Captain Troughton appeared, pleased to see Peter standing.

“Well done, my good and faithful! I have given Polegate to Tubbs, acting lieutenant commander, God help us all! Your boy Fanny Adams has a DSC for his performance, by the way; he certainly saved your life by dancing between the two cockpits. I have made him sub; a few weeks and he can go as a pilot. It will probably take him that long to get over his hangover – the wardroom was pleased with him and made their delight very clear. Remember that brat Kirby? He was stripped of his warrant the day after you were wounded – they had been dithering but anything you demanded was to be given that day! I had him sent to Dover as an ordinary seaman boy and he was put onto an armed drifter on the Dover Barrage. Won’t last of course – the family will be wild and pulling every string they possess. I doubt they will get him out entirely, though, and they won’t get his warrant back; can’t be done. Probably find him a shore posting of some sort. Amusing, anyway – I gather the horrible little sod is not enjoying his current existence. I have all sorts of messages from Polegate – consider them delivered. I think every man on site had something to say. You will be missed there.”

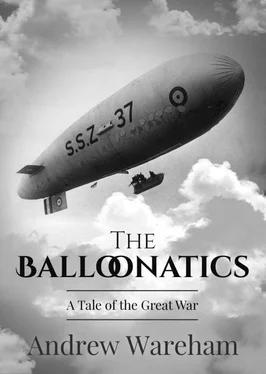

“I shall miss the balloons, sir.”

“Not ‘sir’, old chap. Two post captains together are we.”

“Crazy, is it not, Archie!”

“Just so, Peter. Hush, now. I hear vehicles outside. Can you stand for another ten minutes?”

“Probably. Catch me if I fall.”

On the second of eleven o’clock there was a great scurry and flurry as the doors were flung open and a party of dignitaries appeared, uniforms shining bright with braid and medals, the civilians in old-fashioned frockcoats and top hats.

“His Majesty the King!”

Civilians disappeared into bows and curtseys while the uniformed stiffened to attention, Peter doing his best.

Troughton made the presentation.

“Captain Naseby, Your Majesty.”

“Thank you. How do you feel, Captain Naseby? A silly question to a man who has just lost a foot! I hope you will soon be more the thing.”

“Thank you, Your Majesty. A few weeks and I shall be rid of these crutches and walking freely again.”

“Well done, sir. You are brave indeed, as we all know. Decorated twice for gallantry within a very few months and promoted rapidly. A pity that you can no longer serve in the Navy, sir.”

“I am to work in the new oil industry, Your Majesty. I believe there will be a deal for me to do there.”

The King had obviously never heard of such a thing, gave it his grave approval.

“So there will. I have no doubt you will do much to make Britain a world leader in the field. I shall look forward to hearing of your achievements over the years. For now, I have the greatest of pleasure in awarding you my grandmother’s medal for gallantry, the Victoria Cross, Captain Naseby. The citation makes it clear that you placed the demands of duty in front of your own life, sir. I am proud that you are one of my subjects, sir.”

Peter had not noticed the little hook on the breast of his uniform, was startled, his amazement showing from the ripple of laughter among the watchers.

“Your Majesty!”

The King stepped back and was introduced to matron and senior doctors of the hospital before being taken away.

The Press descended.

Being wounded, they demanded fewer poses for photographs and permitted him to sit for questioning. He took pains to play up the role of Midshipman Adams, bravely tending to his pilot in mid-air, saving his life with his bandaging; anything to lessen the idiocy he was faced with.

“What next for you, sir?”

“Civilian life, obviously. I cannot serve without a foot. I do not doubt that I shall be able to find a useful occupation, building our nation’s industrial might to fight this war.”

“Have you considered a political career, sir?”

“No.”

There were a few, well-hidden grins. Very few of the war heroes they talked to ever seemed to want to be politicians.

“When will we win this war, sir?”

A malicious question with a sting in the tail. He spotted Troughton’s frown, thought quickly.

“We are fighting a determined, militaristic enemy. Ours is a peace-loving country and it must take us time to turn our hands to the war Germany wanted. We are not Prussians and must be thankful for it!”

That, he thought, was as meaningless an answer as the question deserved. Several of the reporters were grinning openly as they went away.

“What was that about, Archie?”

“The Daily Mail is backing General Haig to take over from Sir John French. A headline to the effect that our latest VC thinks the war is not being prosecuted as it should be would be another blade in French’s back. As it stands, they have nothing from you that will aid their cause. Well thought, by the way – you need to be quick on your feet when those bastards are about!” He stopped for a second, face showing shocked. “I’m so terribly sorry, old chap! That must be as tactless as I have ever managed!”

“What?”

“Bloody hell – you might at least have noticed when I put my foot in my mouth! Oh, Christ! Did it again! I said you need to be ‘quick on your feet’.”

“Oh! So you did. Not something I shall ever be again. It don’t matter at all, Archie – I am not to go looking for slights and demanding extremities of tact from all who come into contact with me.”

“No. Even so, it was unnecessary on my part. What are you doing next, do you know? You can’t remain with us in the Andrew – the days of pegleg sea captains are gone. There are other possibilities, you know. Intelligence are always looking for bright young men to man their desks.”

“Bugger them! Not my cup of tea, Archie. Talking of which, is that refreshments I see?”

He spent the next five minutes discovering that it is almost impossible to manage a teacup on crutches, came close to losing his temper.

“A third hand would be useful, Peter. Not to worry. Here. If you stand by the table, all will be well. Better still if you sat down, you must have been on your feet long enough.”

It was sensible advice. He forced himself to welcome it.

Next morning saw him at home and faced with the problem of stairs. Trying to achieve something he had never thought about before was annoying, again. He had a choice, he suspected, of simply facing a series of challenges or of becoming a bad-tempered, whining invalid. He climbed the stairs.

He called for a taxi on the Monday and made his way to the premises of the sole motor showroom in the town, unprosperous and on the verge of closing its doors under wartime restrictions on petrol usage. People were not buying cars.

“A vehicle to be modified for a driver with a single foot, sir? Oh, I should think we could rise to that problem, sir. It is not, sad to say, unprecedented in our country. Too many young men have come home to stay in a sad condition!”

The salesman was well into his forties and saw no prospect of being called to the war, had a vast wealth of sympathy for those less fortunate than him.

“We must retain a clutch, operated by the foot. A hand throttle is simple enough. The brake to be operated like that on a motor cycle and we have solved the entire problem, sir. A car with a larger engine, one that does not require the double declutch, will make the driver’s life simpler.”

And substantially more expensive, Peter did not doubt. He had driven a car, was sure that he could master the relatively minor change demanded of him. They discussed models, settling on the Lanchester that happened to be the most costly vehicle in the showroom.

“Four weeks, I am afraid, to make the modifications, sir. They must be done at the factory.”

Читать дальше