Kevin Sullivan

THE LONGEST WINTER

For Marija and Katarina with all my love

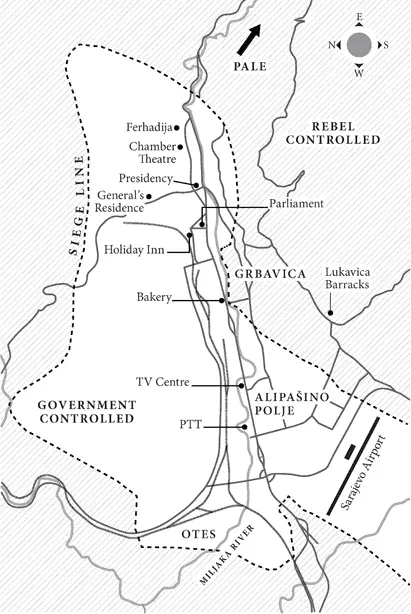

SARAJEVO, 1992–1993

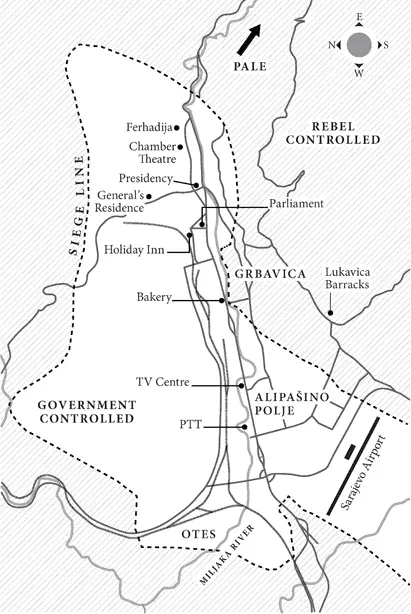

When the socialist system in Yugoslavia collapsed at the end of the Cold War, the country’s constituent republics broke away from the central government in Belgrade. Serbs and Croats formed substantial majorities in Serbia and Croatia respectively, but in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had a centuries-old tradition of diversity and multicultural tolerance, no single community enjoyed an absolute majority. Citizens of Bosnian Muslim heritage, or Bosniacs, formed the largest group, after which there were substantial numbers of Serbs and Croats, as well as Bosnians of mixed origin and other backgrounds. Family names are routinely used to attribute ‘ethnic identity’ in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and ‘ethnicity’ is used interchangeably with religious affiliation – Bosniacs are assumed to be Muslim, Croats to be Catholic and Serbs to be Orthodox. In reality there are no ethnic differences among the communities – they are all Slav – and the presumption of religious affiliation does a disservice to those who have no religious affiliation or who believe their religious practice should have nothing to do with politics.

At the start of the conflict, the government in the Bosnian capital, Sarajevo, formally adopted a policy of equal rights for all citizens regardless of which community they belonged to, while a Rebel movement with its headquarters in the ski resort of Pale, just outside Sarajevo, advocated separating the communities into homogeneous statelets. The violent creation of such statelets, with neighbours turning on neighbours, generated the ‘ethnic cleansing’ that characterised much of the conflict. The better-armed Rebels besieged Sarajevo from April 1992 until February 1996. During this siege, the longest in modern history, thousands of civilians died, including more than 1,000 children, as a result of artillery and sniper fire, and shortages of medicine and food. The United Nations deployed a force comprising troops from France and the United Kingdom as well as other countries, which was tasked with escorting humanitarian aid to vulnerable enclaves, including Sarajevo. With its limited mandate, the UN Protection Force was widely viewed as an ineffectual bystander.

This novel is set in Sarajevo during the first winter of the siege and is based on true events. For narrative purposes two of these events, the battle for control of the western suburbs and the assassination of a government minister while crossing the frontline under UN protection, are described as happening at the same time. In real life they were separated by a period of weeks.

The Luftwaffe Transall C-160 made a huge amount of noise; bits of steel and canvas webbing protruded from the metal surface of the interior amid a profusion of buttons and lights.

The three passengers were invited, one at a time, for a spell in the cockpit. Terry climbed awkwardly into a bright space that was airy and cold. The seats were upholstered with shabby and torn leather. Green webbing covered the steel partition that separated the cockpit from the main cabin, with dog-eared maps stuffed behind a matrix of elastic cord.

She looked out of the narrow windows at white clouds as the plane skirted fluffy edges of mist.

The air smelled of tobacco, steel and engine oil.

‘What’s he doing?’ Terry asked the navigator. A crew member dressed in a khaki flying suit and a yellow lifejacket stood on the other side of the cockpit peering through a side window. He held a squat pistol in his hand.

‘Missiles,’ the navigator shouted over the engine din. The navigator had a huge handlebar moustache, bulging eyes and very red cheeks. He looked like an affable drunk in a state of permanent surprise.

‘If we are targeted, he’ll fire a flare. Then we get the hell out. The missile follows the flare.’ He grinned a round beefy grin. ‘At least, that’s the theory!’

Firing flares to bamboozle missiles didn’t strike Terry as reassuringly high-tech.

There was a burst of turbulence. Terry reached out instinctively and clung to the webbing. After several seconds she felt a crewman take her arm and she allowed him to steer her back into the heaving interior where she was strapped into her seat facing a row of crates covered in heavy tarpaulin.

The other two passengers were UN logistics personnel, a man and a woman. The man, about the same age as Terry, early thirties, had introduced himself as they waited to board the plane. It had been early and cold, and his voice was rather sharp.

‘You’re a reporter?’ he asked.

‘A doctor.’

‘With which agency?’

‘The Medical Action Group, in London.’

‘I don’t know it,’ he said, in a dismissive tone of voice.

Terry would have been reassured if the man had heard of the Medical Action Group. Her own connection with the organisation was tenuous, through a friend of a friend. Yet she had agreed to take on a challenging mission on their behalf. It was a mission for which she knew she was not well prepared. The very fact that the Medical Action Group were willing to send her seemed to Terry now to count against them. Their long-standing associate, a cardiologist with extensive experience of combat medicine, had had to drop out, and they had needed a last-minute replacement. With no conflict training and no military experience, Terry was becoming increasingly conscious of being out of her depth. The bungled exchange with the UN logistics man bothered her unduly.

The man’s colleague arrived at the rendezvous breathless. She smiled a short, friendly smile and waited to be introduced to Terry, but no introductions were made. Soon after that it was time to board.

The plane flew in a giant arc, out to the coast and then south for a hundred miles before turning inward and overland again, cruising at 19,000 feet, beyond the range of anti-aircraft fire.

The noise of the engine discouraged conversation. Terry and her travelling companions sat amid the racket like bits of cargo.

When the Transall suddenly banked, the four cockpit crew leaned forward and gesticulated tentatively through the narrow windows as though they were trying to find a parking spot. The navigator pointed to the left and the others nodded vigorously. The plane began to dive.

The passengers sat in their flak jackets and stared at the boxes in front of them. Terry thought about trying to make amends for the abortive conversation with which they had begun the day. She considered a remark about the precipitate descent and the possibility of anti-aircraft fire. But, amid the scream of the plane’s fall to earth, she decided to remain silent.

* * *

‘Follow me,’ the Luftwaffe escort shouted, as the aircraft pulled up on the runway. The rear door opened and Terry saw a snaking line of white forklifts race across the tarmac towards them.

‘Let’s go!’ the escort barked. The passengers filed out obediently behind him.

The terminal was surrounded by armoured personnel carriers, forklifts and jeeps, all painted white with blue UN markings on the side. Blue-helmeted soldiers scurried in front of the long, low building. The terminal had been shelled and burned and was encased in sandbags.

Before they reached the main building the two logistics people nodded perfunctorily to Terry and the Luftwaffe officer and walked away from them towards a sandbagged hangar where the cargo from the Transall was being ferried.

Читать дальше