Alexandra Lapierre

BETWEEN LOVE AND HONOR

• TRANSLATED BY JANE LIZOP •

“He felt as though he carried within himself all that remained of the honor of men.”

—Joseph Kessel,

La Règle de l’Homme

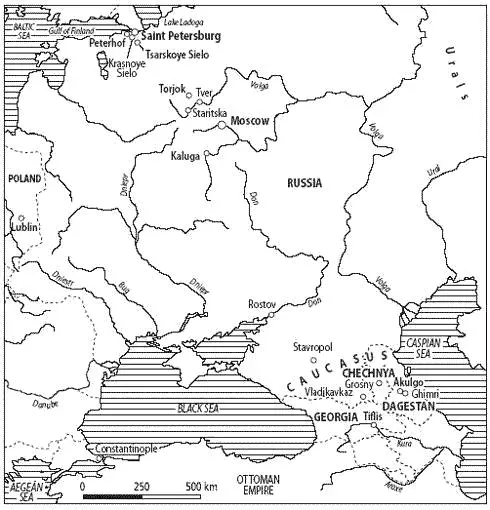

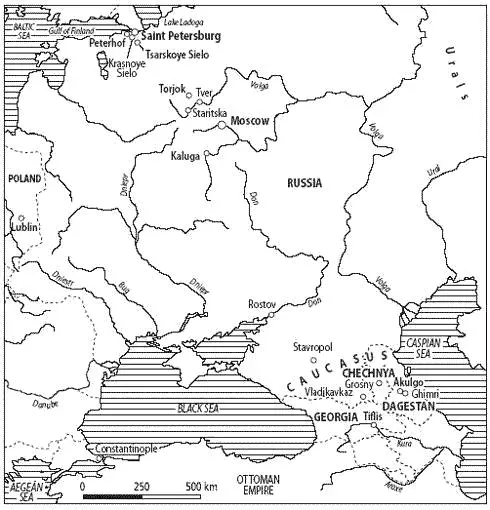

RUSSIA AND THE CAUCASUS IN THE TIME OF JAMAL EDDIN

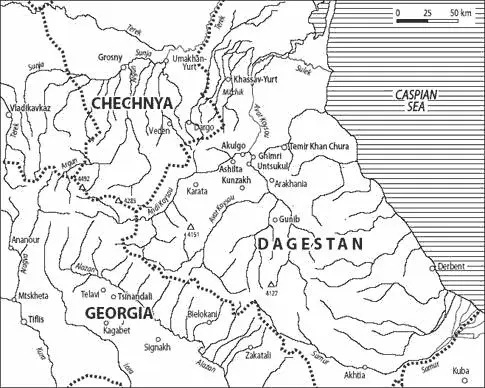

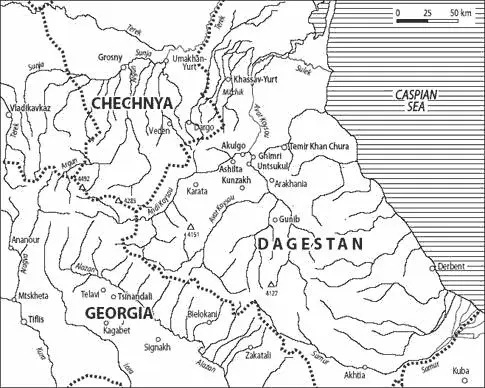

CHECHNYA, DAGESTAN, AND GEORGIA IN THE TIME OF JAMAL EDDIN

The story of Jamal Eddin Shamil, eldest son of the third imam of Dagestan and Chechnya, a man caught between two cultures, two faiths, and two loyalties, is true. I have chosen to write it as a novel in order to more fully flesh out—in dialogue, action, and sequence—the fruits of my three years of research in Russia and the Caucasus. The reader can be certain that the dates, the sequence of events, and the actions of the main characters cleave to the facts and closely follow the sources that I uncovered in the archives.

At the end of the text, the reader will find a small glossary of Caucasian terms, a list of main characters and place names, and a short bibliography.

A.L.

PROLOGUE

Not Ours, Nor Theirs

A Plain in Greater Chechnya

Thursday, March 10, 1855

As the coffin of Czar Nicholas I descends into the crypt of the Romanovs in Saint Petersburg, two groups of horsemen gather on the banks of the Mitchik River, in Chechnya.

On one side of the river stand the warriors of the imam Shamil, the Lion of Dagestan, who has been resisting the Russian invader and decimating his immense Christian army for the past thirty years. The sounds of the horses’ pawing and the clicks of loaded rifles are the only signs of his troops, most of whom are hiding among the trees of the forest, which ends abruptly at the riverbank. The imam’s personal guard stands in a row along the shore. With their long beards, shaved heads, and lambskin hats and black coats, sabers slung bandolier-style across their shoulders, and banners held at arm’s length, they are the warriors of Allah. They surround four heavy canvas-covered wagons, which reveal no sign of life within. A splendid white stallion in silver-trimmed tack, riderless, paws the gravel at the riverbank nervously. Beyond the thoroughbred and the wagons, the Caucasus Mountains rise, massively and majestically, along the horizon, toward the sky.

On the opposite bank stand the Russians. With considerable effort, their three regiments have just finished dragging their cannons to the summit of the only hillock on the plain. All of them, soldiers and officers alike, are aware that they will be advancing shortly with no cover at all. There are no bushes, not even any shadows on this side of the river, only an empty plain that descends gently to the water.

Shamil’s Muslims are in a position to fire at them at will. Indeed, the Chechen horsemen are the ones who chose this spot for the meeting, mercilessly exposing the Russian troops. In the event of an incident, they are prepared to cross the Mitchik and massacre the flower of the army of infidels.

Three generals of the Russian army—all Georgian princes—sit tall and still in their saddles on the facing hill, a fourth officer, a young lieutenant wearing the blue of the Vladimirsky Lancers, at their side. Like the three princes, the young man is looking through his binoculars to zero in on the warriors on the opposite bank, the other world. He searches for the master of this strange ceremony, the imam Shamil. The Montagnard is waiting farther up, away from his troops, seated beneath a huge black parasol. The young lieutenant sees only his shadow.

An unseasonably hot sun shines on the ragged branches of a dead fir tree, a lone tree on the Russian shore, halfway between the Muslim and Christian camps. This is where the exchange will take place.

Both armies are still. No one moves, but all are tense, ready to attack.

This morning, though, no blood must flow.

On the other side of the river, thirty-five Dagestani and Chechen Montagnards begin to ford the river, flanking the four wagons with their mysterious loads. The wagons teeter, threatening to overturn, as the wheels sink into the rocks and mud of the riverbed.

But from sandbank to islet, they manage to get across. The first wagon reaches the dead tree.

One of the imam’s horsemen breaks ranks, waving a banner to signal that the meeting may now proceed.

The princes and the young man ride down the hill.

Four abreast, they make their way across the plain, followed by their aides-de-camp and thirty-five soldiers. And by a convoy of four other wagons carrying forty thousand rubles and sixteen Chechen prisoners.

The ransom.

The two enemy groups are face-to-face, each warily watching the other’s every move.

As the princes reach the tree, they can barely make out the figures of the twenty-three women and children huddled inside before the Chechens close ranks around the enemy wagons.

They will not allow the Russians to approach the hostages. These are the princes’ wives, sisters, sons, daughters, and nieces, whom Shamil kidnapped the previous summer and has held in captivity for over eight months.

Bargaining chips.

One of the imam’s sons, a formidable warrior of twenty, pale and nervous, greets the princes with a hand held over his heart. He delivers an interminable speech in a language none of the four understand: Avar. The interpreter translates only the bits and pieces he finds essential.

“My father wants you to know that your women return to you as pure as lilies, protected from all eyes like gazelles of the desert.”

Joy, anger, and a burning desire for vengeance cross the faces of the princes, who stiffen. They nod without comment.

The lieutenant slowly leaves the Russian contingent. He guides his mount forward and bows to the imam’s son, his brother.

Without a flicker of recognition in either of their faces, Shamil’s two sons embrace. They have not seen each other in sixteen years. This cold greeting leaves them both trembling.

The Chechen horseman holding the banner presents the lieutenant with a cherkeska , the traditional uniform of the Caucasus, and asks him to put it on. The puzzled young man, who has forgotten his mother tongue, turns to the interpreter.

“The imam wants to see his eldest son dressed only in the clothing of his country,” the interpreter explains.

Dismayed, the young man protests, “How can I get undressed here, in front of everyone?”

“The wishes of the imam are law. You will learn that no one disobeys your father. No one.”

He dismounts. The Chechens press around him, forming a dense circle that hides him from the view of the others.

He cannot, must not, keep anything of his Russian past; nothing. Not his boots or spurs or epaulets. No more bright colors, no more purple and gold. One by one he undoes the buttons of his uniform and unbuckles his belt. He unties the decorative silk cords, whose copper tips glint in the sun.

Читать дальше