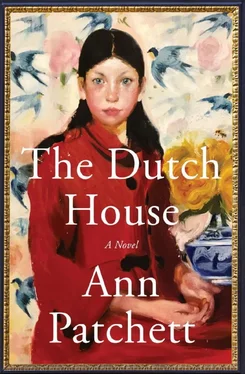

Энн Пэтчетт - The Dutch House

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Энн Пэтчетт - The Dutch House» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Dutch House

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-5266-1496-4

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Dutch House: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Dutch House»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Goodreads Choice Award Nominee for Historical Fiction (2019)

Selected as Book of the Year in The Times, Guardian, Daily Telegraph, Washington Post, Herald and Good Housekeeping.

A heart-wrenching new novel of the unbreakable bond between a brother and sister, their childhood home, and a past that will not let them go—from the Number One New York Times bestselling author of Bel Canto and Commonwealth. cite

The Dutch House — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Dutch House», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sandy and Jocelyn never talked about our mother. Never. They had saved this bomb to detonate on exactly this occasion. Andrea put her hand on the doorframe to steady herself. “Finish up,” she said in a voice without volume. “I’ll be downstairs.”

Jocelyn looked at the woman she had once worked for. “Every single day you were in this house we said to each other, ‘What could Mr. Conroy have been thinking?’ ”

“Jocelyn,” her sister said, just that one word as a warning.

But Jocelyn shook her head. “She heard me.”

Andrea’s mouth opened slightly but there were no words. She was losing herself, we could see it. She took her blows and left us to our work.

What was I thinking on that day, in that hour? Not the room I’d slept in pretty much every night of my life. Maeve said my crib had been in the corner where the couch was now, that Fluffy slept in the room with me at first so our mother could rest. I wasn’t thinking about the light that filled the room or the oak tree that brushed up against my window when it stormed. My oak tree. My window. I was thinking about getting the hell out of there and away from Andrea as quickly as possible.

We went down the wide staircase, the four of us each with a trash bag, and loaded Maeve’s car. The house was magnificent as we were walking away from it: three stories of towering windows looking down over the front lawn. The pale-yellow stucco, nearly white, was the exact color of the late afternoon clouds. The wide veranda where Andrea, wearing her champagne-colored suit, had thrown the wedding bouquet over her shoulder was the very place people stood in line to pay their respects to my father’s widow four years later. I picked up my bike and shoved it in the back of the car on top of the bags, only because I’d left it lying in the grass and all but tripped over it. Andrea was always telling my father to tell me to pick up my bike. She would tell him that when both of us were there in the room together, “Cyril, can’t you teach Danny to take better care of what you’ve given him?”

We kissed Sandy and Jocelyn goodbye. We made promises that once things were sorted out we’d all be back together, none of us understanding that we were out of the Dutch House for good. When we got in the car Maeve’s hands were shaking. She turned her purse over on the front seat and pulled open the bright yellow box where she kept her supplies. She needed to test her blood sugar. “We have to get out of here,” she said. She was starting to sweat.

I got out of the car and walked around to the other side. This was all that mattered: Maeve. Sandy and Jocelyn had already gone off in Sandy’s car. There was nobody watching us. I told Maeve to move over. She was fixing a syringe. She didn’t tell me that I didn’t know how to drive. She knew I could at least get us to Jenkintown.

The idiocy of what we took and what we left cannot be overstated. We packed up clothes and shoes I would outgrow in six months, and left behind the blanket at the foot of my bed my mother had pieced together out of her dresses. We took the books from my desk and left the pressed-glass butter dish in the kitchen that was, as far as we knew, the only thing that had made its way from that apartment in Brooklyn with our mother. I didn’t pick up a single thing of my father’s, though later I could think of a hundred things I wished I had: the watch that he always wore had been in the envelope with his wallet and ring. It had been in my hands the whole way home from the hospital and I had given it to Andrea.

Most of Maeve’s things had been sorted through and boxed up when Norma took her room, and many of those boxes had been taken to her apartment after college, as Andrea had said that Maeve was an adult now and should be a steward of her own possessions (a direct quote). Still, Maeve’s good winter coat was in the cedar closet because the summer before she’d had a problem with moths, and there were some other things—yearbooks, a couple boxes of novels she’d already read, some dolls she was saving for the daughter she was sure she would have one day, all in the attic under the eaves and behind the tiny door in the back of the third-floor bedroom closet. Did Andrea even know about that space? Maeve had shown it to the girls the night of the house tour, but would they remember or ever think to look in there again? Or would those boxes just belong to the house now, sealed into the wall like a time capsule from her youth? Maeve claimed not to care. She had all the photo albums. She had taken those with her to college. The only photo that was lost was a framed one of my father taken when he was a boy, holding a rabbit in his lap. That had somehow stayed behind in Norma’s room. Later, when we had fully realized what had happened, Maeve would be angry over the loss of my stupid scouting certificates framed on the wall, some basketball trophies, the quilt, the butter dish, the picture.

But the thing I couldn’t stop thinking about was the portrait of Maeve hanging there in the drawing room without us. How had we had forgotten her? Maeve at ten in a red coat, her eyes bright and direct, her black hair loose. The painting was as good as any of the paintings of the VanHoebeeks, but it was of Maeve, so what would Andrea do with it? Stash her in the damp basement? Throw her away? Even as my sister was right in front of me I felt like I had somehow left her behind, back in the house alone where she wouldn’t be safe.

Maeve was feeling better but I told her to go upstairs and sit down while I lugged what I had up the three flights of stairs to her apartment. There was only one bedroom and she told me to take it. I told her no.

“You’re going to take the bed,” she said, “because you’re too long for the couch and I’m not. I sleep on the couch all the time.”

I looked around her little apartment. I’d been there plenty of times but you see a place differently when you know you’re going to be living there. It was small and plain and suddenly I felt bad for her, thinking it wasn’t right that she should be in this place when I was living on VanHoebeek Street, forgetting for a minute that I wasn’t living there anymore. “Why do you sleep on the couch?”

“I fall asleep watching television,” she said, then she sat down on that couch and closed her eyes. I was afraid she was going to cry but she didn’t. Maeve wasn’t a crier. She pushed her thick black hair away from her face and looked at me. “I’m glad you’re here.”

I nodded. For a second I wondered what I would have done if Maeve hadn’t been there—gone home with Sandy or Jocelyn? Called Mr. Martin the basketball coach to see if he would have me? I would never have to know.

That night in my sister’s bed I stared at the ceiling and felt the true loss of our father. Not his money or his house, but the man I sat next to in the car. He had protected me from the world so completely that I had no idea what the world was capable of. I had never thought about him as a child. I had never asked him about the war. I had only seen him as my father, and as my father I had judged him. There was nothing to do about that now but add it to the catalog of my mistakes.

CHAPTER 7

Lawyer gooch—that was what we always called him—was our father’s contemporary and his friend, and it was as a friend he agreed to see Maeve the next day on her lunch hour. She did not agree to let me miss school to come with her. “I’m just going to get the lay of the land,” she said over cereal the next morning at her little kitchen table. “I have a feeling there will be many more opportunities for us to go together.”

Maeve dropped me off at school on her way to work. Everyone knew that my father had died and they all made a point of being nice to me. For the teachers and the coach that meant taking me aside to tell me they were there to listen, and that I could have whatever time I needed on work that was due. For my friends—Robert, who was a slightly better basketball player than I was, and T.J., who was considerably worse, and Matthew, who liked nothing more than to come to the construction sites with me—it meant something else entirely: their discomfort at my circumstances manifested itself as awkwardness, a concerted effort not to laugh at anything funny in my presence, the temporary suspension of the grief we gave one another. No grief for grief, something like that. It would never have occurred to me to pretend my father wasn’t dead, but I didn’t want anyone to know about the Dutch House. That loss was too private, shameful in a way I couldn’t understand. I still believed Maeve and Lawyer Gooch would get it all straightened out and we would be back before anyone had to know I’d been thrown out.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Dutch House»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Dutch House» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Dutch House» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Энн Пэтчетт - Прощальный фокус [litres]](/books/402782/enn-petchett-prochalnyj-fokus-litres-thumb.webp)