‘ Nooka ,’ says Timur, taking up the oars, ‘come on then, my beauties, back to Home Sweet Home.’

We talk to Olessya about being us

As we circle back along the dusty path that leads from the lake to the gates, I see Olessya sitting in her wheelchair just behind the guardhouse. She likes to sit there on her own and look out at the people going past. No one notices her. Sometimes she’s there for hours. I’m not sure if she’ll talk to us, but she grins as we come through the gates and starts wheeling towards us.

‘Still trying to get in his pants, are you?’ jokes Masha, waving at the guard. ‘Bit young for you, even by your standards!’

‘Very funny, Masha.’ She’s still seeing Garrick, I think.

Timur gives us a nod, flicks his thumb and third finger under his ear to show he’s going off to get drunk, and walks away. Olessya turns her chair around and comes back down the drive with us to the Home entrance. It’s a warm late afternoon and none of us want to go inside, so we sit on the steps looking out across the fence at the blocks of flats opposite. A huge billboard has just gone up by the side of our road, advertising real estate in the countryside, with photos of bright new red-brick dacha country houses.

‘Looks like Amerika, doesn’t it,’ says Masha, nodding at it.

‘Remember when it was “Every Day of Labour is One More Step Towards Communism”?’ says Olessya. ‘Now it’s just buy, buy, buy.’ She looks down at the palms of her hands. ‘If you can.’

The gates to the Home swing open and the chauffeur-driven black Volga belonging to our Director, Zlata Igorovna, sweeps up the drive and parks in front of us, the engine idling, waiting to take her home. Perhaps to a dacha like the one in the billboard.

We should get back to our room to avoid meeting her, but just as we start to get up to go, the door swings open and Zlata Igorovna marches out. I shrink back, but she sees us and comes striding over.

‘So, I hear you two have been up to your usual games.’ She has this way of standing right over us. It’s what Dragomirovna and Barkov used to do. Intimidation. Power. Authority.

‘It’s in our genes, Zlata Igorovna,’ says Masha, jutting out her chin. ‘That’s what it is. Our father was an alcoholic and Dasha’s inherited his—’

‘That’s your excuse, is it?’ she interrupts sharply. ‘Everyone has an excuse, don’t they? Well, if I find out who’s bringing you vodka, I’ll fire them on the spot. And if it’s that English woman, I’ll refuse her entry.’ I nod. (It was Timur.)

‘We k-keep to our r-room,’ I say. ‘We s-stay quiet.’

‘Oh yes? And I should be grateful, should I? As if my nurses have nothing better to do than patch you up the next morning, Dasha. It’s not even as if you drink yourselves to death, more’s the pity, you just keep on going, don’t you?’ I nod again. We’re zhivoochi. Sorry about that.

She narrows her eyes at us. I don’t think she’s ever smiled in her life.

Her chauffeur has jumped out and is holding the car door open for her, so she gives us one last evil look and sweeps off.

‘So, how’s the book coming along then?’ asks Olessya once the car has driven off.

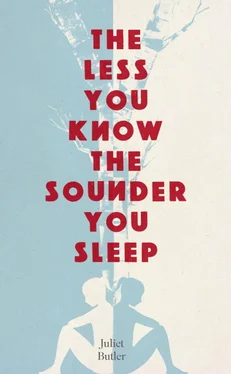

‘Good,’ I say. ‘Joolka s-seems to have got to everyone j-just in time.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They’re dying like flies,’ says Masha cheerfully. ‘Joolka wanted to ask Lydia Mikhailovna more about Anokhin, so she called up and was told she’d dropped dead. So’s Golubeva. So’s Mother Misery.’

‘Your mother?’ Olessya looks shocked. ‘She’s died?’

‘ Da-oosh . You’d better not let Joolka interview you , Olessinka. It’s like the Curse of the Book – one interview and bang! You keel over!’

Olessya looks at me and bites her lip. ‘I’m sorry, girls. About your mother.’

Masha shrugs. ‘Good riddance. Finally found her release.’

We heard about her death last week. We’d been sitting on our bed one evening when the phone rang. It’s on Masha’s side, so she always picks it up. I talk in public and she talks on the phone because only close friends have our number. She listened for a bit without saying anything, and then said: ‘No thanks,’ and put the phone down. I waited for her to tell me who it was. She picked up the controller for her Atari and turned it on. ‘That was Aunty Dina,’ she said as it started up. ‘Didn’t know she still had our number. She says Mother Misery died yesterday and did we want to go to the funeral.’ She sniffed and pressed play. I stared at her, trying to take it in. Our mother’s dead? I feel as if someone’s just kicked my leg out from under me and I’m falling… falling. Our poor, kind, sad mother who lost us twice. Mother with her soft kisses…

‘I want to go, Masha,’ I said, sitting up. ‘I want to go to the funeral. At least we can do that. Call her back and say we’re going. Where’s her number?’ I started scrabbling over her to get at our phone book.

‘Stop babbling,’ she said crossly, pushing me away from her. ‘I’m not going off to stand by her graveside in the middle of a media circus and be insulted by our darling brothers.’

‘ I want to though, I want to!’ We hadn’t seen her in over seven years, but I thought about her a lot and hoped that one day Masha would let us go and visit her. Or let her come to us. But Masha didn’t need her any more. I did, though. I didn’t know how much I needed her until the moment I heard she’d gone. ‘Call her! Call her!’

Masha slapped my face sharply.

‘ Nyet! ’

I put my hand to my stinging cheek and the tears squeezed silently out of my eyes. Just like Mother’s tears when we last saw her…

But there was nothing I could do. Nothing.

We sit here now on the steps, watching the gates closing behind Zlata’s Volga.

‘So, yes,’ continues Olessya, ‘I read the dissertation. It’s medical torture. They should be locked up.’

‘That’s too good for them,’ exclaims Masha. ‘They should be lined up against a wall and shot!’

I give a big sigh. ‘They’re dead now, most of them. They were old.’

The sun’s setting slowly over the rooftops.

Olessya shifts in her chair. ‘I didn’t realize… I think I’ve never understood fully, quite how… hard it must be, you know, to be you two.’

Masha’s about to say, ‘Try living with this shipwreck for a day…’ but strangely, she stops herself.

‘It’s not just being taken away from your parents and having those things done to you – although it did make me realize how lucky I was to have most of my childhood with my mother and father. They were kind. It’s just that after my twin and I got polio, I never saw them again. I suppose at least your mother wanted to see you when you got back in touch…’ Masha still doesn’t say anything. But she’s listening. ‘No, it was reading about how different you both were, character wise, right from the beginning. You, Masha, being so feisty and well… defiant as you grew older. Knocking down their bricks, refusing to do their so-called “games” – like being told to press that rubber bulb every time you saw a light or whatever, and throwing it down and telling them “Press it yourselves!” I laughed when I read that. And then you, Dasha, being so desperate to please, you know. Longing so much, even at that age, for approval, wanting so badly to… well, do everything they asked you to and do it well. Even if it hurt…’

We still don’t speak, me and Masha, we just watch as a visitor shows her passport to the guard at the gates and then walks slowly up the drive carrying two string bags of goods. Somebody’s daughter, I suppose.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу