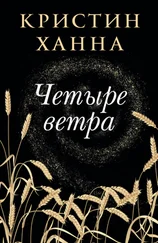

And then the rains slowed and never started up again. Drought.

These days, green fields were a distant memory, a mirage of her youth. The adults looked as parched as the ground. Grandpa spent hours standing in his dead wheat fields, scooping the dry earth into his callused hands, watching it fall away through his fingers. He grieved for his dying grapes and told anyone who would listen that he’d brought the first vines from Italy, stuffed in his pockets. Grandma had built altars everywhere, doubled the number of crucifixes on the walls, and made them all pray for rain each Sunday. Sometimes the whole town came together in the schoolhouse to pray for rain. All different religions begging God for moisture: the Presbyterians, the Baptists, the Irish and the Italian Catholics, each in their own rows. The Mexicans had their own church built hundreds of years ago.

Everyone talked about the drought constantly and missed the good old days. Except her mother.

Loreda sighed heavily.

Had there ever been any fun in her mother? If so, it was another of Loreda’s lost memories. Sometimes, when she lay in bed, drifting toward sleep, she thought she remembered the sound of her mother’s laughter, the feel of her touch, even a whispered, Be brave, just before a good-night kiss.

More and more, though, those memories felt manufactured, false. She couldn’t remember the last time her mother laughed about anything.

All Mom did was work.

Work, work, work. As if that would save them.

Loreda couldn’t remember when exactly she’d begun to be angered by her mother’s … disappearance. There was no other word for it. Her mother rose well before the sun and worked. Day after day. Hour after hour. She harped constantly about saving food and not dirtying clothes and not wasting water.

Loreda couldn’t imagine how her handsome, charming, funny father had ever fallen in love with Mom. Loreda had once told her father that Mom seemed afraid of laughter. He had said, “Now, Lolo,” in that way of his, with his head cocked and a smile that meant he wouldn’t talk of it. He never complained about his wife, but Loreda knew how he felt, so she complained for him. It brought them closer, proved how alike they were, she and Daddy.

As alike as peas in a pod. Everyone said so.

Like Daddy, Loreda saw how limited life was on a wheat farm in the Texas Panhandle, and she had no intention of becoming like her mother. She was not going to sit on this dying wheat farm for her whole life, withering and wrinkling beneath a sun so hot it melted rubber. She was not going to waste her every prayer on rain. Not a chance.

She was going to travel the world and write about her adventures. Someday she would be as famous as Nellie Bly.

Someday.

She watched a brown field mouse creep along the baseboard under the window. It stopped at the teacher’s desk, sipped at a blot of fallen ink. When it looked up, blue painted its tiny nose.

Loreda elbowed Stella Devereaux, who sat at the desk next to Loreda.

Stella looked up, bleary-eyed from the heat.

Loreda indicated the mouse.

Stella almost smiled.

A bell rang and the mouse ran into the corner and disappeared into its hole.

Loreda got to her feet. Her flour-sack dress felt sticky with sweat. She grabbed her book bag and fell into step with Stella. Usually they’d be talking nonstop on the way out, about boys or books or places they wanted to see or movies coming to the Rialto Theater, but today it was too hot to make the effort.

Loreda’s little brother, Anthony, was the first one to the door, as usual. At seven, Ant ran like an unbroken colt, all bent elbows and loose joints. More spirited than any of the other children, Ant always had a spring in his step. He was dressed in faded, patched dungarees that were inches too short, the ragged hems revealing ankles as skinny as broom handles and shoes with holes in the toes. His freckled, angular face was tanned to the color of saddle leather, with big red patches of sunburn on his cheeks. A cap hid the fact that his black hair was dirty. Outside, he saw his parents in the wagon and waved broadly and started to run. He had never known anything but drought, not really, and so he played and laughed like an ordinary boy. Stella’s younger sister, Sophia, tried gamely to keep up with him.

“How does your mom always sit up so tall in this heat?” Stella said. She was the only kid in class wearing new shoes and a dress made from real gingham. Times weren’t so bad for the Devereaux family, but Loreda’s grandpa said all the banks were in trouble.

“It doesn’t matter how hot it is, she never complains.”

“My mom doesn’t say much, either, but you should hear my sister. Ever since she got married, she cries like a stuck pig about all the work it takes to be a wife.”

“I ain’t getting married,” Loreda said. “My dad and me are going to go to Hollywood together someday.”

“Your mom won’t mind?”

Loreda shrugged. Who knew what bothered her mom? And who cared?

Stella and Sophia turned left and headed toward their home on the other side of town.

Ant ran up to the wagon.

“Hey, Mommy,” Ant said, his grin showing off a new lost tooth. “Daddy.”

“Howdy, son,” Daddy said. “Climb into the back.”

“D’ya wanna see what I drew in class today? Missus Buslik says—”

“Get in the wagon, Anthony,” Daddy said. “I’ll see your artwork at home, when the sun goes down and we are out of this damnable heat.”

Ant’s face fell in disappointment.

Loreda hated how sad and beaten her dad looked. The drought was sucking him dry. He and Loreda were bright stars who needed to shine. He said so all the time. “You wanna go to the movies tomorrow, Daddy?” she said, staring up at him adoringly. “ Little Miss Marker is playing again.”

“There’s no money for that, Loreda,” Mom said. “Climb in the back with your brother.”

“How about—”

“Get in the wagon, Loreda,” Mom said.

Loreda tossed her book bag into the back of the wagon and climbed in. She and Ant sat close together on the dusty old quilt that they kept in the back.

Mom snapped the reins and they were off.

Swaying with the motion of the wagon, Loreda stared out at the dry land. The air smelled of dust and heat. They passed the rotting carcass of a steer, its ribs sticking up, its horns reaching out from the sand. Flies buzzed around it. A crow landed on the carcass, cawed proprietarily, and began plucking at the bones. There was an abandoned Model T beside it, doors open, tires buried up to the axle in dry soil.

To their left stood a small farmhouse, unshaded by trees, surrounded by brown earth. A pair of signs—AUCTION and FORECLOSURE—were hammered to the front door.

In the yard, a jalopy was stuffed to the gills with people and junk. Tied to the back end were a stack of buckets, a cast-iron frying pan, and a wooden crate full of mason jars and sacks of wheat. The running engine puffed black smoke into the air and rattled the metal frame. Pots and pans had been tied wherever there was something to tie them to. Two children stood on the rusty running boards and a woman with a sad face and lanky hair sat in the passenger seat holding a baby.

The farmer—Will Bunting—stood by the driver’s-side door, dressed in coveralls and a shirt with only one sleeve. A banged-up cowboy hat was pulled low over his dusty face.

“Whoa,” Mom said, drawing the gelding to a halt, tilting back her sun hat.

“Heyya, Rafe,” Will said, spitting tobacco into the dirt at his feet. “Elsa.” He pulled away from the overburdened car, walked slowly toward the wagon. When he got there, he stopped, said nothing, shoved his hands in his pockets.

Читать дальше