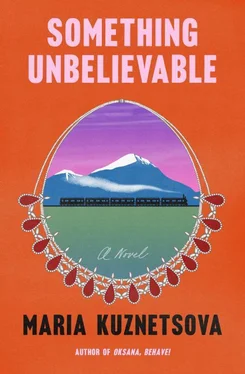

Мария Кузнецова - Something Unbelievable

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Мария Кузнецова - Something Unbelievable» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2021, ISBN: 2021, Издательство: Random House, Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Something Unbelievable

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House

- Жанр:

- Год:2021

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-52551-191-5

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Something Unbelievable: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Something Unbelievable»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Something Unbelievable — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Something Unbelievable», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I wished I were sitting with the more serious, melancholy Misha instead of this rascal with slicked-back hair, who acted like a smug lord looking over the commoners. He had managed to dispel all the goodwill I had sent his way for playing with Yaroslava with this little speech. Besides, his favorite playmate had gotten sick the day before, so perhaps he was just bothering me out of boredom. Aunt Yulia was very worried, but Mama assured her it would pass, that the feverish child was just hungry, though I did not know exactly how it would pass when there seemed to be no hope of better food on the horizon. The girl rested in her parents’ laps, and her hair was damp and matted to her head.

“How do you know all this anyway?” I finally asked.

“I hear Papa talking, that’s how,” he said.

“And does your father—share your perspective?”

“Of course not,” he said. “You think you can learn everything from your books, but the only way to truly know the world is to hear what people are saying.”

“I don’t read to learn,” I said, uncertain as to how the conversation had turned from Stalin to literature. I would often bring novels to our families’ gatherings and would hide off in a corner to escape to my beloved pages. But I did not know Bogdan paid enough attention to see what I was doing.

“Oh?” he said, looking genuinely surprised. “Then why do you do it?”

“I like to read….” I said, realizing I did not have a good answer. I knew it had something to do with making me feel less lonely, to connect me to lost souls from generations ago, many of whom came from the same place, but this was difficult and embarrassing to articulate. I said, “Because language is beautiful, even when it’s ugly.”

If Bogdan expected me to say more on the subject, then he would be sorely disappointed. I could not entertain him the way the little girl had, and I wasn’t one of the neighborhood boys who called him outside to engage in mischief whenever my family visited. This was the longest conversation we had ever had. Until then, our talk had been limited to asking each other to pass the potatoes. He always had that look about him, of a person on the hunt for something more exciting to do, but for once he was calm, perhaps because there was nowhere to go.

I turned away, toward the window, where the vast fields were illuminated by a bright, nearly full moon. I had hardly been staring out for a moment before he pulled me toward him and shielded my eyes. I was so stunned by the gesture—we had not done so much as shake hands until then—that I stayed there instead of protesting. I did not know if I wanted to be held or to see. If the thing he shielded me from was so awful that it warranted shielding. I could feel his heart beating against my cheek. When he released me, the fields were as vacant as ever.

“What on Earth was that?” I said.

“Nothing,” said Bogdan, but I could see he was ruffled, that his jaw was set and he was struggling to maintain composure. “Just a few dead cows. Starvation. It was very unpleasant.”

“That’s all?” I said. I most certainly did not believe him. Or, I mostly did not. Or perhaps I wanted to believe him so badly that I decided to. A few dead cows did not a tragedy make.

“That’s all,” he said, giving my arm a squeeze, not looking me directly in the eyes either. Had he looked me in the eyes to begin with? It was hard to say.

“We’re the same age, you know. I don’t need protecting. I’m not a child.”

“I never said you were,” he said, and he was quiet after that. I stared out at the vast emptiness, where I could detect no farms, which made the likelihood of dead cows quite low. Bogdan did not leave me, either because he felt I needed further comfort or because he did not want to be alone after spotting whatever dark thing had been lurking outside.

Soon enough my savior was asleep, tilting his head closer and closer toward mine until he collapsed on my shoulder. I did not move, wanting to shake him off but also not wanting him to wake up finding himself in this compromised position, so I sat there, rigid as a lamppost. From that angle, one that allowed me only to see his thick, haphazard hair and the top of his head, he was once again indistinguishable from his brother. So that was what I did then, I pretended Misha was resting his head on my shoulder and closed my eyes and leaned my head against his, at last settling into something resembling sleep.

Misha and I were reading The Idiot when the book began to quiver in my hand, and then the train shook violently. A siren rang through the cars and the train came to a halt, pitching us into the wall. Papa grabbed Polya and Baba Tonya’s hands and Mama grabbed mine, everyone was grabbing everyone and the Orlovs and Garanins were shouting, too, come on, let’s go, hurry up, hurry up, get off this train, take nothing with you, and even in the chaos it registered that there were explosions overhead coming from the formerly empty sky, making me question why exactly we were leaving.

“Come on, now, quickly, girl,” said Mama, and we jumped out of the wagon and crawled right under the train, hid down in the warm darkness, scared white pupils blinking in the blackness, reminding me of the eyes of Timofey lighting up our courtyard as the dawn broke.

It was the Germans, of course. I did not need Papa to confirm this, though he did, or to explain to the group that though it may seem ridiculous to stay right under the train when the bombs were falling down on it, it was the safest place for all of us to be, since it was our only shelter in the vast steppe and the steel of the trains over our heads would provide more protection than the open fields could. We crouched in the muck, covering our ears; the Orlovs were silent and dignified while Polya and my grandmother whimpered. The old woman’s boa was filthy and she looked so ridiculous that I wanted to choke her with it, or even to rip off her rubies and toss them out from under the train so she would get bombed while running after them. I was so terrified that it took me a moment to see that Papa was not beside us, that he had rushed into the fields to bring back a few rogue passengers who fled the train.

“Get back here, Fedya!” Mama screamed, but the sounds of the crashing bombs were so loud that I doubted if anyone heard her but me. But it was instinctual with Papa. He saw people who needed saving, so he went out to save them, forgetting that he had a family waiting for him under the train. Mama muttered that his orphanage instincts were kicking in again, this flagrant caring for others. But I was just glad he had returned to us.

Polya was crying and Baba Tonya was crying and Mama was comforting them both, while Papa met my gaze and nodded.

“My big girl,” he said. “My stalwart.”

“Let them just take me now,” Baba was muttering. “Let this be it. Haven’t I suffered enough?”

It got wearying after a while, though, the bombs, the hands on the ears, the thighs burning from all the crouching, the gravel and dirt digging into my knees, the hunger weakening my joints, the foul stench of the unbathed passengers. I opened my eyes and saw that Bogdan the rascal had stopped the assumed crouching position and even looked quite jolly for some reason, which turned out to be because little Yaroslava, who had not only grown weaker in recent days but who had also begun to chatter her teeth and look alarmingly pale, was looking at him with a trembling expression somewhere on the brink of bursting into sobs or hysterical laughter. Her golden pigtails mingled with the muddy ground.

Bogdan was amusing her by making a monkey face, and he reached into his pockets and pulled out two tiny teacups he must have stolen after a tea service and put them to his eyes and bobbed his head from side to side and stuck out his tongue. This image was so absurd, what with everyone else crouching and the bombs dropping from overhead planes, the sound of them raining down on our only mode of conveyance, that even I had to hold back a chuckle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Something Unbelievable»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Something Unbelievable» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Something Unbelievable» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.