of the other Fleet Street proprietors who attended NPA meetings, Brunton believed that if Murdoch gave his word on a particular action he would keep it. [22] Sir Gordon Brunton to the author, interview, 8 April 2003.

Murdoch considered Brunton ‘clear-headed and strong-willed’. [23] Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 4 August 2003.

Besides his godfather role at Times Newspapers, Sir Denis Hamilton was also chairman of Reuters, the board meetings of which Murdoch regularly attended. It was on a flight to Bahrain for one of these meetings that the two found themselves sitting together in the aeroplane. This was a seating coincidence that Hamilton – assuming Murdoch would be taking the same flight – had carefully engineered. The long flight was an unrivalled opportunity to get Murdoch alone and Hamilton did his best to, as he later put it, ‘plant as much of a seed as possible – for my fellow directors felt that only a really strong owner who would be prepared to take savage measures, and of whose determination the unions could have no doubt, had any hope’. [24] Denis Hamilton, Editor-in-Chief .

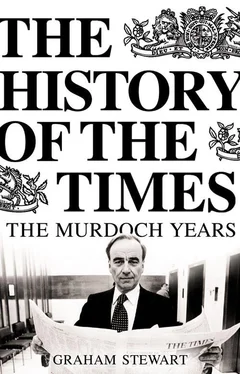

In fact, Murdoch had already scented blood. Back in September, he had bumped into Lord Thomson in the Concorde departure lounge at JFK and gained from him, however obliquely, the impression that TNL would not remain within the Thomson empire for much longer. Murdoch, indeed, had greater forewarning that The Times would be up for sale than had its editor. But whether the owner of predominately tabloid titles, a man who gave little impression of wanting to join the British Establishment, could be persuaded to take the bait and rescue The Times still remained far from clear.

Whichever projection was favoured, The Times was not on any rapid course to profitability. Although it had edged into the black during the early 1950s and for one tantalizing moment in 1977, it had been losing money for the vast majority of the twentieth century. A paper with such a track record would have been shut down long ago had it not been for its reputation and the manner in which being the proprietor of The Times conveyed a position in public life that had a value of its own. Gavin Astor, who became (alongside his father) proprietor in 1964, described the newspaper as ‘a peculiar property in that service to what it believes are the best interests of the nation is placed before the personal and financial gains of its Proprietors’. [25] Quoted in Simon Jenkins, The Market for Glory , p. 53.

But a proprietor’s belief in his role as a national custodian was not necessarily appreciated by less sentimentally minded shareholders. When Roy Thomson bought The Times in 1966 he recognized that it would not be a cash cow and, in order not to trouble shareholders’ consciences with it, opted to fund it out of his own exceptionally deep pocket. In 1974 this decision was reversed when the Thomson Organisation’s portfolio diversified further into other interests, including North Sea oil, whose profitability dwarfed TNL’s losses. The only commercial argument for retaining The Times was that as a globally recognized quality brand, it (at least psychologically) added value as the glittering flagship of the Thomson Line. Unfortunately, in becoming a byword for unseaworthiness, it risked very publicly bringing down Thomson’s reputation for business savvy and managerial skill. From that moment on, it became a matter of floating it out into the ocean and abandoning ship.

When it came to the announcement of sale, the Thomson board maintained that although they had failed, a new management team might be able to turn the paper around. This was a predictable statement – The Times could not easily be sold by asserting it had no viable future whoever owned it. But no serious forecaster believed it could be turned around quickly. Could supposedly ‘short-termist’ shareholders be expected to understand a new owner’s perseverance? In this respect Murdoch offered more hope than some potential bidders because he and his family owned a controlling share of his company, News International Limited. Thus, so long as Murdoch saw a future for the paper, News International could carry The Times through a long period of disappointing revenue without its survival in the company being frequently challenged by angry shareholders. And given the profitability of the other stallions in the stable, the Sun and the News of the World , there was every reason to expect that the banks would continue to regard News International as creditworthy.

On the other hand, appearing to have an excess of available money also threatened The Times . Journalists and print workers who regarded their paper as a rich man’s toy could be expected to want to joy ride with it. This had been part of the problem with the Thomson ownership of TNL. Roy Thomson was the son of a Toronto barber who described purchasing The Times when he was aged seventy-two as ‘the summit of a lifetime’s work’. An Anglophile, he renounced his Canadian citizenship in order to accept a British peerage (as the future Canadian proprietor of the Daily Telegraph , Conrad Black, would later do). He took as his title Lord Thomson of Fleet – the closest a peerage could decorously go towards being named after a busy street. Not only did he describe owning The Times as ‘the greatest privilege of my life’ he announced that in acquiring it, the paper’s ‘special position in the world will now be safeguarded for all time’. [26] Newsweek , 3 November 1980.

This was a hostage to fortune. Owning STV (Scottish Television) had provided much of the financial base for his British acquisitions and he had once famously described owning a British commercial television station as ‘like having your own licence to print money’. He appeared to accept that owning The Times was a licence to lose it.

Fleet Street, whose pundits were paid daily to indict others for failing to put the world to rights, was noticeably incompetent in managing its own backyard. For those proprietors already ensconced, there was at least the compensation that this created a cartel-like environment. The huge costs of producing national newspapers caused by print unions’ ability to retain superfluous jobs and resist cost-saving innovation acted to ward off all but the most determined and rich competitors from cracking into the market. Competition from foreign newspapers was, for obvious reasons, all but nonexistent. The attempts through the Newspaper Publishers’ Association to act collectively against union demands were frequently half-hearted. No sooner had the respective managements returned to their papers’ headquarters than new and deadline-threatening disputes would lead them to cobble together individual peace deals that cut across the whole strategy of collective resistance. During the 1970s, it was widely understood that one of the major newspaper groups had resorted to paying sweeteners to specific union officials who might otherwise disrupt the evening print run.

By 1980, Fleet Street’s newspapers were the only manufacturing industry left in the heart of London. The print workers came predominantly from the East End, passing on their jobs from father to son (never to daughter) with a degree of reverence for the hereditary principle rarely seen outside Burke’s Peerage or a Newmarket stud farm. They were members of one of two types of union. The craft unions, of which the National Graphical Association (NGA) was to the fore, operated the museum-worthy Linotype machines that produced the type in hot metal and set the paper. The non-craft unions, in particular NATSOPA (later amalgamated into SOGAT), did what were considered the less skilful parts of the operation and included clerical workers, cleaners and other ancillary staff. Almost any suggested change to the working practice or the evening shift would result in a complicated negotiation procedure in which management was not only at loggerheads with union officials but the officials were equally anxious to maintain or enhance whatever differential existed with their rival union prior to any change. The balance of power was summed up in a revealing and justly famous exchange. Once Roy Thomson, visiting the Sunday Times , got into a lift at Gray’s Inn Road and introduced himself to a sun-tanned employee standing next to him. ‘Hello, I’m Roy Thomson, I own this paper,’ the proprietor good-naturedly announced. The Sunday Times NATSOPA machine room official replied, ‘I’m Reg Brady and I run this paper.’ [27] Sir Gordon Brunton to the author, interview, 8 April 2003.

In 1978, the company’s management discovered that this was true.

Читать дальше