‘Come in! Oh, it’s you two. OK, sit down.’ Zinaida points to a chair. She’s perched on the front of her desk, dressed in her white coat, painting her nails red. I wish I could paint my nails red too, but I keep chewing them, so they’re only stubs. Masha’s nails are long as anything. Good for scratching people in the eyes, she says.

Zinaida’s hair’s all piled up, like it’s tangled in a great big bun. Like spiders’ webs. You do it with a comb, Olessya says, pushing and pushing your hair back up so it looks all big and thick. I wish I could do that too. She reaches for a pack of Zenit cigarettes and lights one up. I don’t like the smell of smoke, but it’s better than horrible surgical spirits, which is what this clinic smells of. That just made me want to be sick when we walked in.

She’s got shiny tights, not woolly ones, and high heels. She swings one leg while she puffs smoke at us.

‘If you want another sick note, Masha, it’ll have to be cholera or leprosy you’ve got. I’m not doing ’flu any more. I know you sit on the radiators to bring your temperature up.’

‘Dysentery?’ asks Masha with her head on one side. ‘The pox?’

Zinaida looks at her watch. ‘Well, I can’t sit here wasting my time,’ she says.

‘W-we w-wanted to ask you s-something.’ She looks at me and raises a pencil eyebrow.

I can hear the first-year kids in the Hall for Extra-Curricular Activities, practising a song in English, for International Women’s Day. The window’s open, so we can hear them clear as anything. My dear, dear Mummy, I Love you Very Much. I want you to be Happy, on the eighth of March. Masha’s looking up at the ceiling and sniffing. She’s waiting for me to say it.

‘Zinaida. We’re sixteen now and w-we w-wanted to know why we’re not having a period like all the others? And C-c-can we have intimate relations? And, and, and, can we have a b-baby? Ever?’

Zinaida forgets her cigarette. It just burns down slowly while she stares at us, sticking to her red lip, in her open mouth with the ash dropping off it. The kids are still singing. Be happy, be happy, on the eighth of March!

She kind of wakes up then, and takes her cigarette out, stabbing it on the desk. Stab. Stab. She looks at us, then stabs again. Then she says:

‘Look at yourselves!’

‘There aren’t any mirrors in school,’ snaps Masha grumpily. This isn’t the answer we wanted.

‘No, I mean just look at yourselves. It’s, it’s… impossible.’

‘Why, why? What p-part’s imp-possible?’ I say.

She stands up, goes round to the back of her desk and sits down with a thump.

‘Every part. It shouldn’t even enter your head… heads.’

‘B-but why?’

‘Why? Why?! Well, if you don’t know yourselves…’

‘W-we don’t.’

‘That’s why we came to you,’ says Masha. ‘Stupid idea.’

‘W-why though, why?’ I insist, feeling Masha getting up to go. I have to know. I have to.

‘Because… because…’ She looks wildly around the room, opening and closing her mouth like a fish. ‘Because… you’d bleed to death, that’s why. That’s what would happen. And then I’d be for it, for telling you it’s all right.’

‘ Why would w-we b-bleed to d-death?’

‘I don’t know! You just can’t have sex, you can’t. You’re not… like everyone else. You can’t!’ She’s pacing around the room now, all upset. Then she comes to a stop in front of us, shakes her head and says again, but this time to me, in a low voice, ‘Look at you.’

‘Right,’ says Masha, all angry, tugging at me. ‘Thanks for that, I look at her all the time. Great advice. C’mon, you, let’s get out of here.’

She gets up then and we walk out. Masha’s furious.

‘Told you not ask,’ she says, ignoring the hoots from the gate as we cross the courtyard. ‘You and your stupid questions.’

‘What makes her think that just because we’re Defectives we can’t fall in love or feel passion and make love? That’s what she was saying, wasn’t it? Wasn’t it, Mash?’

‘She was saying we’d die if we did. That’s what she was saying, and she’s the nurse so you can stop your mooning about love right now. You wanted an answer and you got an answer.’

‘But that means I can never have sex, never have a baby…’

‘ I don’t want sex or a yobinny baby, I’ve got one hanging off my side day in, day out. I should never have given in to your nagging.’

I follow her inside, almost tripping because she’s stomping so fast, but I’m thinking that I don’t believe Zinaida. I don’t think she really knows. But if she doesn’t know, then who does?

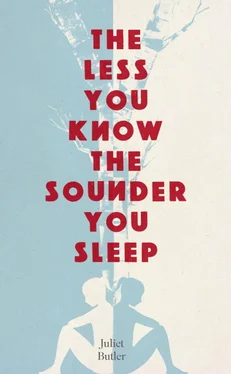

Putting up a propaganda poster on care of Defectives

I feel like screaming sometimes. No one in the world will tell us anything. No one knows anything about our parents – or if we even have them. Or if we were split in two, or were just two people who fused together somehow. Or if we’ll really die if we have sex. Someone must know.

But I won’t think about that right now. We’ve got Valentina Alexandrovna as our class teacher. Olessya’s right, she’s the best teacher in the school, she really is. Everyone thinks so, not just me. Masha does too. Me and Masha are helping her put up this banner across the whole of the school. It’s massive; it goes on forever. We’re up a ladder, putting one end up. Well, it’s sort of been put up already, but Masha said it didn’t look straight, so we’re up here straightening it. Uncle Tima, the caretaker, is nervous as a box of cockroaches. He’s standing at the bottom of the ladder with Valentina Alexandrovna, saying he’ll be fired if we fall. The banner says We Are Systematically Perfecting Forms and Methods of Social Care for Defectives. It’s a high ladder, really high actually, and I want to get down. But Masha likes taking risks. I mean, we could fall and smash our skulls, so I’m holding on and she’s banging a nail in with a hammer, but it won’t go in, so she keeps banging and banging. I really don’t think she needs to. The banner looks pretty secure to me. But she wants to, so I just don’t look down.

‘You hold on, goose, and I’ll do the man’s work,’ she says. I can’t even talk, I’m so scared, we’re so far up. I can’t even look, I really can’t. I’ll think of something else. I’m good at that.

Valentina Alexandrovna’s great. She says we can all achieve whatever we want to in life. She’s going to be our class teacher right up until we graduate. We’re her first-ever class and she’s really young for a teacher, maybe twenty? Or twenty-one? She says I can be an accountant because that’s what I want to do now. Masha wants to be a cook, and Valentina Alexandrovna says she can do that too. We’d just have to find time to do everything one by one. She says that just because crayons are broken, it doesn’t mean they can’t colour in. Actually I don’t think we’re broken. We’re just two crayons in one. With different colours each end. And then she said Communism needs every single crayon to form the Great Painting. It’s really exciting. I think I’m going to be better even than the Healthies. I really am. The Best of the Best. I’m the cleverest in class. Cleverer even than Slava now. He wants to be an accountant too. He was saying we could both be accountants on a Collective Farm in the Novocherkassk region. The same Collective Farm. That’s what he said. Masha changes her mind every week about what she wants to do. Yesterday she piped up in class and said that me and her were going to be coal miners and we’d over-fulfil all the quotas because they’d be getting two for the price of one. Everyone laughed at that, even the teacher.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу