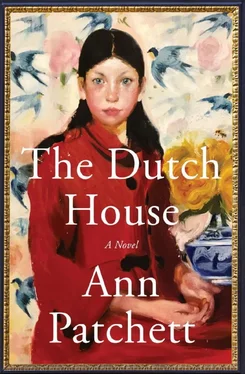

Энн Пэтчетт - The Dutch House

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Энн Пэтчетт - The Dutch House» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Dutch House

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-5266-1496-4

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Dutch House: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Dutch House»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Goodreads Choice Award Nominee for Historical Fiction (2019)

Selected as Book of the Year in The Times, Guardian, Daily Telegraph, Washington Post, Herald and Good Housekeeping.

A heart-wrenching new novel of the unbreakable bond between a brother and sister, their childhood home, and a past that will not let them go—from the Number One New York Times bestselling author of Bel Canto and Commonwealth. cite

The Dutch House — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Dutch House», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Maeve turned away from me and looked at the trees. “Thank you.”

So alone I tried to remember the good in her: Andrea laughing with Norma and Bright; Andrea coming in to check on me once in the middle of the night after I had my wisdom teeth out, her standing in the door of my room, asking if I was okay; a handful of moments early on when I saw her bring a lightness to our father, his briefly resting his hand against the small of her back. They were minuscule things, and in truth it made me tired to think of them, so I let my mind go back to the hospital, checking off the patients I would need to see tonight, preparing what I would say to them. I was back on call at seven.

CHAPTER 6

Maeve came home after she graduated, but there was never any talk of her moving back into the house. She’d scarcely been in residence since her exile to the third floor. Instead, she got herself a little apartment in Jenkintown, which was considerably cheaper than Elkins Park and not far from Immaculate Conception where we went to church. She took a job with a new company that shipped frozen vegetables. Her stated plan was to take a year or two off before going back to get her masters in economics or a law degree, but I knew she was hanging around to keep an eye on me for my last years of high school, give me something regular I could count on.

Otterson’s Frozen Vegetables didn’t know what hit them. After two months of working in the billing department, Maeve came up with a new invoice system and a new way of tracking inventory. Pretty soon she was preparing both the company’s taxes and Mr. Otterson’s personal taxes. The work was so ridiculously easy for her, and she said that’s what she wanted: a break. Maeve’s friends from Barnard were taking breaks as well, spending a year in Paris or getting married or doing an unpaid internship at the Museum of Modern Art while their fathers footed the bill for their Manhattan apartments. Maeve always had her own definition of rest.

There was something like peace in those days. I was playing varsity basketball as a sophomore, or I should say I was sitting on the varsity bench, but I was happy to be there, earning my place in the future. I had plenty of friends and so plenty of places I could go after school, including Maeve’s apartment. I wasn’t trying to avoid being home, but like every other fifteen-year-old boy I knew, I found fewer reasons to be there. Andrea and the girls seemed to exist in their own parallel universe of ballet classes and shopping trips. Their orbit had drifted so far from mine that I almost never thought about them. Sometimes I would hear Norma and Bright in Maeve’s room when I was studying. They would be laughing or fighting over a hairbrush or chasing each other up and down the stairs, but they were nothing more than sound. They never had friends over, just like Maeve and I never had friends over, or maybe they didn’t have friends. I thought of them as a single unit: Norma-and-Bright, like an advertising agency consisting of two small girls. When I got tired of hearing them I turned on my radio and closed the door.

My father had spun away as well, making my own absence a convenience for everyone. He said it was because the suburbs were booming and he had an eye towards doubling his business, and while that was true, it also seemed pretty clear he had married the wrong woman. If we all kept to our own corners it was easier for everyone. Not just easier, happier, and the house gave us plenty of space in which to carry on our individual lives. Sandy served an early dinner to Andrea and the girls in the dining room and Jocelyn saved me a plate. When I came home from basketball practice I ate, regardless of the pizza I’d already had with friends. Sometimes I would ride my bike in the dark to take sandwiches to my father at his office, and I would eat again with him. He would unroll the huge white sheaves of architectural renderings and show me what the future held. Every commercial building going up from Jenkintown to Glenside had the name conroy on a big wooden sign at the front of the construction site. Three Saturdays a month he would send me wherever I was needed—to carry lumber and hammer nails and sweep out the newly built rooms. The foundations were poured, the houses framed. I learned to walk on rafters while the regular workers, the guys who did not go home to their own mansions in Elkins Park, heckled me from below. “Better not fall there, Danny boy!” they’d call out, but once I’d learned to leap from board to board like they did, once I was talking about the electrical and the plumbing, they left me alone. I was cutting crown molding in the miter box by then. More than school or the basketball court, more than the Dutch House, I was at home on a building site. Whenever I could I’d work after school, not for the money—my father considered very few of my hours to be billable—but because I loved the smell and the noise. I loved being part of a building being made. On the first Saturday of the month, my father and I still made the rounds to collect the rents, but now we talked about scheduling the cement truck for one project while making someone else wait. There were never enough trucks, enough men, enough hours in the day for all we meant to accomplish. We talked about how far behind one project was and how another was due to come in right on time.

“The day you get your driver’s license may well be the happiest day of my life,” my father said.

“Are you sick of driving? You could teach me.”

He shook his head, his elbow pointing out the open window. “It’s a waste of time, that’s all, both of us going out. Once you’re sixteen you can collect the rent yourself.”

That’s the way it goes, I thought, admiring my own maturity. I would rather have kept the one Saturday a month with the two of us together in the car but I would take his trust instead. That was what it meant to grow up.

As it turned out, I got neither. He died when I was still fifteen.

I’m sorry to say I thought my father was old when he died. He was fifty-three. He was climbing the five flights of stairs in a nearly completed office building to check on some window flashing and caulk on the top floor that the contractor told him was leaking. The day was boiling hot, the tenth of September. The building was still a month away from having the electricity turned on, which meant no elevator and no air conditioning. There were lights rigged up in the stairwell that ran off a generator that only made it hotter. Mr. Brennan, who was the project manager, said it must have been a hundred degrees. My father complained about being out of shape when they passed the second floor, and after that he said nothing. He was never fast on account of his knee but on this day it took him twice as long. He was sweating through his suit jacket. Six steps short of his destination, he sat down without a word, threw up, and then fell straight forward, his head hitting the concrete stair, his long body following in a tumble. Mr. Brennan couldn’t catch him, but he stretched him out on the landing as best he could and ran down the stairs and across the street to a pharmacy where he told the girl at the register to call an ambulance, then he rounded up four of the men working at the site and together they carried my father down the turns of the stairs. Mr. Brennan said he had never seen a man go as white, and Mr. Brennan had been in the war.

Mr. Brennan rode along in the ambulance, and when they got to the hospital, he called Mrs. Kennedy at my father’s office. Mrs. Kennedy called Maeve. Some kid came into my geometry class and handed a folded note to the teacher, who read it to himself and then told me to get my things and go to the principal’s office. No one comes into the middle of geometry and tells you to get your things because you’re going to be a starter at the next basketball game. When I went down the hall I had only one thought and it was for Maeve. I was so sick with fear it was all I could do to make myself walk. She had run out of insulin or the insulin wasn’t any good. Too much, not enough, either way it had killed her. Until that minute I never realized the extent to which I carried this fear with me everywhere, every minute of my life. I was the tallest boy in my class, and muscled up from basketball and construction. The principal’s office was a glass-fronted room that opened onto the lobby and when I saw Maeve standing at the desk with her back to me, her unmistakable hair in a braid trailing down her back, I made a sound, something high and sharp that seemed to have come up from my knees. She turned around, everybody turned around, but I didn’t care. I had asked God for one thing and God had given it to me—my sister wasn’t dead. Maeve was crying when she put her arms around me and I didn’t even ask her. Later she would say she assumed I knew because of the look on my face, but I had no idea. I didn’t know until we got in the car and she said we were going to the hospital and that our father was dead.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Dutch House»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Dutch House» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Dutch House» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Энн Пэтчетт - Прощальный фокус [litres]](/books/402782/enn-petchett-prochalnyj-fokus-litres-thumb.webp)