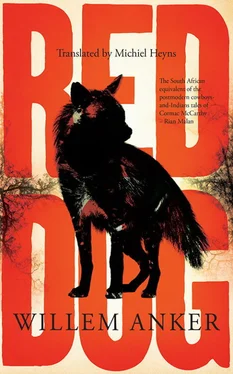

The Ngwato call me Kgowe, the first mohibidu, red man, they lay eyes on. Vyfdraai says Kgowe means To peel with a knife. My skin is sunburnt and sore, yes, I’ll grant them that. Where the hides don’t reach it does indeed look like flayed flesh. I have been stripped of skin and name. No longer white, red. No longer Coenraad, Kgowe. Whoever I am, I am at home here. For a month or so, I totally forget to rebuild the wagon. But still I want to get away, out, further. Inhambane I call my distant horizon. That far, I know by now, I’m not going to make it. But if you want to drag a whole lot of people with you into oblivion, you’d better give the nothingness a name for them to cling to.

I go hunting and overnight at a Birwa kraal. I lie with a young woman who carries on as I’ve never seen before. I let her do her thing for as long as I can hold out, which isn’t long. The next morning I can hardly get back into the saddle and she waves me good bye and her people stand staring at me sourly and silently until I’ve vanished over the ridge.

My sons start itching to trek. We hammer away at the wagon with renewed vigour until it’s standing on its own four wheels. Everything that needs to turn we lubricate with all the fat and all the oil we can find. A month later an old Caffre and the young woman and a few assegais come to visit us. The old man is her father and wants cattle from me because his daughter is pregnant. He is sent on his way with three heads of cattle and the daughter cries with joy and hugs me and I shove her away and go and pitch another damn tent.

Elizabeth is also pregnant again and full of nonsense. When she says she’s feeling flu-ish I go off to find something for my hands to do rather than listen to the whingeing. She says her head and throat are sore. Maria says Elizabeth is feverish, she must lie down flat. I leave her in the cool house to feel sorry for herself. In the blazing sun I go and make the last adjustments to the wagon.

A day later she can’t get up at all. She says she feels every muscle in her body because every one has a different kind of pain. She starts puking and shitting. The sorcerer says she has the yellow fever. I sit with her through the night and try to cool her with wet cloths. Nombini and Maria take over when I drop off to sleep. We keep her moist, but she gets hotter and hotter. What is water and what is sweat we can no longer tell. Her body is like fire in my arms and then she starts shaking with cold shivers. My wife turns yellow. I am red and she is yellow and never are we the same.

The sun is hardly up, or the wagon is loaded with Elizabeth in the back, wrapped under the softest hides and karosses. She is delirious and talks nonsense and cries and sleeps and dreams. I go to say good bye to Kgari and we hug each other and he wishes me strength. He says Come back when your wife is hale again and your son has been born and may it be a son. I say Till we meet again and here are some cattle for your trouble. I go to find Vyfdraai to tell him we’re on our way. He is nowhere to be found. Realise only then that I haven’t seen him for days. The immortal kudu has already found his own way.

The young Birwa woman comes to the wagon to say something and I don’t understand a word of it. I think she’s saying that the child’s name will be Mmegale, but what do I know and what do I care. I shout senseless nothings from the wagon that the waving people hear as farewells and we ride into the rising sun.

My Omni-head spins when I read how the missionary Wheels Willoughby is later to allege that I died of the yellow fever in the Tswapong hills. You should see those hills. It’s a piece of Eden in the midst of this wilderness. East of Palapye the world rears up, forty miles by ten. More than a thousand feet above the plains the lushness luxuriates. The mountain range is wise and silent with antiquity. They say it’s been standing like that since the Creation. The hills fold and frown with the deep and rich countenance of sandstone, quartz and iron.

I can see how my wife and I, overwhelmed with the feverish yellow and hallucination, help each other off old Glider at the foot of the hills. We fold back the dripping branches, step into the forest, clinging together to keep each other upright. I see how we’re too hot for clothes. Alone and forlorn we strip each other of our last rags. Our feet in the crevices step on the cold shards of vanished people. See how in the dusk we scrabble open antique foundries. We stoke a smoky fire with the wet branches of the trees above us. She speaks in hushed tones to her hallucinations; I snarl listless insults at mine. Fragments of copper melt anew and form rivulets among the coals. Sputtering sparks shoot up. The red-ochre drawing on the overhang lights up and cools down and vanishes. We no longer speak. We share a fever dream with resigned smiles and tears, eruptions of laughter and rolling around in the damp grass. Branches break in the thickets as buck take fright at our exuberance. A leopard calls comfortingly from its tree. In the morning we are weaker and the world hazy and who knows whether we are really seeing the parrots. Their green bellies and the yellow markings on the wings and foreheads against the lead-grey bodies. I hold my wife’s hair as she vomits against a tree. I wipe her mouth and give her water from a stream and kiss her long until overtaken by dizziness. We wake in the late afternoon with the butterflies around us. She grinds her teeth as they touch down upon her. I chase away the riot of colour from her. On the forest floor around us the wandering shadow of the spread wings of storks. We taste the waterfall on our lips before we see it. I sink down and she pulls me up. When the green curtains open, we shower together for a last time. Dassies lie in the splashes of sun on the stones. I hold my wife tight while she murmurs nonsense and hearing and seeing fade out. I wake up next to the lagoon. She is dead in my arms and cold as water, her eyes distant and clear as the river stones. The frogs are deafening, then suddenly silent. I do not get up again. The green closes in around me. My body becomes heavy and somewhere I hear a black eagle call. My mouth for a last time on her unanswering lips.

Those green hills are not granted to me. I lash the oxen to bleeding, but faster than their fastest they cannot go. Here behind me in the wagon my wife shudders with cold in the sweltering summer. Too weak to chase off the flies caking around her encrusted mouth. Next to her Maria and Nombini have fallen asleep. So many nights of caring and waking. How far away could the Portuguese be with their miraculous medicine? Arend said they were barely two days away from where he and Coenraad Wilhelm had to turn around. We should have been there by now. Where and when does this accursed continent end? Where are the boats and the breakers beyond all this dust? I must go on, forward through the red sand and thorn trees, to the trackless Portuguese, or at least the river. Any godforsaken puddle in which to bathe my wife.

The Limpopo flows wide; the hippopotami yawn. The crocodiles snap at one another with listless violence. We trek for five days along the bank and try to keep Elizabeth cool and to break the fever. She has a miscarriage. The wagon is covered in blood. I scrub the planks clean. I find clots of what could have been my child. Life drains from her through her womb. She is no longer yellow, but grey. Her scream freezes the blood of everyone except her own and then she is dead.

In the midst of the night noises of the veldt I lie on my back and look at the stars. I must have slept, because I wake up. All of creation staggers before the sun that scorches over the world. When I reach the camp Nombini offers me a bowl of water. I must have drunk it, because suddenly it is empty. I call the boys. We cover her, tamp down the soil, haul river stones and pile them on top of her.

Читать дальше