“No,” I said, more sharply than I intended. Everyone knew what clothes like Margaret’s meant. Paul called the women who slept with Soldaten “stuffed mattresses.” But perhaps I was being unfair. She’d always had beautiful clothing—I’d worn many of her things myself. The new ensemble wasn’t necessarily from her lover.

“What did I miss?” she asked.

“They say the Allies will get here any day!”

I expected her to be thrilled like the rest of us, but she merely said, “Oh.”

Bitsi came to say hello, my grandmother’s pearly opal on her finger. When my parents had discussed giving the heirloom to Bitsi, I insisted. I wanted her to have it, to know we considered her family. I’d even showed her Rémy’s and my secret place. Among the crumpled handkerchiefs and dust bunnies, we lay together, me clutching his toy soldier, she his favorite book, Of Mice and Men . I’d grown up believing that love lasted until a mistress tore a couple apart, but Bitsi had proven that not even death could destroy true love. In that dark womb, we sobbed, our tears welding us together as sisters more than any wedding ever could.

I’d received a letter from one of Rémy’s friends and handed it to Bitsi to read.

Dear Odile,

We called your brother “Judge” because he’s the one we went to to settle our disputes. I even fashioned him a gavel with a rock, twig, and a length of twine. Stuck here, far from home, we’re frustrated and angry. Bored and hungry. Don’t take much to set someone off. “Judge,” I’d say, “is your court in session? Louis won’t stop taking the Lord’s name in vain. It tears Jean-Charles up, and he done tore into Louis.” Our arguments may seem petty, but the Judge took each one seriously and managed to soothe men who’d reached the end of a frazzled rope. We miss him.

Faithfully yours,

Marcel Danez

Seeing Bitsi’s expression brighten as she read, I insisted that she keep the letter. Marcel’s tribute meant the world to me, but she meant more. She held the scrap of paper to her heart and made her way to the children’s room.

Watching her go, Margaret hissed, “That hair of hers resembles a crown of thorns! Little Bitsi will tire of the role of weepy widow, and take a beau.”

Her insinuation—that Bitsi’s grief for Rémy was an act—hit me like a fist. I couldn’t bear that idea that Bitsi would forget my brother. My chest hurt so much I could barely breathe. I rushed from the room. If I’d slowed down, if I’d stopped to think, I would have remembered a time when Bitsi’s virtue had made me feel tarnished, too; Margaret’s scorn was less about Bitsi and more about her own shame.

When Boris saw me leave, he said, “Are you sure about leaving Margaret on her own in the reference room?”

“Believe me, she thinks she has all the answers!”

“She’s been a good friend to you and the Library.”

“Why are you taking her side?”

He winced. “Just go.”

I needed to talk to someone who understood. At the precinct, Paul offered me his chair.

“You wouldn’t believe what Margaret said.”

“It’s the war. We all say—and do—things we regret.” He rarely referred to the past. My refusal to deliver books that one time. His arrest of Professor Cohen. The way we’d romped in the sheets of the departed. It was the only way we could continue as a couple.

“I know.”

“Life will go back to normal.”

“We’ve said that for years. What if this is normal?”

“Nothing lasts forever,” he said, gently massaging my back.

“Last week, when I told Margaret that Maman went to the butcher’s at dawn, and there were already ten housewives in line, she said, ‘Why doesn’t she buy from the black market?’ With what money, I’d like to know. Anyway, all her food comes from Fe—”

I stopped myself. No, no, no, you always do this. Not this time. Keep your mouth shut!

“What were you going to say?” he asked.

I exhaled. “Nothing.”

“Margaret’s a nice type,” Paul said, “for an English girl, I mean.”

“Nice? She insinuated that Bitsi was pretending to mourn.”

“People speak without thinking. I’m sure she didn’t mean any harm.”

He wouldn’t rush to defend her if he knew about her Nazi. Margaret had it easy. All she had to do was snap her bony fingers, and she had parties, couture, jewelry, and trips to the seaside.

“She insinuated that Bitsi will take a lover.”

“Of course, Bitsi will always love your brother, but maybe someday—”

“Maybe someday?” I said sharply. “She’ll never forget Rémy. Never! Not everyone’s a slut like Margaret.”

Paul’s hands stilled on my shoulders. “You don’t mean that.”

How could he believe the worst of Bitsi, but the best of Margaret?

“You don’t mean that,” he said again.

I turned to face him and took cruel pleasure in saying, “She has a German lover.”

My claim floated in the air between us, the space of a breath.

Paul’s lips curled in distaste. “Slut!”

With his echo of my word, I realized I’d let my temper get the best of me. I had to be more careful and less judgmental.

“I shouldn’t have said what I did. You were right, you always are. She’s nice, so good to my family. Thanks to her, Rémy always had food. At the Library, I don’t know what we’d do without her. She’s there now, doing my job.”

“Harlots like her will get what’s coming to them.”

“Please don’t talk like that. Her husband’s a cad. She deserves better. You’re right, people speak without thinking, like I did just now. Please promise you won’t tell.”

Paul remained silent.

“You won’t say anything, right?”

“Who would I tell?” He turned me around and continued to massage my shoulders, his fingers digging in harder this time.

CHAPTER 41

Odile

IN PARIS, GAS LINES had been cut and almost no one had power, yet there was a certain electricity in the air. Posters pasted on the sides of buildings urged Parisians to “attack the enemy wherever he might be.” The police went on strike, as did railway employees, nurses, postmen, and steelworkers. Paul helped dig up cobblestones and create barricades, anything to trap and ambush the enemy.

Combat was something I’d read about, something that happened far away, but now I heard shots in nearby streets, and people were setting cars and tanks on fire. Rumors ricocheted like bullets. It was the Americans come to liberate us! No, it was de Gaulle! No, Parisians had had enough and were fighting back! The Germans were retreating! No, they weren’t giving up without a fight!

Going to and from work, I crept along the sides of the buildings, scared of snipers, scared of bombs, scared nothing would change and we would live like this forever.

On the evening of the twenty-fourth, as I tried to finish Voyage in the Dark before what was left of the candle flickered one last time and went out, the church bells in Paris rang. I rose and met my parents in the hall. In her dressing gown, Maman looked to the heavens, as if to marvel at God’s miracle. Papa held out his arms, the way he used to when Rémy and I were little and we’d gallop toward him. I knew my parents and I were thinking the same thing—if only Rémy were here. Wordlessly, we embraced, knowing the Occupation was at an end.

PARIS HAD BEEN liberated. Mr. Pryce-Jones limped through the Library, shouting, “The Germans have fled.” Close on his heels, M. de Nerciat exclaimed, “We’re free!” After kissing me on the cheeks, the two men embraced, then quickly stepped apart. They were the only discreet ones. I hugged Bitsi, Boris, and the Countess. Her servants brought over all the champagne left in her cellar. I drank more in one day than I had in my entire life.

Читать дальше

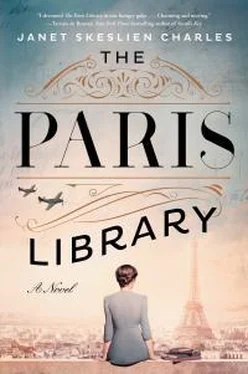

![Джанет Скеслин Чарльз - Библиотека в Париже [litres]](/books/391555/dzhanet-skeslin-charlz-biblioteka-v-parizhe-litres-thumb.webp)